He Tohu: A declaration, a treaty, a petition

Explore the activities in this workbook to guide you through the 3 documents in He Tohu — He Whakaputanga, Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Women’s Suffrage Petition. Download and print the workbook or read the accessible version.

Workbook formats — print or accessible version

Download or print the workbook: He Tohu: A declaration, a treaty, a petition (pdf, 3.83MB).

This page provides an accessible version.

Ka tuia te rangi i runga nei.

Ka tuia te papa i raro.

Ka tuia te maunga whakahī e karapoti nei.

Ko Te Ahumairangi.

Ahu atu ana ki te awa o Tiakiwai.

Nau mai, haere mai ki Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa.

Tēnei whare e whakaahuru nei.

I ngā taonga a kui mā, a koro mā.

Aupiki mai ki te whakaaturanga o He Tohu.

Areare mai ōu taringa ki wēnei kōrero.

Hei arataki i a koutou.

Nō reira.

E ngā mana. E ngā reo.

Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa.

Bound to the sky above.

Bound to the earth.

Bound to the mountain that stands proudly.

Te Ahumairangi.

And the waters of Tiakiwai that extend out before us.

Welcome to the National Library of New Zealand.

This safe place that stands as guardian.

For the taonga housed within left by our forefathers.

Ascend to the place where He Tohu lives.

Let your ears receive these words.

A guide for you all.

Therefore.

All authorities, all voices (all people).

We greet you.

Nau mai, haere mai, tamariki mā | Welcome everyone!

This booklet will guide you through a basic understanding of the 3 documents in He Tohu — He Whakaputanga, Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Women’s Suffrage Petition — so that you can be a clued-up citizen of Aotearoa New Zealand.

The activities will help you develop your knowledge and your own thoughts and feelings about Aotearoa New Zealand’s past, present and future. The vision of He Tohu is ‘He whakapapa kōrero. He whenua kura’, which means ‘talking about the past to create a better future’. That's what this exhibition is all about — understanding our history and empowering you to create a positive future for Aotearoa New Zealand. We hope you might be inspired to use your voice to speak up against injustices and inequalities. You too can be a change-maker and an active citizen!

As the kaipupuri (caretakers) of these important documents, the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa and Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga welcome you to join us on this learning journey.

If you don’t know what a word means, check out the useful glossary, or for Māori words unknown to you, type them into the Māori dictionary online.

Ko wai ahau? | Who am I?

Let’s begin our journey by taking a moment to think about yourself and your whānau.

A pepeha usually includes a special mountain, river or other natural place that a person feels connected to.

Choose one of the 2 templates to complete.

Tōku pepeha

Ko … te waka

Ko … te maunga

Ko … te awa

Ko … te marae

Ko … te iwi

Ko … te hapū

Ko … tōku ingoa

My pepeha

This pepeha template is inclusive of tauiwi, which means non-Māori or those from afar.

Ko … te maunga e rū nei taku ngākau (is the mountain that speaks to my heart)

Ko … te awa e mahea nei aku māharahara (is the river that alleviates my worries)

Nō … ahau (I am from)

Ko … tōku ingoa (My name is)

E mihi ana ki ngā tohu o nehe, o … (I recognise the ancestral spiritual landmarks of) e noho nei au (where I live)

Nō reira, tēnā koutou katoa (Thus, my acknowledgements to you all)

I mōhio rānei koe? | Did you know?

Sometimes our surname can help uncover things about our family history.

Where does your family name come from?

Who could you ask to find out more about your name?

Does your name have a special meaning?

Is there a story related to your name?

You may like to ask a family member about where your ancestors came from, and what places they feel a close connection with.

He Whakaputanga — the Declaration of Independence

He aha te Whakaputanga? | What is the Declaration?

The earliest document in He Tohu, He Whakaputanga — the Declaration of Independence, may be small in size, but it is hugely important. It was how rangatira (Māori leaders) told the world, back in 1835, that New Zealand was an independent Māori nation.

This document’s full name is He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Niu Tīreni. It is the Māori Declaration of Independence. The 52 rangatira who signed it called themselves Te Whakaminenga o ngā Hapū o Niu Tireni, the United Tribes of New Zealand. In the declaration, rangatira, who were concerned about the increase in foreigners coming to Aotearoa, told the world that they had ‘ko te kīngitanga ko te mana’ (sovereign power and authority) here in New Zealand. The British Government officially recognised this declaration.

The English draft of the declaration was written by the British Resident James Busby and then translated into Māori by the missionary Henry Williams. They wanted to help Māori stop Frenchman Charles de Thierry from setting up a colony in the Hokianga. He Whakaputanga is a bold declaration of indigenous power.

I mōhio rānei koe? | Did you know?

He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi both relate to sovereignty. Having sovereignty means that you have supreme power or authority. In other words, you are in charge. It means you are the boss in your country! So, He Whakaputanga sent a clear message to the rest of the world that no one could come to Aotearoa and try to take over.

Did you know that the Māori text was handwritten by a teenager? His name was Eruera Pare Hongi.

From left to right: James Busby, Te Hāpuku, Eruera Pare Hongi, Hōne Heke and Tāmati Wāka Nene.

He aha ōna kōrero? | What does it say?

He Whakaputanga has 4 articles.

First article

In the first article, rangatira declare this land ‘he w[h]enua rangatira’ — translated as ‘an independent state’.

Second article

In the second article, the rangatira say that they hold sovereignty in New Zealand and no foreigners can make laws here.

