The bee takes flight again

Clare Butler, Digitisation Advisor Māori, shares the joys of te reo Māori, bees and books.

You can also read this blog in te reo Māori — Ka rere anō te pī

Celebrating te reo Māori and bees

This month we celebrate the 50th anniversary for the Te Reo Māori Language Petition, it’s Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori and, its also Bee Aware month!

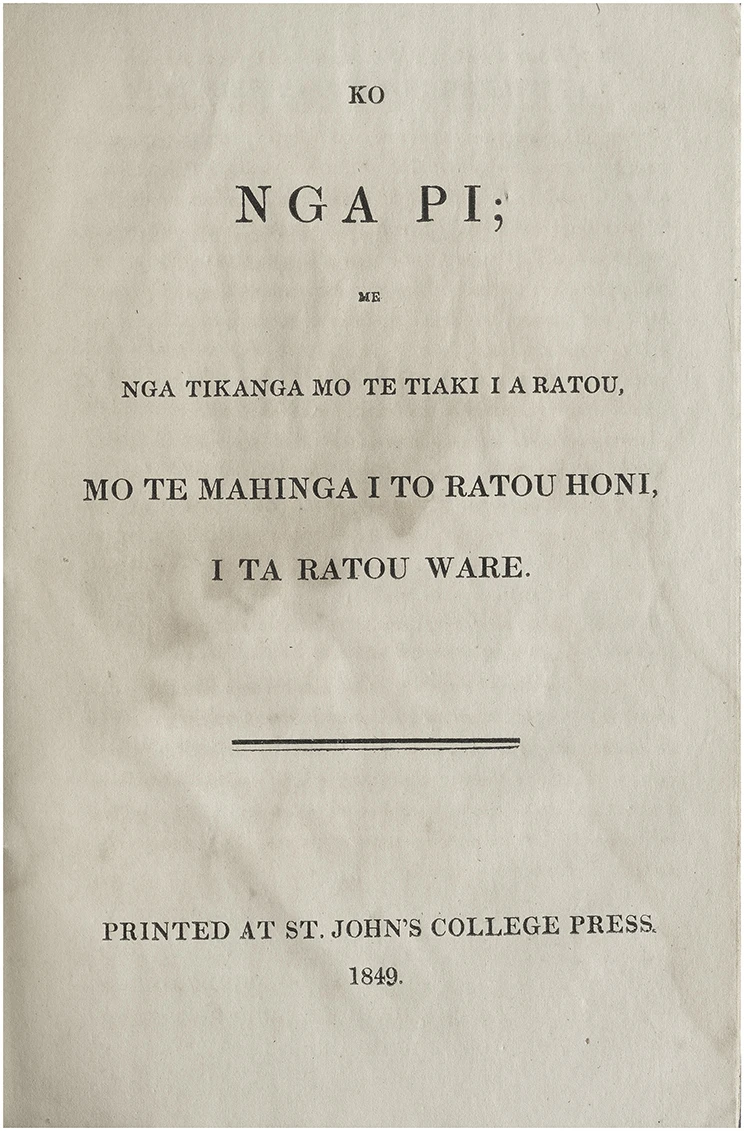

All of which means it’s a perfect opportunity to highlight Ko Ngā Pī by William Cotton. Ko Ngā Pī is the first book to be published in te reo Māori about bees and beekeeping in New Zealand.

Bees in Aotearoa

There are twenty-eight species of ngaro huruhuru | native bees in New Zealand. Ngaro huruhuru pollinate plants and collect nectar but they don’t create honey in large quantities, and they live in family nests in the ground, rather than hives. Elsdon Best reported that although ngaro huruhuru didn’t produce honey, Māori collected nectar directly from the flowers of the kōrari, rātā, pōhutukawa and rewarewa by plucking the flowers and tapping them into small gourds. He noted that it was a tedious task, often performed by young folk and that the amount of nectar collected was hard to know. 1

Honeybees were first brought to Aotearoa in 1839. Mary Bumby, a sister of the Methodist missionary Reverend John Hewgill Bumby, brought two hives with her from England. The Bumbys settled at Māngungu Mission Station in the Hokianga, and although John drowned the following year, Mary and the bees remained. Her hives were followed by others, including three brought over from Sydney by James Busby in 1843.

The New Zealand bush environment suited the honeybees and they produced honey with unique New Zealand flavours such as mānuka, pōhutukawa, rewarewa and rātā.

