Seeing Red

This talk was delivered at the National Library of New Zealand on Tuesday 28 July, 2015. It is part of a series of lunchtime talks supporting the library's Contemporary Conversation exhibition.

Jared Davidson is Archivist at Archives New Zealand, but views are his own.

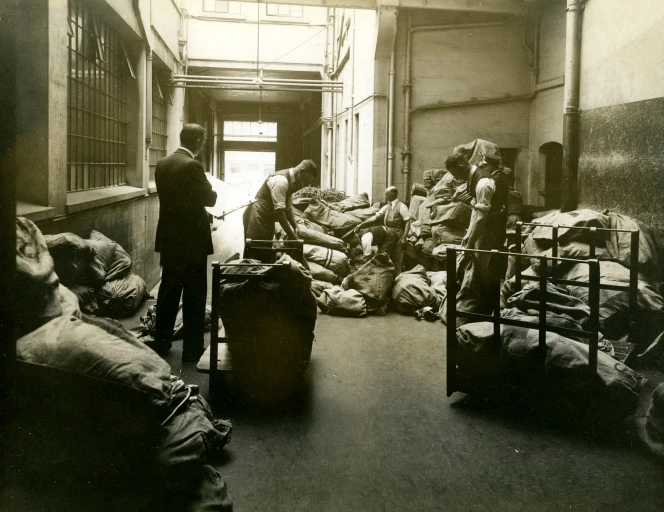

Chief Post Office Mailroom, Wellington 1920. AAME 8106 W5603 Box 126, Archives New Zealand

When Defence Minister James Allen learned of his son’s death on a remote Dardanelles beach, he penned a remarkable letter to his colleague commanding the New Zealand forces there, General Alexander Godley:

Only yesterday I received the sad news of my son being killed in action, and am very grateful to you and the expeditionary force for the kind telegram you sent me… your losses will be heavy and there are many sad hearts in New Zealand today. At the same time let me give you this positive assurance that sad though we may be, we are proud to know that our sons have done their duty… those of them who are gone have died the best of deaths, and those who return will come back justified with the deeds they have done.

Privately, Allen thought otherwise. The costly Gallipoli campaign was ‘ill-conceived and mad.’ His letter to the man he thought should never have been in charge was a stoic act of self-censorship—a way to cope with grief of losing his soldier son to war. In the colloquialism of the day, Allen played the game.

Yet as New Zealand’s prime minister in the absence of William Massey and Joseph Ward, Allen had no need to self-censor his correspondence. He was one of the few in New Zealand whose mail was not liable to be opened by censors.

The majority of the general public had no such luxury. From the outbreak of the First World War until November 1920, the private letters of mothers, lovers, internees and workmates were subject to a strict censorship. A team of diligent readers in post offices around the country poured over pounds and pounds of mail. Some were stamped and sent on. Others made their way into the hands of police commissioners. In an era when post was paramount, the wartime censorship of correspondence heralded the largest state invasion of Pakeha private life in New Zealand’s history.

For some this was entirely justified. Sons and daughters of the empire were fighting the bloodiest and most industrialised conflict the world had ever seen. New Zealand soldiers were killed or maimed in higher numbers than ever before; loose pens giving away military intelligence was as good as stabbing them in the back.

Yet home front censorship quickly departed from purely military information, and increased in both severity and political significance during the war. By 1920, writers critical of the National Coalition government and its wartime policies were under surveillance, had their mail detained, and homes or offices raided. Some were jailed, or in the case of labourer Henry Murphy, deported from the country.

My research has found that close to 1.2 million letters, postcards, and packages were opened and examined by the New Zealand military during the First World War. I don’t know the exact number that were withheld or destroyed. But some of the most subversive ended up in the Army Department’s ‘Secret Registry: Confidential Series’ now held at Archives New Zealand. Amongst the series are fifty-seven letters, as well as extracts from seventeen others. These seventy-four examples give a fascinating insight into postal censorship, state attitudes towards dissent, and the New Zealand home front during the First World War.

I want to share a few of these letters with you today. But first I’ll give an overview of how postal censorship worked. And although I’m focussing on home front postal censorship, it is important to note that pretty much everything written, spoken, or produced during the First World War was also subject to censorship.