Third article

The third article says the rangatira will meet at Waitangi each autumn to pass laws and make decisions, and asks southern tribes to join them.

Fourth article

The fourth article declares that they will send a copy of He Whakaputanga to the British king, King William IV, asking him to be a protector of their independent state.

Question: Why were they asking the British king for protection? Because the French wanted to set up a colony in the Hokianga.

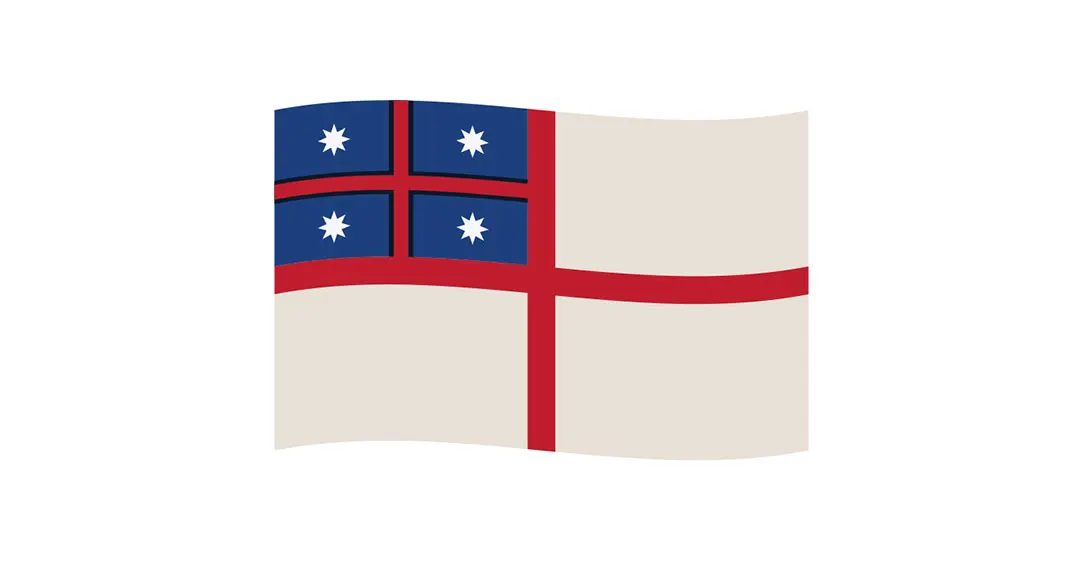

This is the flag that Māori rangatira chose in 1834 as the symbol of the United Tribes of New Zealand. It's also called Te Kara or ‘the colours’.

Nā wai i haina? | Who signed it?

Signing began on 28 October 1835 at Waitangi, and eventually, 52 rangatira signed.

The rangatira were all from Te Ika-a-Māui (the North Island). Most were from Te Tai Tokerau (Northland), but Te Hāpuku of Hawke’s Bay and Te Wherowhero of Waikato, 2 very influential rangatira, also signed.

He aha tōna tapu? | Why is it important?

He Whakaputanga is New Zealand’s first constitutional document — a document that defines Aotearoa as a nation, setting out who is in charge, and how it will be run. The word ‘whakaputanga’ is usually translated as ‘declaration’, but it also has the meaning of ‘emergence’ — it’s the beginning of a new country.

Test your knowledge of He Whakaputanga

Use the following words to fill the gaps (ellipses) in the text below:

independence

rangatira

king

missionary

quill

protection

colony.

He Whakaputanga — The Declaration of Independence 1835

In 1835, the Declaration of … was signed by 52 Māori …

Fifty of the chiefs came from the North, but Te Hāpuku of Hawke’s Bay and Te Wherowhero of the Waikato also signed. Te Wherowhero later became the first Māori …

The Declaration was drafted by the British Resident, James Busby. It was then translated into Māori by the … Henry Williams.

A young Māori boy, Eruera Pare Hongi, wrote the Māori text in his handwriting with a feather …

In part, the Declaration of Independence was a response to Frenchman Charles de Thierry wanting to set up a French … in the Hokianga.

He Whakaputanga has 4 parts.

In the first, rangatira declare this land ‘he w[h]enua rangatira’ — translated as ‘an independent state’.

In the second, the rangatira say that they hold sovereignty in New Zealand and no foreigners can make laws here.

The third part says the rangatira will meet at Waitangi each autumn to pass laws and make decisions, and asks southern tribes to join them.

The fourth declares that they will send a copy of He Whakaputanga to the British king, asking for his … of their independent state.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi — The Treaty of Waitangi

He aha te Tiriti? | What is the Treaty?

In the late 1830s, growing numbers of British settlers were arriving and the New Zealand Company had plans for extensive settlements. The Crown (British Government) decided a treaty was needed to control the unruly behaviour of British migrants, enforce British law, and stop land transactions between Māori and settlers.

A treaty is an agreement between independent nations. Te Tiriti o Waitangi was an agreement between Britain, represented by William Hobson, and New Zealand, represented by many rangatira. It was first signed at Waitangi on 6 February 1840. There are 9 sheets of Te Tiriti o Waitangi — 2 on parchment (stretched animal skin), and 7 on paper.

8 of these sheets are in te reo Māori, and one is in English. The sheets were taken around the country, sometimes by land but more often by sea, to be signed by as many rangatira as possible. In the end 542 rangatira signed, but also a few refused to sign. Some rangatira were not given a choice as the treaty was not taken to their part of the country.

He aha tōna tapu? | Why is it important?