William Charles Cotton — The Grand Bee Master

Reverend William Charles Cotton (1813-1879), the chaplain to Bishop Selwyn at St John’s College, was an enthusiastic beekeeper and is largely credited with introducing the skills of beekeeping to Aotearoa.

While in England he had written My Bee Book (1842), the last chapter of which outlined his plans for transferring honeybees to New Zealand. Even before getting to New Zealand he was already planning to train Māori in bee-keeping, saying ‘I hope a Bee will never be killed in New Zealand, for I shall start the native Bee keeper on the no killing way ...’ 2 At the time it was normal to kill all the bees to be able to collect the honey from the hive; Cotton was one of the early advocates of using smoke to sedate the bees, rather than killing them.

Unfortunately, his hives did not survive the trip out, but in March 1844 he was given two swarms from Busby’s hive at Waitangi, the second of which survived. He used his hives to educate colonists and Māori about honeybees and beekeeping.

Māori interest in honeybees and honey

There was a clear interest from Māori in learning more about these new insects and their honey. An entry from Cotton’s 1844 journal describes showing Renata, William King and other Māori his bees and giving them some honey to taste. They exclaimed ‘He mea reka wakakarakara’, which Cotton translated as ‘a very exceeding sweet taste’. 3

Sketch of two young Māori men, Kerenana and Reihana sitting next to Cotton’s bees (January 1845). Ref: E-111-1-053. Alexander Turnbull Library.

As part of sharing his beekeeping knowledge, Cotton wrote a series of articles called Hints of the management of bees that were published in the New Zealander between March 1847 and February 1848. In the introduction to these articles, the paper mentioned that Māori at Otaki had taken swarms from Cotton’s hives and now had several hives themselves.4 Cotton commented on the speed in which Māori at Otaki learnt to create straw hives, due, he thought, to their knowledge and experience of weaving and kete making. 5

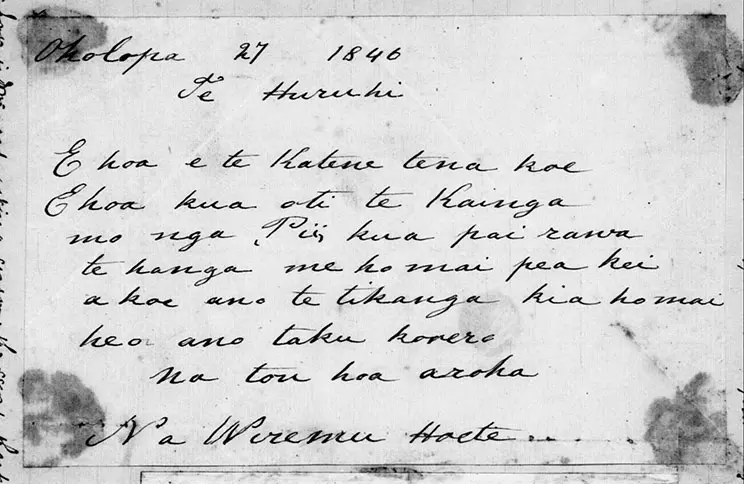

The letter pictured below, is preserved in one of Cotton’s journals and is one of two letters from Wiremu Hoete (Ngāti Pāoa). Hoete lived at Te Huruhi, on Waiheke Island. He was a rangitira, a scholar and one of the signatories to Te Tiriti o Waitangi at Karaka Bay in March 1840.

In this letter Hoete wrote “E hoa kua oti te Kainga mo nga Pii, kua pai rawa te hanga me homai pea kei a koe ano te tikanga kia homai | My friend the beehives are finished. They are well made. Perhaps I could have them, but that decision is up to you."

Volume 11: William Charles Cotton : Journal of a Residence at St John’s College, 6 June-20 November 1846; A Voyage to Wellington; A Residence in the Otaki District; and A Journey to Auckland, via Whanganui and Taranaki, ending 23 March 1847. Ref: 997473. Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, SAFE/DLMS 43.

Ko Ngā Pī

As a result of Māori interest in honeybees and honey, William Cotton wrote Ko Ngā Pī. Published in 1849, the 21-page book explores how to look after bees. It also describes how to process honey and beewax and was written in te reo Māori. In the book, Cotton reflects on the nature of bees writing:

“He iwi mahio te pi, he iwi kaha ki te mahi. No roto i nga puawai o nga rakau, o nga otaota, ta ratou honi. Ko ta ratou e tino pai ai ko te hanga honi. E kore ratou e pai ki te tikanga a etahi tangata, ki te oho mangere i te awatea. Na te Atua i homai te ngakau mohio, te ngakau mahi ki a ratou.”

