Supporting inquiry learning in kura kaupapa Māori

All rights reserved

This case study shows a process for guiding ākonga (students) through inquiry learning in kura kaupapa Māori.

Follow the journey, use the resources

The ākonga learn how to:

locate relevant information and ideas

evaluate and make sense of that information

integrate information and ideas within and across a range of texts

think creatively, and transfer and apply their knowledge and skills in new contexts to deepen their learning.

Follow the kura's learning journey, or use the teaching resources they created, with your own ākonga.

He pakirehua i roto i te kura Māori — a model of inquiry learning in kura Māori

Inquiry learning is most effective when it involves the whole kura, including the library. Many models of inquiry learning exist — each follows a cycle of discovery for deeper understanding.

Understanding inquiry learning gives some models and approaches for inquiry learning.

6 kura worked together to develop this model

With the support of the University of Auckland Faculty of Education and National Library Services to Schools, 6 kura kaupapa Māori from the Tamaki Makaurau Rumaki ICT Cluster worked to embed inquiry learning into their practice. The kura involved were:

- Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Puau te Moananui a Kiwa

- Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Ngā Maungarongo

- Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Te Raki Paewhenua

- Te Wharekura o Manurewa

- Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Te Puaha o Waikato

- Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Mangere.

Teachers from each kura:

- completed professional development about inquiry learning with the University of Auckland and National Library Services to Schools

- collaborated to develop a model of inquiry learning for kura kaupapa Māori

- carried out inquiry units on the theme: 'tō tātou wāhi'.

Stages of inquiry

The inquiry model developed by the teachers involved had the following stages:

- Initiate the inquiry process

- Stage 1: Whakatau — deciding: key concept, pre-teaching, brainstorming, mapping, keywords, key questions, planning

- Stage 2: Rapu — finding: print and online searching, using authentic learning contexts

- Stages 3 and 4: Whakamahi and whakatakoto — using, analysing, organising, synthesising

- Stage 5: Whakaatu — presenting

- Stage 6: Aromātai — evaluating.

In the following sections, the teachers outline their journey and share resources they created to help teachers and ākonga with inquiry learning.

Initiate the inquiry process

Planning for inquiry

The following planning tools were developed for the teachers:

Te pakirehua / Inquiry unit plan template (docx, 223KB) — for teachers to plan inquiry units.

Year 9 inquiry unit plan example (pdf, 302KB) — a completed inquiry unit plan for a year 9 class.

Kura information literacy continuum (pdf, 300KB) — the information literacy skills ākonga should be learning at each inquiry stage and at each level.

Papakupu mō te huarahi pakirehua / Glossary for inquiry learning (pdf, 319KB) — a glossary of Māori terms for the inquiry process.