Te Tiriti o Waitangi is the foundation on which our nation is built. It confirms Māori as tangata whenua, the first people of this country. It recognises that they have tino rangatiratanga (absolute authority or sovereignty) over their lands, resources and taonga (treasured possessions).

Te Tiriti o Waitangi has often been hotly debated. At times it has been ignored or the promises were broken, but for many New Zealanders it remains a source of hope and optimism for the future of our country.

From left to right: Hōne Heke and William Hobson.

Treaty articles

The Treaty of Waitangi is in 2 languages: te reo Māori and English.

First article

In the Māori text, Māori leaders gave the queen of England ‘te kawanatanga katoa’ or the complete governance or government over their land. So, in the Māori version, the British are not taking away Māori sovereignty but only overseeing Aotearoa New Zealand.

But the English text is quite different. The English version says that Māori ceded sovereignty — that means gave away their power to self-govern.

Question: Is the English and Māori text in this article the same or different?

Second article

In the second article, the Māori text says that the queen confirms or supports Māori tino rangatiratanga (chiefly authority) over all their lands, homes and taonga (treasured possessions). So here again, the Māori version says that Māori keep their power.

In the English text, Māori have ‘full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates, Forests, Fisheries and other properties’. The words ‘tino rangatiratanga’ or ‘chiefly authority’ are not used.

Question: Is the English and Māori text in this article the same or different?

Third article

The third article is the same in both versions. In it, the queen promises all the benefits of royal protection and equal rights as citizens. Māori and British will have equal rights.

Question: Is the English and Māori text in this article the same or different?

Fourth article

An unofficial ‘fourth article’ was agreed to verbally. It said that all people in New Zealand would be free to practice whichever religion they chose, including traditional Māori beliefs.

I mōhio rānei koe? | Did you know?

5 years earlier, Māori rangatira declared their sovereignty when they signed He Whakaputanga. They weren’t giving this up by signing Te Tiriti o Waitangi. There are different ideas about why the 2 versions are not the same. Perhaps you can discuss this with others? How could this have caused confusion?

Did you know that Queen Victoria was on the throne when the Treaty was signed?

He aha i kūraruraru ai Te Tiriti o Waitangi? | What happened after the Treaty was signed?

The Treaty of Waitangi was first drafted in English by William Hobson, and then translated into te reo Māori in one night by the missionary Henry Williams and his son.

Now, this is where it gets a bit tricky — the 2 versions say different things. Māori who signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi were agreeing to the Māori version and also the kōrero around it. It was natural to assume that the English version was the same. For rangatira, it was the Māori version that mattered. They also had a very different concept of government and land ownership.

Māori did not believe they ceded sovereignty. Remember the term sovereignty, meaning that you are the boss in your own country? The word kāwanatanga is also about power. It means ‘governorship’, where you have some control but not all. A helpful way to think about this is that you have kāwanatanga in your bedroom. You can rearrange furniture or decide who can enter. But your parents have sovereignty (supreme power) — you’d need to ask their permission if you wanted to paint the walls, for example.

Conflict and broken promises

Land sales

In the decades after 1840, the government’s appetite for land grew as more and more European settlers arrived. Some sales were fair and legal. Others were forced on Māori. Often, important conditions of sale, such as the creation of reserves for Māori, were never met. Different versions of the Treaty contributed to misunderstandings.

European-style land sales were not part of Māori culture. Early on, Māori considered land transactions as the starting point for mutually beneficial relationships with Pākehā and did not accept that selling meant losing overall authority over the land. It soon became clear that Europeans saw things differently.

Wars

Between 1845 and the 1880s there were several wars between the government and some iwi over land and sovereignty. Māori resisted invasion in Taranaki, Waikato and elsewhere. In response, the government confiscated huge areas of the most fertile land — some of it even from Māori who had fought on their side. The promises of Te Tiriti o Waitangi were broken.

How did Māori respond?

Maōri actively protested against the taking of their land and sovereignty, and the erosion of Māori rights that Te Tiriti o Waitangi promised. Māori strategies for getting their voices heard included passive resistance, land occupation, marches, court cases, and as a last resort — in the mid-1800s — armed resistance.

Image credit: H M S North Star destroying Pomare’s pā, Otiuhu, Bay of Islands, 1845 by John Williams. Ref: A-079-032 Alexander Turnbull Library.

Ka whaimana tonu te Tiriti a ngā tau kei te heke mai? | What does Te Tiriti o Waitangi mean for our future?

Te Tiriti o Waitangi is still relevant today.

For a long time, the English version of the Treaty was the one that was emphasised. But now, there is a better understanding of the differences between the 2 versions. As a country, we are still working out how to fulfil the promises of the version written in te reo Māori.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi affirmed and still affirms the rights of Māori to live as Māori, making decisions that support the wellbeing and aspirations of Māori communities based on Māori understandings, values, practices and knowledge.

Since 1975, the Waitangi Tribunal has been addressing grievances and breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi by the Crown. Many iwi have settled with the Crown, which means that they have received and accepted an apology for what has happened and are working together for a better future through the Treaty settlement process. It’s important to acknowledge that the redress provided can never fully make up for what Māori have lost; the sums paid are very small compared to what has been taken by the Crown. There is also a government department, called Te Arawhiti (meaning ‘the bridge’), that is dedicated to improving Māori-Crown relationships and is in charge of carrying out Treaty settlements.

