Independent reading

Image credit: Photo by Pierre Bamin. Unsplash. License to use.

Giving students time to read a book of their choice during the school day, for pleasure, is one of the most effective ways to build a reading habit.

Why independent reading matters

Reading independently boosts reading mileage, vocabulary and comprehension. It also:

develops cognitive stamina

helps with wellbeing

opens doors to new ways of thinking and living.

Time for independent reading during the school day is not a new concept. The term ‘Uninterrupted Sustained Silent Reading’ (USSR) was introduced in 1960.

Other independent reading programmes include:

Sustained Silent Reading (SSR)

Drop Everything and Read (DEAR)

Daily Independent Reading Time (DIRT)

Everybody Reading in Class (ERIC).

Regardless of the title, the programmes all allow time for students to read books they’ve chosen, silently and without interruption. Some schools have a set time every day, for example, for 15 minutes after lunch. Regularity helps build the reading habit.

Staff are important reading role models and it’s powerful when they also use this time to read.

What the research says

Stephen Krashen’s research in the Power of Reading (2004) compared schools that used in-school free reading programmes with those that only focused on traditional, skill-based reading instruction. It found:

in 51 out of 54 comparisons (94%), students did as well or better in reading tests

the longer an in-school free reading programme ran, the more consistent the reading comprehension results.

In Free Voluntary Reading, Stephen Krashen states:

The evidence is overwhelming that reading for pleasure—that is, self-selected recreational reading—is the major source of our ability to read, to write with an acceptable writing style, to develop vocabulary and spelling abilities, and to handle complex grammatical constructions. The evidence holds both for English as a first language and for English as a second and foreign language.

— Stephen Krashen (2021), Free Voluntary Reading

Understanding the value of independent reading

Margaret Merga researched perceptions of the value of reading. Teachers reported their students benefited from a well-set-up, independent reading programme. These programmes developed skills, increased engagement and improved wellbeing. She also found the following:

Not all children understand that reading is important beyond learning how to do it. So, they do not place value on making time for independent reading.

Educators and parents need to present reading as an important and enjoyable recreational activity, with immediate and future benefits.

There is a need to shift some children’s beliefs that ‘some people are good readers, and some people aren’t’.

Children’s perceptions of the importance and value of reading — Margaret Merga and Saiyidi Mat Roni, 2018.

Teachers’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of a whole-school reading for pleasure program – Margaret Merga et al, 2021.

Most effective when part of a reading programme

Research that questions the success of independent reading tends to analyse it as a stand-alone practice. However, most evidence shows it does help when part of an effective reading programme.

A systematic review of 14 studies released in 2021 by Erbeli and Rice reported inconclusive findings. But they identified that independent reading:

needed to be one of many strategies used in the classroom for it to be a practical way to improve reading outcomes

had the strongest benefits amongst older students when decoding skills were already acquired.

Examining the effects of silent independent reading on reading outcomes

Taking a school-wide approach

Independent reading has the most chance of success when school leaders support a whole-school approach. When practised for pleasure across the school, it becomes an effective element within the whole-school reading culture.

Ideally, students read for pleasure at home as well as at school. However, not all students have access to:

a range of appealing books

people who can help them choose or suggest books

time (or prioritising time) to read

supportive environments that encourage reading for pleasure over other expectations or commitments.

First and foremost, schools need to provide class time for silent reading for pleasure, and not assume that teenagers have the time, resources or inclination to do this at home. If teachers model positive attitudes toward reading, promote the ongoing importance of reading, and give students a chance to build the cognitive stamina needed to read deeply, we can increase the chance of students choosing to read beyond school.

— Margaret Merga (2022), How to encourage teens to read

See how Queenwood School for Girls in Sydney began their project Just Read to increase reading for enjoyment across the school: The time to read.

Effective strategies

Several factors are regularly referenced as supporting an effective independent reading programme. There's no guarantee they will work all the time, every time, and for every student. But any teacher wanting to build independent reading into their programme should keep these in mind.

Give it time

Time to:

develop and design a vision based on increasing student’s enjoyment of reading and/or the social capital of reading

bring staff on board through relevant and practical professional development

develop and refine strategies and practices so that they are consistent — this may include gathering staff and student voice

embed the programme so it adds value within the culture of the school.

After a year of engaged independent reading, students shifted from viewing reading as isolated and accuracy focused to viewing it as an opportunity to make meaning. The findings suggest that fears about emergent readers being unable to productively use independent reading time may be unfounded.

— Lindsey Moses and Laura Beth Kelly (2019), Are they really reading? A descriptive study of first graders during independent reading

Role model reading

Here are some suggested ways you can role model:

Read during independent reading time. You may need to start small and work up to longer periods of reading.

Share and book talk — about how you select books, the book you are reading, your reading identity.

Show a positive attitude. Be enthusiastic and show an interest in books and reading, regardless of the age you teach or your subject. Seeing your enthusiasm will help students become enthusiastic too.

