Books in world languages

Books in world languages help reinforce a sense of identity. Having them for students to enjoy, allows you to build a culture of inclusion and acceptance. Read how to support a collection in your class or school library and use the books to engage readers.

World languages books in Aotearoa New Zealand

World languages books in Aotearoa New Zealand refer to books written in a language other than English or te reo Māori.

These books can support speakers of other languages (ESOL). They could also be useful for anyone interested in or learning another language.

Why have books in world languages?

Aotearoa New Zealand is a diverse country with over 200 ethnic groups who speak 160 languages. Research shows significant benefits for students remaining fluent in their home language. Accessible texts allow students to connect and remain connected with their first language and culture. They reinforce a sense of identity and provide opportunities to teach inclusivity and appreciation of diversity.

Reading in their home language:

enables students to read for pleasure in that language

provides a strong foundation for learning another language

strengthens bonds to family and community

helps develop a positive sense of identity.

Extending their language — expanding their world — New Zealand research from Education Review Office.

Why is it important to maintain the native language? — article from the Intercultural Development Research Association.

Mirrors and windows in our library collections — post on our Create Readers blog.

Other names for books in world languages

There are various terms used for books in world languages such as:

native language

mother tongue

heritage language

home language

heart language

first language.

Whatever you choose to call them, make sure these books are accessible and celebrated as a valuable resource.

The South Dunedin Communities of Readers project, Read Share Grow (a National Library initiative) selects and supplies diverse books in ‘home and heart’ languages to reflect the community.

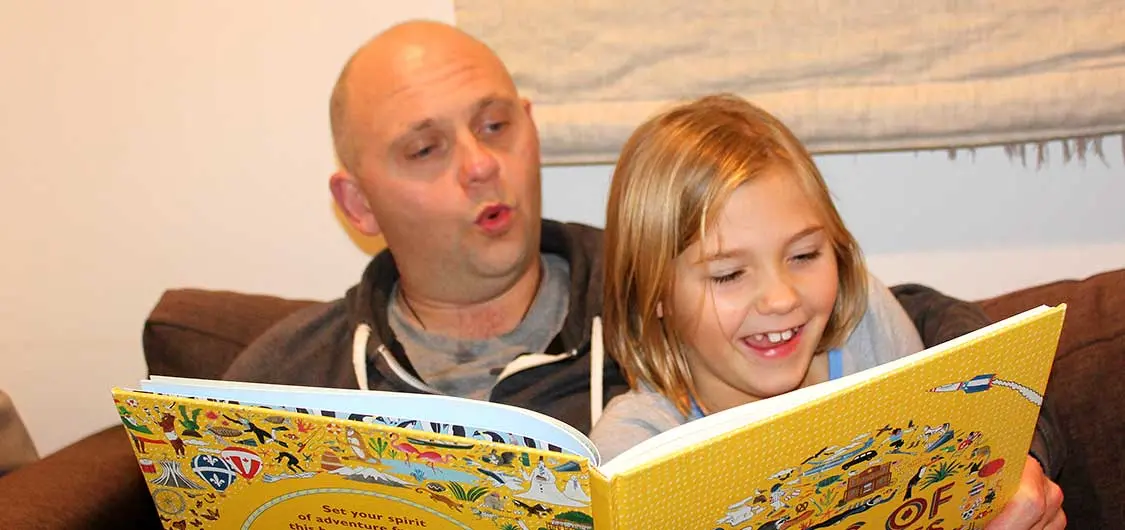

… the early evidence suggests that many of the books are going to families with few or no children’s books at home. There is also emerging evidence that the right books, in the right places, at the right time, in home and heart languages is having an impact on shared reading. All the families who had received books said they had read them to their children and that both they and their children were enjoying them, particularly if the children had been able to choose the book themselves.

— Alex Woodley, ‘Insights report — Community Project’

Pūtoi Rito Communities of Readers Phase 1: 2019 – 2021 summary and insights report

Making books in world languages available to students

Borrow through our lending service

Use our school lending service to borrow picture books, fiction and some high-interest non-fiction books from National Library's World Language collection.

Books in our lending collections for schools — find out more about books in our lending collection, including those in world languages.

More about our lending service for schools and home educators

Create a classroom or library collection

The books may be in a language you cannot speak or understand. Build a support network to help you choose the best books for your students. Use the resources you have, for example:

draw on the expertise of parents, members of your community and local librarians

request loans from the National Library to help gauge student engagement

use translation options (if provided) on eBook platforms.

Using world languages books in your library or classroom

Have a range of fiction and non-fiction available.

Encourage students to take the books home to read for pleasure on their own or share with whānau.

Provide time for students to read for pleasure.

Create opportunities for book chat with others in the class. Even with limited English, students can share their favourite pages, characters or pictures. Encourage them to also bring books in from home.

Invite parents who speak another language to class or the library to share their favourite childhood stories and memories associated with them.

Engage the class in exploring the books — what do I see, think, wonder?

Encourage students to create bilingual resources for the classroom or library together. This may help break down communication barriers. Trying out online translation tools may also create a few laughs!

Once the habit has been formed, a student who reads for pleasure in their first language may be more inclined to read for pleasure in any subsequent language they become fluent in.

— Krashen (2004)

Find out more

Heritage languages in schools: A story of identity, belonging and loss — MindShift.

South Dunedin Communities of Readers Project report — National Library of New Zealand initiative to engage children and their families with reading for pleasure and wellbeing.

Supporting multilingualism in the classroom — a webinar explaining why heritage language development is important and how school literacy practices can be adapted to include multilingualism (begin at 28:14 for the role of schools). From the United Kingdom Literacy Association (UKLA).

The joy of having a book in your own language: Home language books in a refugee education centre — Daly & Limbrick, 2020.

Krashen, S. (2004). The Power of Reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann and Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Related content

Understanding reading engagement

Find out what reading engagement is and why it matters. Explore ideas, strategies, and research for engaging students with reading by creating a community-wide culture that supports reading for pleasure.

Building an inclusive collection

An inclusive library collection reflects the diversity of your school in ways that support teaching and learning.