In 1840, Te Tiriti o Waitangi made space for tauiwi settlers and introduced British law. Nearly 2 centuries later it is a guideline for sharing our country and power — so that we can all call these islands home.

I mōhio rānei koe? | Did you know?

Tauiwi is what non-Māori or people from afar are called in te reo Māori.

I ahatia rā i tō rohe? | What happened in your rohe (area)?

Below are some pātai (questions) to get you thinking about what happened in your own rohe.

Before you begin, watch the map table story The Voyages of Te Tiriti in He Tohu or on YouTube (YouTube video, 3:20).

Pick at least one Treaty sheet and draw its journey around the country on the map. You can colour-in the map with landmarks (lakes, rivers, mountains etc.) of your choice!

Prompts and questions

Did any of your tūpuna sign He Whakaputanga or Te Tiriti o Waitangi? Do you know the names of rangatira who signed from your iwi?

Mark a cross on the area you come from. Was Te Tiriti o Waitangi signed in your location?

Who are tangata whenua of the rohe (area)? What stories do you know about them?

After watching the video Voyages of Te Tiriti, write down or colour-in areas on the map where the Treaty did not go. How would you feel if you were one of the rangatira who didn’t have the option to sign Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840?

Find out more

Look on the interactives in He Tohu or the NZ History website.

Here are some helpful links to find out more:

Te Tiriti o Waitangi — The Treaty of Waitangi

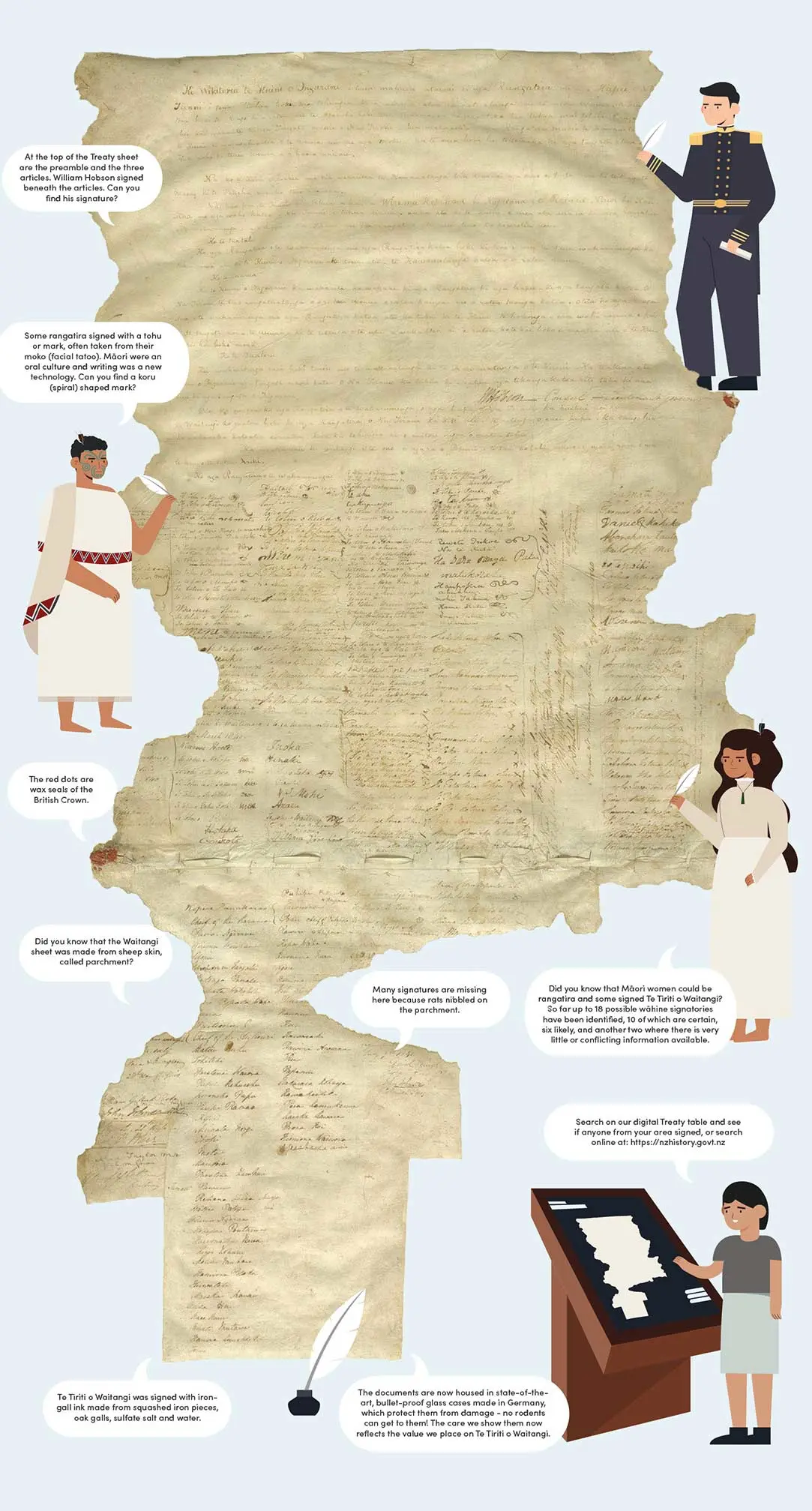

Long description — information in Te Tiriti sheet image

At the top of each of the Treaty sheets is the preamble and the 3 articles. William Hobson signed beneath the articles. Can you find his signature?