“Bees are a knowing species, that are very industrious. Their honey comes from the blossoms of the trees and other vegetation. They are very efficient at making honey. They are not likened to some people, who are idle in the day. It was the Lord who gave them the understanding and the work ethic."

Cover of Ko nga pi : me nga tikanga mo te tiaki i a ratou, mo te mahinga i to ratou honi, i ta ratou ware.

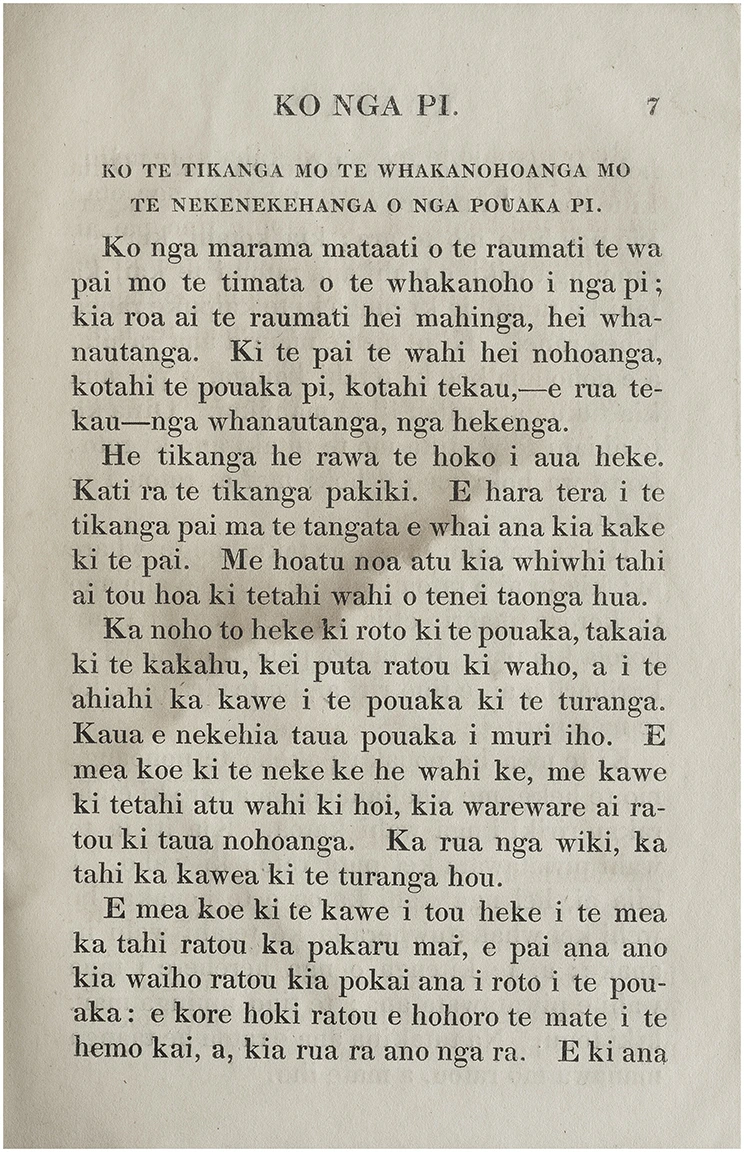

Cotton includes practical advice, for example, in chapter 2 he provides information about moving bees and says ‘Ko nga marama mataati o te raumati te wa pai mo te timata o te whakanoho i nga pi | The best time to start to resettle bees is in the hottest months of summer’. (p.7) The chapter then goes on to give more detailed instructions on how to do this.

Cotton also shares advice about the placement of beehives ‘Kia aro nui ki te ra, kia mahana ai i te ata: otiia me uhi, kei ngaua kinotia e te ra, kei kino i te ua. | Turn to the sun, to be warm in the morning: However cover, in case of sunburn or will be spoilt by the rain’. (p.6)

Ko nga pi : me nga tikanga mo te tiaki i a ratou, mo te mahinga i to ratou honi, i ta ratou ware. (P.7)

Translating Ko Ngā Pī

Te reo Māori translator Joy Ngaropo-Hau, was recently commissioned by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga to undertake a translation of Ko Ngā Pī. In an article about this translation work , Joy says “It was the biggest challenge I’d ever faced in my translation work, and my biggest learning curve,”. The subject matter added a layer of complexity to the text as did William Cotton's te reo Māori.