Introducing the inquiry process to ākonga

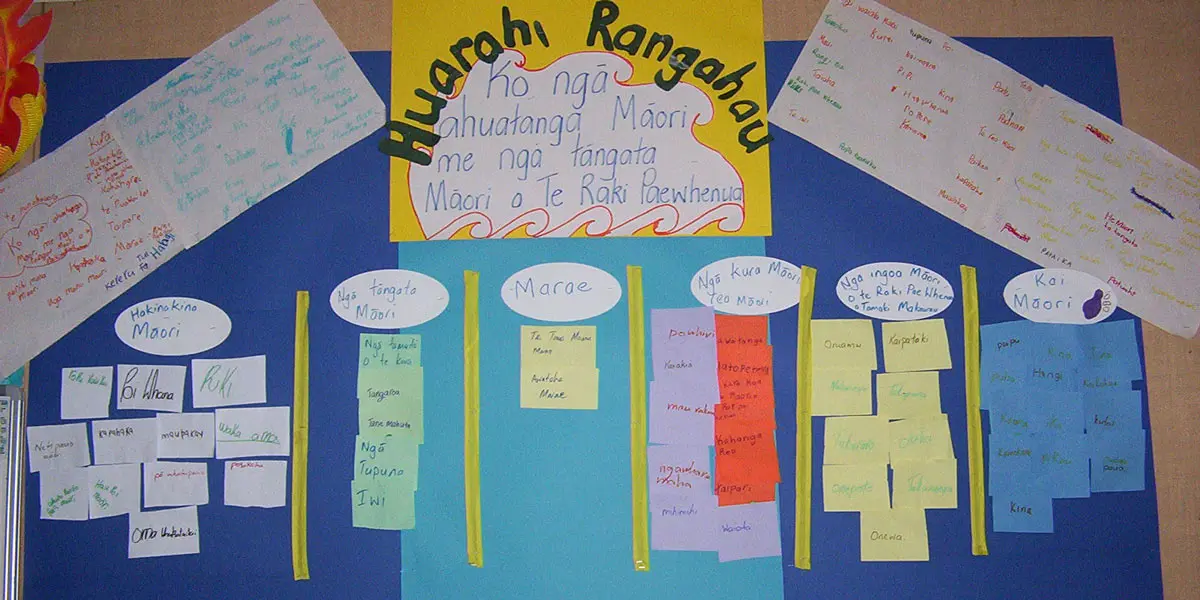

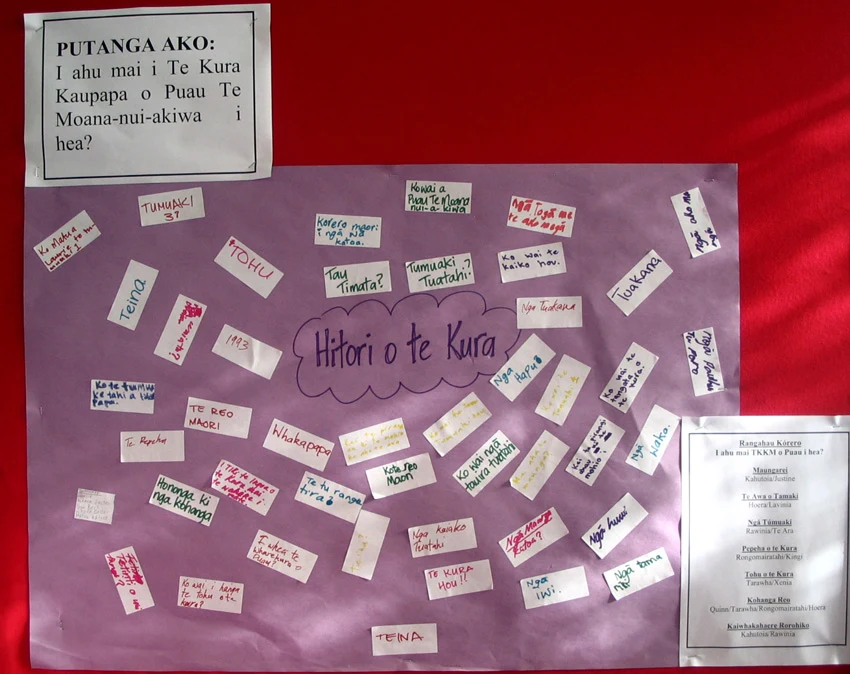

It's important to provide an overview of the inquiry process to the ākonga so they understand it and can see all the different stages. One way of doing this is to create a visual wall display.

Some teachers used the wall display as a monitor for their ākonga. The ākonga moved their names along as they progressed through the stages.

Stage 1: Whakatau — deciding

Āria matua — key concept

An āria matua / key concept connects the ākonga to why the topic is important to learn about.

For example: 'Mena kāhore tātou e ako ana ki te hangarua ka kīkī haere ngā wāhi rāpihi.'

Mahi whakarite — pre-teaching

In order for ākonga to engage and ask questions about a kaupapa, they first need some basic knowledge about it. A kaiako (teacher) can provide ākonga with some facts/concepts/understandings so that they can engage more effectively in brainstorming.

Ohia manomano — brainstorming

Ākonga brainstorm general ideas about the kaupapa before they engage with inquiry learning in depth.

Pakirehua ture ohia manomano (pdf, 224KB — use this guide to find out what the ākonga already know.

I used brainstorming in our writing time. The children talked about weekend mahi and then we brainstormed one as a tauira. Children continued with individual brainstorms in their books then wrote stories. We also practised brainstorming whakaaro about non-fiction books that each group had.

— Sarah Pickering

Mahi mahere — mapping

Mapping sorts your brainstormed words into groups/whānau or categories. This can help clarify thinking about the āria matua.

Kupu matua — keywords

Select kupu matua / keywords. Keywords are the most important words or terms used to search the library catalogue, internet, or index and contents pages in books to find information about the inquiry topic.

We selected the words from the brainstorm and mind maps. Then the ākonga highlighted the keywords they decided on. We practised looking up these words in the school library catalogue and internet and on the contents and index pages of the books they had in their classroom. They had to rethink some of the words as it wasn’t always possible to find the information we were looking for using those words.