Some rangatira signed with a tohu or mark, often taken from their moko (facial tattoo). Māori were an oral culture and writing was a new technology. Can you find a koru (spiral) shaped mark?

The red dots are wax seals of the British Crown.

Did you know that the Waitangi sheet was made from sheep skin, called parchment?

Many signatures are missing here because rats nibbled on the parchment.

Did you know that Māori women could be rangatira and some signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi? So far up to 18 possible wāhine signatories have been identified, 10 of which are certain, 6 likely, and another 2 where there is very little or conflicting information available.

Search on our digital Treaty table and see if anyone from your area signed, or search online at NZHistory.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed with iron-gall ink made from squashed iron pieces, oak galls, sulfate salt and water.

The documents are now housed in state-of-the-art, bullet-proof glass cases made in Germany, which protect them from damage — no rodents can get to them! The care we show them now reflects the value we place on Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Preserving the documents — inside the document room

The document room houses the originals of the 3 documents which shaped Aotearoa New Zealand. It’s all about preserving them for future generations. Te Tiriti o Waitangi in particular hasn’t always been looked after. Between 1877 and 1908 the Treaty sheets were kept in the basement of the Government Buildings in Wellington and neglected; rats and mice nibbled on the Treaty sheets!

Today we take good care of the documents with special glass cases, low light levels, and temperature control to preserve them.

Questions

What do you think of the way Te Tiriti o Waitangi was treated in the past?

Were the Treaty sheets shown respect and care?

If you visited the document room, how did it make you feel to be in the presence of the original documents?

I mōhio rānei koe? | Did you know?

For Māori, the document room is a tapu or sacred space, because the spirits of the ancestors who signed may still linger. That’s why there is a waiwhakanoa bowl, a water bowl, at the exit so people can cleanse themselves before they return to the noa or normal realm.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi at He Tohu. Photo by Mark Beatty, National Library of New Zealand.

Te Petihana Whakamana Pōti Wahine, 1893 — The Women’s Suffrage Petition

What was life like in the 1800s for wāhine in Aotearoa?

In pre-European times, some Māori women were powerful leaders in their own hapū (sub-tribes) and iwi (tribes). They fought in battles, owned property, and retained it after marriage. They were political decision-makers. The introduction of British laws and ideas about the ‘proper place’ of women conflicted with their values and reduced their rights and recognition. In the late 19th century (1800s), Māori women faced many pressing issues that affected Māori society generally.

Many tauiwi women worked in their homes, on their families’ farms, or as domestic servants for other people. They played very limited roles in public life. Many women wanted more opportunities in education and paid employment. Few girls went to secondary school, and women were excluded from many jobs.

Here are some helpful definitions:

Suffrage: The right to vote in political elections.

Suffragist: A person supporting suffrage, especially for women.

Petition: A request to Parliament for change.

Meri Te Tai Mangakāhia

A ‘monster’ petition

Until 1893, women were not able to vote in elections for Parliament, but their petitions had to be received.

The Women’s Suffrage Petition called for women to have the same voting rights as men.

1893 was an election year and the 1893 petition was, in the words of prominent suffragist Kate Sheppard, ‘a monster’. Combined with a number of smaller petitions, it had 31,872 signatures representing almost a quarter of all adult women in the country.

In Kate Sheppard’s dining room, volunteers, including members of the Christchurch branch of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, glued all 546 pages together and wound them around a broom handle into one big roll. The finished petition is 274 metres long. Unrolled, it would reach from the National Library in Wellington, across the road, and up the steps of Parliament. That’s a long way!

1893 was a monumental year for Māori women as well. Meri Te Tai Mangakāhia became the first woman to speak in any Parliament in Aotearoa New Zealand. She brought a motion to Te Kotahitanga (the Māori Parliament) for women to have the right to vote and stand. This led to wāhine Māori gaining the right to vote and the formation of Ngā Kōmiti Wāhine (tribally based Māori women’s committees).

Did you know that you had to be 21 years or older to sign the petition? But some women were as young as 17 years! They couldn’t wait to vote!

Nā wai tēnei mea Te Petihana Whakamana Pōti Wahine i anga whakamua? | Who was behind the Women’s Suffrage Petition?

Fighting for the right to vote was a huge team effort. There were a number of groups who supported the suffrage movement, but it was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union who were the key organisers of the petitions in 1891, 1892 and 1893. Other groups included the Women’s Franchise League and the Dunedin Tailoresses’ Union. Hundreds of volunteers around the country worked tirelessly for several months, knocking on doors to collect signatures one by one.

Māori women were also involved in the suffrage campaign, many signing the Women’s Suffrage Petition or campaigning to have a greater voice in Māori forums.

Nā wai i haina. I hainatia i hea? | Who signed the petition, and where?

To sign the Petition, you needed to be 21 years and older, but some younger women signed and about 30 men also signed. Aotearoa New Zealand was a largely rural nation in the late 19th century — there are signatures from as far away as Ahipara in the far north and Bluff in the south.

Women from all walks of life signed the Petition — they were teachers, students, nurses, business owners, domestic servants and more. Their backgrounds range in wealth, education and social status.

Did any of your ancestors sign the Women’s Suffrage Petition? Perhaps women from your town signed — you can find this out on the interactives in He Tohu or at NZHistory — Women and the vote.

I te mutunga iho | Parliament listens

In July 1893, Sir John Hall delivered the Petition to Parliament in a ‘wheelbarrow’.

He had the document unrolled down the middle of the debating chamber, until it hit the end wall with a thud.