Make sure students can access reading material

Students need ready access to material and choice to encourage reading.

Provide a wide selection of reading material to ensure everyone can find something to engage with. Do they have access to graphic novels, magazines, quick reads, series, non-fiction, picture books, poetry? Does your school request loans from the National Library for extra books?

Keep encouraging students to try new or a variety of books. Are you rotating collections? Allow students time to share books with each other. Ask for their suggestions.

Guide them on how to select books, providing skills, strategies and time to choose.

Encourage students to recommend books to others. Allow time for them to talk with peers, teachers, librarians, authors. Do you provide or source book lists or gateway books?

Self-selected reading is vital. Provide time for students to choose books. Talk to students about how we read and our rights to read. Remind them that they have the agency to choose what they read. For example, it’s okay for them to choose an easy read, re-read a favourite, give up on a book.

Helping students choose books to read for pleasure

Books and Reads — for kids and teens

Provide great reading environments

Students need routines and a place to read.

Establish routines. When do you provide time for selection, independent reading, sharing? What are the expectations?

Make sure students have a space that encourages reading for pleasure. Are students allowed to choose where to sit, are they guaranteed uninterrupted reading time, do they have access to books?

In school and at home, students’ lives are full of competing priorities. If we want them to value and appreciate reading as a worthwhile pursuit, then we need to be explicit about the benefits.

We need to show students that we prioritise it by giving it the time and space it deserves within our school timetable.

So, where we can provide that opportunity for deep and sustained reading in a school context, not only are we providing students opportunity to be exposed to vocabulary, to build their reading comprehension, we’re also communicating to young people that it’s something that’s valuable enough to give valuable time up from the curriculum to devote to the practice.

— Margaret Merga (2019) The Research Files Episode 53: Building a school reading culture

Find out more

The Open University Reading for Pleasure: Independent Reading — research, classroom strategies, podcast, resources.

Cuevas, J., Irving, M. & Russell, L. (2014). Applied cognition: Testing the effects of independent silent reading on secondary students’ achievement and attribution. Reading Psychology, 35 (2), 127–159.

Krashen, S. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Libraries Unlimited, Heinemann.

Mace, G, & Lean, M. (2021). Building a reader for life: A sustained silent reading programme for K-11 — Just Read. Access, 35 (1), 32–39.

Van Rij, J. (2018). Reading matters: One school’s journey back to SSR. English in Aotearoa, 93, 30–32.

Related content

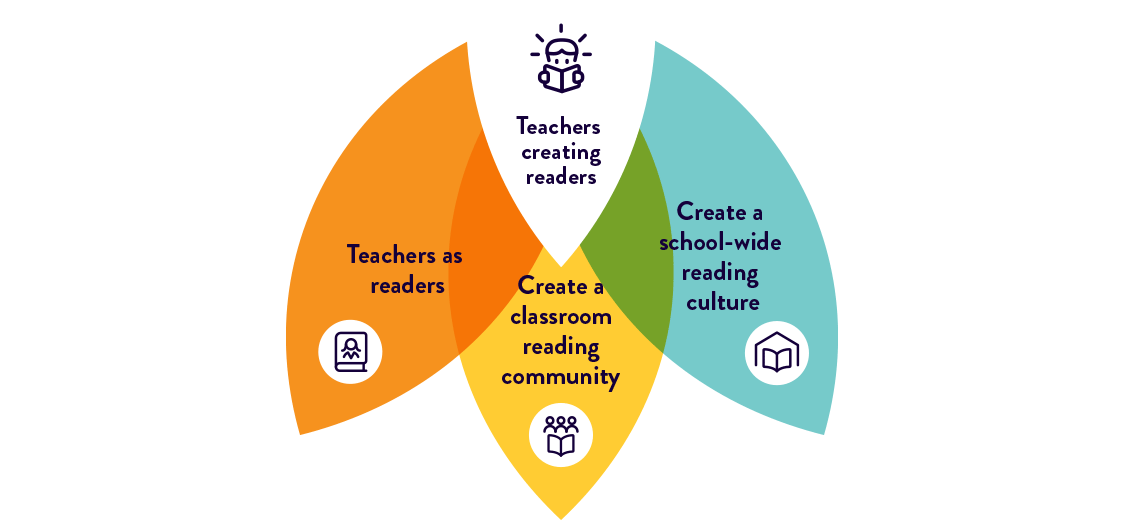

Teachers Creating Readers Framework and examples of practice

Teachers create readers by being reading role models and knowing strategies that inspire and support reading for pleasure. Explore our Teachers Creating Readers Framework and examples of practice. Use our booklet, posters or tool for inspiration and ideas.

Understanding reading engagement

Find out what reading engagement is and why it matters. Explore ideas, strategies, and research for engaging students with reading by creating a community-wide culture that supports reading for pleasure.