— Gwendoleine Taare

In this year 1 and 2 class, kupu matua were displayed on the wall

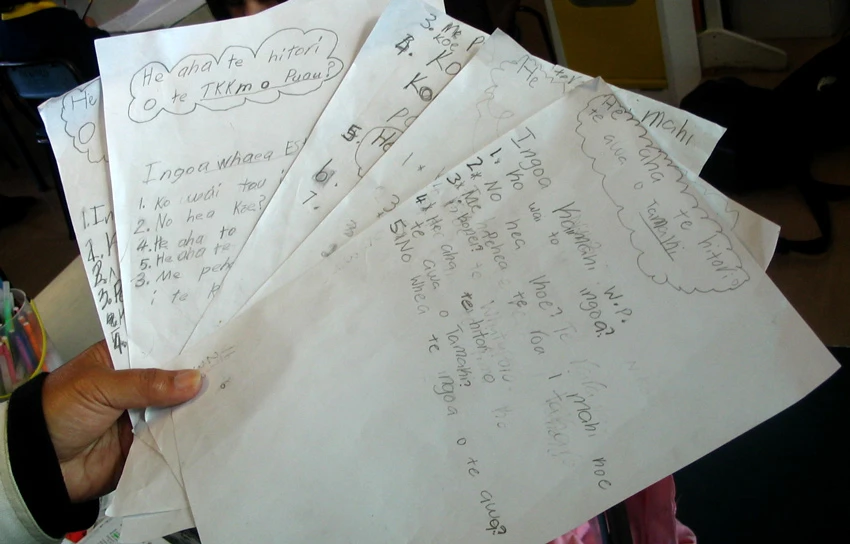

Pātai matua — key questions

Use the keywords to form pātai matua / key questions. Key questions need to be open-ended and range from factual, simple questions that can be answered easily to powerful, fertile questions that are more complex. Ākonga need to be taught how to ask good questions.

I used the keywords to model framing a question, with the question-starters we had used with picture sets: kei hea, he aha, he aha ai, ko wai, āhea, ināhea. We spread out 2 sets of words on the floor: the question-starters and keywords. Children then chose the keyword and a question starter to give something tangible for them to look at, hold, and write to.

— Marieanne Selkirk

I introduced the tamariki to questioning skills during morning talk sessions. The tamariki could all ask questions but quite often they were not relevant or correct. So we focused on basic questions to extract more information e.g. Ko wai? E hia? He aha ai?

— Marama Tuuta

Whakariterite — planning

Ākonga plan:

where they will go for resources or sources of information

how they will present their new knowledge

who they will present it to (the audience), and

the time it will take to complete the different stages.

Read these examples:

Pakirehua — mahere whakatau (docx, 670KB) — planning inquiry template for ākonga that was used with a year 1/2 class.

Kura tuatahi inquiry planning template (pdf, 240KB) — used with year 3 and 4 ākonga.

Stage 2: Rapu — finding

This stage involves gathering information from different sources and resources and/or making discoveries through exploration.

Printed resources

Before starting, we learned about the whare pukapuka. I showed the children the Dewey chart in Māori. We then played games such as 'kei hea ngā pukapuka e pā ana ki te whana poikiri'.

— Sarah Pickering

I mixed up the books I had found on kites with other non-related books. On an A3 green sheet, I wrote 'Kei te pai'. On the red sheet, I wrote 'Kāhore i te pai.' I wrote on the board our keywords (Māori and Pākehā) Manu aute / kites, build, hanga, make, mahi, fly, flying, rere. We discussed that we were looking for books that could help us build a kite. By using the keywords, we would select the relevant books. The tamariki looked at the books and then I asked them to place the books we needed onto the correct paper.

— Marama Tuuta

Rauemi ipurangi — online resources

When using online, digital resources, it's important to teach your ākonga strategies to find te reo Māori websites. For example, use websites or portals such as TKI (Te Kete Ipurangi) and Te Ara which you can search using Māori keywords and will return te reo Māori information (if available).

Resources to help ākonga search for resources online include:

Search strategies on the internet (pdf, 281KB) — a worksheet created to help year 9 ākonga develop their internet search skills, based on their inquiry on volcanoes.

Digital content — finding, evaluating, using and creating it — explores a range of strategies to develop digital literacy skills that support inquiry learning.

Authentic learning contexts

Te Wharekura o Manurewa year 9 class was doing an inquiry unit on tuna. Their finding stage involved a field trip where they made their own tuna net, got their own bait, set the net, and caught their own tuna.

Ākonga at Te Wharekura o Manurewa making a hinaki and catching tuna (eels). All rights reserved.

Local experts and kaumātua

Depending on the inquiry topic, interviewing local experts and kaumātua can be a rich resource for ākonga to enhance their learning and understanding. Your school library can gather and store the contact information for local experts and kaumātua who can assist with inquiry learning topics.

Stages 3 and 4: Whakamahi/whakatakoto — using/ analysing/organising/synthesising

These stages focus on how the information collected is used to answer the questions and develop understandings.