Note and question: The story of the wheelbarrow is a myth. It is not backed up by historical evidence and may be a detail that was added later. Fact or fiction? What do you think?

In 1893, Aotearoa New Zealand became the first self-governing country in the world in which all women citizens gained the right to vote in general elections. This was a landmark achievement in the struggle for gender equality and something we can still be proud of. It is a great example of women and men working together to create change.

For New Zealanders, that victory is a proud moment in a struggle for equality that is still continuing.

Petitions today

Aotearoa New Zealand has a rich tradition of petitions to government. For example, in 2015 Ōtorohanga College students Waimarama Anderson and Leah Bell delivered a petition to Parliament demanding that the New Zealand Land Wars be remembered and taught in school. They were 14 and 16 years old at the time. Their petition was successful.

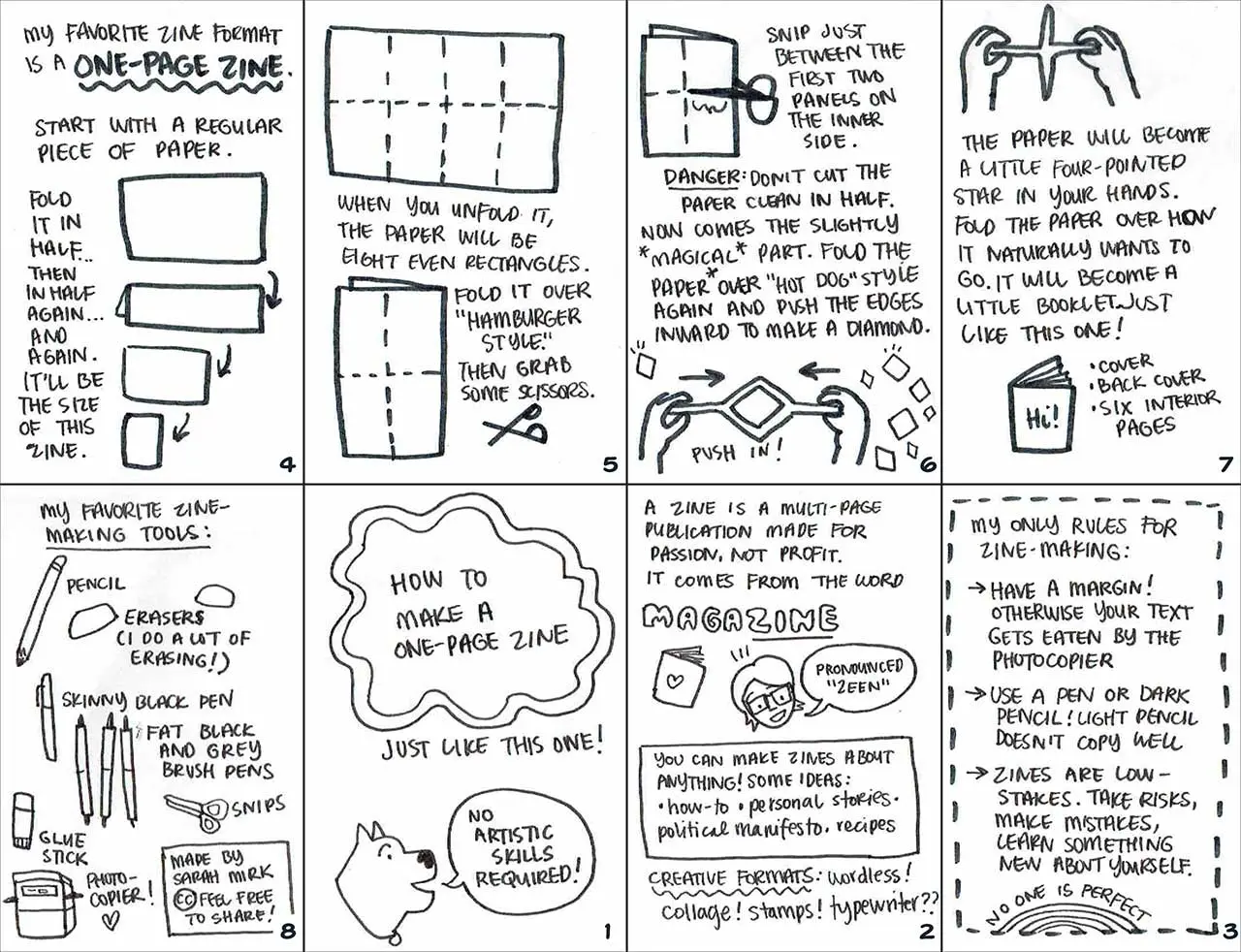

Make an upstanding zine

Draw a zine about one of the stories your whanaunga (relative) has shared with you.

Choose a family or community member who is much older than you and ask them about how things have changed in Aotearoa New Zealand in their lifetime.

Ask for specific examples and stories. Select one story from your interview that you can turn into a small zine. Here are some questions you could ask:

What was life like for women when you were growing up?

Were you supported in following your dreams?

Did you feel treated equally to men in the household, at school and at work?

Did you learn about the Treaty and the Declaration of Independence at school?

What did you do on Waitangi Day back in the day?

What could we do together for Waitangi Day next year?

Fold your zine first and then create your story!

Made by Sarah Mirk. Creative Commons. Feel free to share! Thanks also to Wellington Zinefest!

Long description — How to make a one-page zine

Instructions on how to make a one-page zine, presented as a zine. The content of each panel is as follows.