Joy understands Cotton began learning te reo Māori on his voyage to New Zealand, taught by a Māori deckhand. However, after undertaking the translation of Ko Nga Pī, she considers his education in te reo Māori was incomplete and says ‘There were wrong words used; there were words that didn’t make sense, so I got a bit hōhā with it, but when things get tough, I'm not one to give up.’ 6

Honi or mīere?

In the book Cotton uses honi as a loan word for honey, today people could also use mīere. Mīere first appears in William Williams’ A dictionary of the New Zealand language in the 3rd edition (1871), as a word for honey as well as other sweet things.

Missionary and printer William Colenso said in an 1892 letter that mīere was the word for honey used by local Māori around Dannevirke, but that it wasn’t one he’d heard elsewhere. His correspondent, W. F. (William Francis) Gordon wrote on the bottom of the letter that some people thought mīere came from early French missionaries and was derived from the French miel. 7

Interestingly, Edward Treagar, in his Maori-Polynesian Comparative Dictionary of 1891, questions this, suggesting that the various Polynesian words for honey (meli, mele, melie, hone, huamelie, mere) were similar, even from places without a French presence. 8

Both honi and mīere are noted in later editions of Williams’ dictionary, as loan words for honey. 9

Māori and modern day beekeeping

New Zealand has developed a worldwide reputation for its mānuka honey with its antibacterial properties. Māori had always known about the health benefits of mānuka, using it in different forms to treat skin conditions, burns, fevers and colds and as a sedative. 10

Today, some young Māori, such as Mere Vaka, seen here on Country Calendar in 2019, are going back to whānau land and establishing beekeeping businesses. Iwi such as Ngāti Kuia or Te Rarawa are partnering with training organisations to provide courses in beekeeping for rangitahi, investing in honey companies as Ngāi Tahu has, or establishing co-operatives such as the Ngāti Porou Tairāwhiti Mīere Collective to bring the benefits of beekeeping back to the local people.

Digitisation of Ko Ngā Pī

Ko Ngā Pī is part of the National Library’s digitisation project Ngā Tānga Reo Māori, which aims to provide greater access to Māori language content and Mātauranga Māori. Digitised texts will be, with consent, placed on the Papers Past website under the Books section. Ko Ngā Pī should be available online in the second half of 2023.

Interested to read more on bees?

The Alexander Turnbull Library holds around 400 books on bees and beekeeping in the Earp Collection. Edgar Allan Earp (1874–1963) was a senior governmental apiary instructor and donated this collection to the Library in memory of his wife.

You can also find many articles Earp wrote himself in the New Zealand Journal of Agriculture, available on Papers Past.

Thank you

This was a collaboration piece from members of the team working on the Ngā Tānga Reo Māori Digitisation project. Many thanks to Melanie Lovell-Smith for her research expertise and editing skills.

Footnotes

Elsdon Best, Forest Lore of the Māori. Wellington: E. C. Keating, 1977, p.100.

William Cotton, My Bee Book. London: J. G. F. & J. Rivington, 1842, p.356.

Entry for Saturday 16 March 1844, Volume 7: William Charles Cotton: Journal of a Residence at St. John’s College, The Waimate, 2 March 1844-25 August 1844. Ref 997468. State Library New South Wales.

New Zealander: 13 March 1847, p. 3

Peter Barrett, William Charles Cotton: Grand Bee Master of New Zealand, 1842 to 1847. Springwood, N.S.W: Peter Barrett, 1997, pp100-101;104.

Caitlin Sykes, “Joy of Bees”, in Heritage New Zealand Kōanga Spring 2022, pp.12-14.

Letter to W.F. Gordon re Maori word for honey (CA000162/001/0008/0002)

Herbert W. Williams, A Dictionary of the Māori Language, 6th ed. Wellington: Government Printer, 1957, Appendix.

Edward Tregear, Maori-Polynesian Comparative Dictionary. Wellington, Lyon and Blair, 1891, p.241.

Māori medicine | Rongoā Māori — Te Papa Tongarewa.