Skimming and scanning English texts using keywords

Often a difficulty for kura is finding print and online resources in te reo Māori. Use some of these strategies:

Ākonga skimming for keywords in both languages — the teacher can then translate orally the sentence in which the keywords had appeared.

Getting parents to read the information aloud in English to ākonga at home. "The tamariki took reading home to matua to read to them. When the tamariki returned to kura, we discussed ngā whakautu i roto i te reo Māori" — Sarah Pickering.

Note-taking worksheet (docx, 233KB) — a teacher translated a piece of text and then set up a note-taking sheet for ākonga to first extract keywords and then form their own sentences.

Note-taking skills using the dot and jot method (pdf, 246KB) — for older ākonga, using the dot and jot method teaches them to take notes from several sources before combining the information to form their own understandings. If taught consistently, it will stop blanket copying and pasting. An important strategy for teaching all these skills is for the teacher to model first, for example by modelling video note-taking.

Note-taking/recording strategies

Prior to the unit, I integrated note-taking strategies into the daily programme across all marau so they could transfer skills. I would lead the tamariki and they would write out lists of keywords and key phrases. They would read their own paragraphs and then circle keywords. After this, they wrote in their own words their whakaaro e pā ana ngā kupu kī.

— Sarah Pickering

Visual recording

For younger ākonga, visual images are an important way to record information.

Most tamariki used pictures to record information about their topic as they were dependent on the teacher for reading and writing. I would also read books aloud to the whole class who would record keywords.

— Hinemoa Hunziker

Organising information

Teaching the ākonga to organise their information is also an important skill.

The tamariki all had a folder in which they stored their information they gathered. They found pages in books they wanted photocopied, used post-its to mark these pages, and then photocopied them themselves.

— Hinemoa Hunziker

Stage 5: Whakaatu — presenting

Ākonga need to know how to present their new findings and understandings. A shared presentation is more powerful than a submitted essay, and ākonga can learn from each other’s presentations.

We practised, in our reading programme, plays from journals to reinforce their communication skills. It taught the children confidence, voice projection, and gestures. They also practised walking while giving morning korero, using hands, speaking clearly, and focusing on an audience.

— Sarah Pickering

Year 9 ākonga from Te Wharekura o Manurewa used PowerPoint to present their inquiry learning on tikanga and methods of catching tuna.

Stage 6: Aromātai — evaluate

The inquiry process and skills used can be evaluated as well as the final product.

Checkpoints are a method of formative assessment, a way of monitoring the research process and the ākonga’s progress, including checking if they need more scaffolding or teaching of specific skills.

The following resources were used by teachers:

Self-assessment: Te reo (docx, 156KB) — used with year 1 and 2 ākonga to document each stage and activity for them to assess themselves as they completed it.

Te aromatai (docx, 232KB) — teacher’s evaluation of each ākonga’s progress through the whole inquiry learning process.

This was completed during group conferencing sessions, which involved oral reflections on what worked well and what could be done better next time.

— Hinemoa Hunziker

Aromatawai — assess

The following rubrics were developed to assess product and/or process:

Teacher reflections

The biggest challenge for teachers in kura is the lack of print and online resources in te reo Māori.

A couple of strategies have already been outlined (see 'Stage 2: Rapu — finding') about how to use English resources. Other possible solutions include:

only selecting inquiry topics that have print and online resources available in te reo

selecting an inquiry unit using people as your sources of information

carrying out authentic learning experiences, like Te Wharekura o Manurewa did with their inquiry on tuna.

Many kura have their own libraries. It's important that the library catalogue system is set up to enable the ākonga to search in both te reo Māori and English.

If Ministry of Education resources, such as Te Wharekura, are also catalogued on the library system, this will also greatly improve access to these resources (often the only ones available on a topic in Māori) for ākonga and teachers.

Te Kete Ipurangi (TKI) — searchable in te reo Māori.

Te Ara — te reo Māori version.

Resources supporting inquiry learning in kura kaupapa Māori

The National Library and Services to Schools provide search functions and a range of quality, free resources that can be used to support inquiry learning in kura kaupapa Māori, including:

Topic Explorer — Te reo Māori — resources to support you when you need information relating to the topic, te reo Māori.

Papers Past — newspapers in te reo Māori and Te Ao Hou magazine, which has articles in te reo Māori.

Index New Zealand — find abstracts for te reo Māori articles. Abstracts are written in both te reo Māori and English.

Ngā Upoko Tukutuku — use this tool to search the National Library collections on topics using Māori concepts familiar to your students.

Iwi Hapū Names List — search our collections using standardised iwi and hapū terms.

DigitalNZ — online resources that can be searched by subject and the results easily curated for future reference.

EPIC — access a wide range of quality, online resources.