Panel 1

How to make a one-page zine

Just like this one!

No artistic skills required!

Panel 2

A zine is a multi-page publication made for passion, not profit. It comes from the word ‘magazine’ — pronounced ‘zeen’.

You can make zines about anything! Some ideas:

how-to

personal stories

political manifesto

recipes.

Creative formats:

wordless!

collage!

stamps!

typewriter??

Panel 3

My only rules for zine-making:

Have a margin! Otherwise your text gets eaten by the photocopier.

Use a pen or dark pencil! Light pencil doesn't copy well.

Zines are low-stakes. Take risks, make mistakes, learn something new about yourself.

No one is perfect.

Panel 4

My favourite zine format is a one-page zine.

Start with a regular piece of paper.

Fold it in half.

Then in half again.

And again.

It'll be the size of this zine.

Panel 5

When you unfold it, the paper will be 8 even rectangles.

Fold it over ‘hamburger style’ then grab some scissors.

Panel 6

Snip just between the first 2 panels on the inner side.

Danger: Don't cut the paper clean in half.

Now comes the slightly magical part. Fold the paper over ‘hot dog’ style again and push the edges inward to make a diamond. Push in!

Panel 7

The paper will become a little 4-pointed star in your hands.

Fold the paper over how it naturally wants to go. It will become a little booklet just like this one!

Cover

Backcover

6 interior pages.

Panel 8

My favourite zine-making tools:

pencil

erasers (I do a lot of erasing!)

skinny black pen

fat black and grey brush pens

snips

glue stick

photocopier.

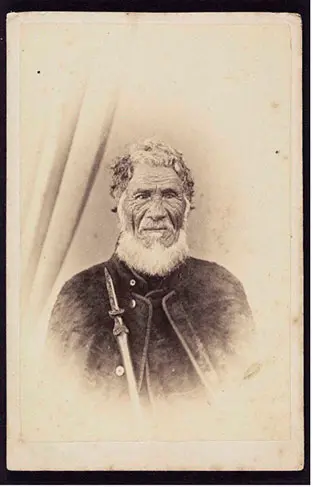

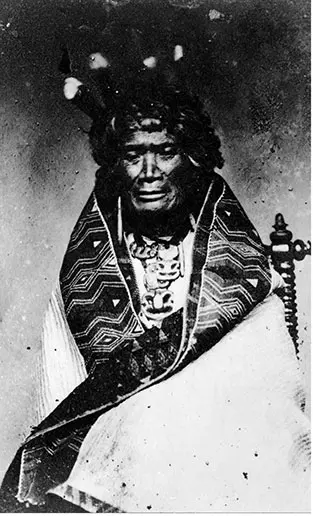

Who’s who?

Now let’s look at some key people who signed the documents.

Below are images of 5 of the many people who signed the documents in He Tohu:

Eruera Maihi Patuone

Hōne Heke

Te Rangi Topeora

Kate Wilson Sheppard

Ada Wells.

Do some research and write a short biography of at least one of these.

Questions

Which document did they sign?

What was the most interesting thing you learnt about them in your research?

Have a look here to help you research: NZHistory

Eruera Maihi Patuone

Image credit: Portrait of Eruera Maihi Patuone, ca 1870. Photographer unknown. Ref: PA2-2736 Alexander Turnbull Library.

Hōne Heke

Hōne Heke (centre). Image credit: The warrior chieftains of New Zealand, 1846 by Joseph Jenner Merrett. Ref: C-012-019 Alexander Turnbull Library.

Te Rangi Topeora

Image credit: Portrait of Te Rangi Topeora, ca 1840. Photographer unknown. Ref: 1/2-058452-F Alexander Turnbull Library.

Kate Wilson Sheppard

Image credit: Kate Wilson Sheppard, 1905 by W Sidney Smith. Ref: 1/2-C-09028-F Alexander Turnbull Library.

Ada Wells

Image credit: Photograph of Ada Wells from Woman Today magazine, ca 1910. Photographer unknown. Ref: 1/2-C-016534-F Alexander Turnbull Library.

Make a fact-finding fortune teller

Photocopy, or cut out the fortune teller around the outside of the template, and fold.

Start with the reverse side facing you.

Fold it over into a triangle.

Unfold it.

Fold it the other way.

Unfold it. Your paper should have a crease in the shape of an ‘x’.

Take each of the 4 corners of the paper and fold them into the centre. Your paper should form 4 triangles.

Flip your paper over.

Fold all 4 corners into the centre again.

Flip your paper over.

Fold it sideways, ensuring the creases are strong.

Unfold it.

Fold it down.

Unfold and flip it.

Put your fingers into the 4 flaps of colour.

Fortune teller questions

Here are the questions in the fortune teller. The words in bold for each question is the correct answer.

Tahi

What day was Te Tiriti o Waitangi signed at Waitangi?

A: 25th April

B: 6th February

C: 3rd February

Rua

Did any men sign the Women’s Suffrage Petition?

A: No, it was for women only

B: Yes, about 30 men signed

Toru

How many women signed the Women’s Suffrage Petition?

A: over 13,000

B: over 31,000

C: over 300,000

Whā

What did the rangatira declare in 1835?

A: Dependence

B: Independence

C: Colonisation

Rima

Could women sign the Treaty?

A: Yes, women could be rangatira and sign

B: No, only men singed

Ono

How many Europeans lived in New Zealand in 1840?

A: 200,000

B: 20,000

C: 2,000

Whitu

How many Māori lived in New Zealand in 1840?

A: 80,000

B: 8,000

C: 2,000

Waru

The Treaty is an agreement between which parties?

A: Māori and the British Crown

B: Māori and the French

C: Māori and the British settlers

The consequences of broken promises

After the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the promises it made were broken many times. Māori weren’t given the power of decision-making guaranteed by the Treaty. During the New Zealand Wars, land was taken and Māori were marginalised. Investigate a historic event of your choice and find out more about it. What happened? Who was involved? What was a consequence of the event?

Here are some events you could use for your research:

The invasion of Parihaka 1881

The 1975 Land March

First kohanga reo opens 1982

Māori becomes an official language 1987.

Headings for your research

Date

Event

What happened?

Who was involved?

What were the consequences?

Creating your own tohu (sign/mark)

Many rangatira signed He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi by replicating the image of their tā moko (facial tattoos). Some chose a symbol to represent their signature. The Women’s Suffrage signatories used different coloured ink.

Have a go at designing your own tohu (mark).

Questions

What symbol and colours would you choose?

Write why you designed it this way.

Reflections. Express yourself!

What have you learnt about the history of Aotearoa New Zealand?

How might you help shape Aotearoa New Zealand for the future?

Sometimes learning about these important cultural documents and their impact can have an effect on people. You can express your feelings here.

Write some prose or poetry, design your own flag, do a cut-and-paste collage, or illustrate your thoughts below.

If English is your second language, you could write in your mother tongue, or if you’re learning another language, you may want to use it here.

Tino pai rangatahi mā, you’ve completed the workbook!

Hopefully, you have a new perspective on this incredibly special country, and new ways to honour those who signed the documents, made sacrifices and were impacted, as well as those who forge ahead to be change-makers today and fight injustice.

Perhaps you will choose to join them and become a change-making super-citizen!

It doesn’t matter how small the gesture, it all counts; use te reo proudly, learn more about your own culture, and be an upstander to inequality.

You can be the change you want to see for a better Aotearoa!

Me he pito mata. Whāngaihia, kia whakatipu haemata!

Glossary

Crown: The royal governing power of a country that has a king or queen. Today it also refers to the government.

Declaration: An official announcement or statement of fact.

Election: A way of choosing who will be in Parliament by voting.

Kāwana: Governor; the representative of the Crown in a British colony.

Kāwanatanga: Governorship/Government. The role of a governor.

Missionary: A person who has been sent to a foreign country to teach their religion to the people who live there.

Petition: A formal written request, typically one signed by many people, appealing to authority in respect of a particular cause.

Rangatira: Chief or leader.

Rangatiratanga: Chieftainship; the right to exercise authority; ownership; leadership of a social group.

Sovereignty: The power or authority to rule; the power of a country to control its own government.

Tangata whenua: Māori, indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand who are connected to the land. Tangata means ‘people’. Whenua means ‘land’ and ‘placenta’.

Tauiwi: A non-Māori person, someone from afar.

Tohu: A sign, mark or signature.

Treaty: An international agreement between countries. A treaty is legally binding under international law.

Te Puna Foundation

A shoutout to the Te Puna Foundation. Perhaps you travelled to He Tohu with their help?

The Te Puna Foundation He Tohu Travel Fund works within the National Library to support schools from all over Aotearoa, enabling them to participate in one of our He Tohu learning programmes.

Tau kē Te Puna Foundation!

About the He Tohu exhibition

The He Tohu Exhibition is presented by Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga and the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, which are part of the Department of Internal Affairs Te Tari Taiwhenua.

For more information about He Tohu or to book a school visit He Tohu.

Formally opened on 19 May 2017, He Tohu was developed in partnership between the Crown and Māori, with significant input from women’s groups nationwide. Māori were represented by iwi leaders from throughout the country, particularly Te Ātiawa, Taranaki whānui and Ngāti Toa Rangatira.

In developing the exhibition, the Department of Internal Affairs He Tohu development team were also guided by two advisory groups, made up of leading Māori experts in areas including history, design and language.

He Tohu at the National Library replaced the previous display of these documents in the Constitution Room at Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, however, the documents remain under the statutory care of the Chief Archivist. The Chief Archivist and the conservators at Archives New Zealand are responsible for their care and preservation.

In 2019, He Tohu Tāmaki opened at the National Library in Auckland. It includes a virtual reality exploration of the Wellington He Tohu Exhibition document room, and learning programmes for school groups.

Related content

Women’s Suffrage Petition | Te Petihana Whakamana Pōti Wahine

Use our workbook and explore its activities to learn about the Women’s Suffrage Petition | Te Petihana Whakamana Pōti Wahine. Download and print the workbook or read the online version.

Women’s Suffrage Petition | Te Petihana Whakamana Pōti Wahine — workbook teacher support

Teachers — find out how our Women’s Suffrage Petition workbook aligns with the Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories curriculum. Our teacher workbook also has tips to plan your lessons and answers to the workbook activities.

Precious workbook — Ages 7 to 11

Use our fun workbook to discover why some things are precious and uncover the things that are precious to you. Either grab a piece of paper and work through the activities from the webpage or print the booklet. Suitable for ages 7 to 11.

Precious workbook — Ages 11 and up

This book will guide you through the role of libraries, museums and galleries in caring for the precious objects of Aotearoa New Zealand. You will learn about finding, caring for, and exhibiting your own precious object. Suitable for ages 11 and up.