Postal censorship: how it worked

With the outbreak of war in August 1914, the military was placed in charge of postal censorship. In fact the Defence Department had already made tentative arrangements with linguists at various colleges in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin before the August 1914, but nothing had been arranged with the Post and Telegraph Department. There were doubts about the legality of opening people’s mail, but these were put to rest when the Governor, Lord Liverpool, issued warrants under the 1908 Post and Telegraph Act. This allowed the linguists to open and examine outward mail addressed to enemy countries, and people or firms on the Black Lists circulated by the British War Office.

Colonel Gibbon. S P Andrew Ltd: Portrait negatives. Ref: 1/1-013982-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

The Chief Censor in New Zealand was Colonel Charles Gibbon, a British officer on loan from the UK. The tall, thirty-six year old had been dispatched to New Zealand in April 1914. And while the scenery was new, the scenario was not. This was his third Imperial stint, having fought in the Boer War, and served as Staff Captain of the Intelligence Branch in India.

Gibbon’s linguists were initially paid on a piecework basis, receiving payment for each letter or postcard examined. But as the letters rolled in the censors did a roaring trade. Concerned at the considerable sums of money they were making, in October 1914 the military decided to appoint postal officers as the main censors and leave foreign languages to linguists. With salaries set in place, a core team of eight censors took shape. This consisted of a military censor and linguist in Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin respectively, and a team of three in Wellington. Mail was also examined at Devonport, Motuihi, Matiu Somes Island, Nelson Bluff, and in Samoa.

Exactly what censors were meant to be censoring was vague. Writing to the imperial authorities in London for instructions, Gibbon was told there were none. All he had to begin with were British cable handbooks, which stressed the sensitivity of information that could be used by the enemy to jeopardise military operations, such as shipping and harbour reports.

As a result, local censors kept an eye on possible pro-German sentiments and any illegal trading with the enemy. But a few jittery jingoes aside, German espionage in New Zealand turned out to be non-existent. Almost immediately, censorship focused on dissenters who could politically or economically disrupt the war effort: pacifists, socialists, unionists, military defaulters, aliens, certain Māori and Irish, and anyone else ‘with hostile feelings towards the British Empire.’

It is important to note that armed clashes between strikers and special constables had occurred in Wellington less than a year earlier, and in Waihi the year before that. Although an initial wave of nationalism had damped such militancy, the government was always conscious of the potential strength of organised labour. As a result, ‘the correspondence of persons considered desirable to censor’ was included along with information of a military nature.

In November 1914 the outward mail to all neutral countries was added to the earlier warrants, as was any mail addressed to aliens and prisoners of war or internees, inside or outside New Zealand. One of the many War Regulations, gazetted on 17 December and plastered as posters on ships, inside hotels, and other public spaces, informed writers of the surety of imprisonment for evading, obstructing, or interfering with censorship.

As Chief Censor, Gibbon had the ability to recommend the surveillance and arrest of whomever he felt circumvented the War Regulations. However, he was more of a postmaster, directing information into the appropriate hands. Glad to receive such covert intelligence was Sir John Salmond, Solicitor-General of New Zealand from 1910-20 and author of the War Regulations. It was his advice Gibbon sought in many cases, and because of this, Salmond was accused during the 1917 Post Office Inquiry as being the real chief censor of New Zealand.

If Gibbon was the line between agencies, then Chief Deputy Postal Censor Walter Tanner was the hook. A thirty-six year old postal worker, Tanner—like one fifth of Pakeha New Zealanders—was British-born. After his appointment as Deputy in February 1915, it was Tanner who did the bulk of the work. Nothing reached Gibbon or Salmond without crossing Tanner’s desk first. Tanner processed all correspondence forwarded by the regions, compared notes with London, and wrote the quarterly reports held at Archives New Zealand.

Based at Wellington’s imposing General Post Office, Tanner and his fellow Wellington censors were armed with four office tables, five office chairs, a Barlock typewriter, an electric iron, duplicating carbon paper, reams of un-ruled foolscap paper, foolscap envelopes, gummed strips (for resealing opened envelopes), rubber stamps, lead pencils, Banel pens, sheets of blotting paper, iodine, a French dictionary, Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, Kelly’s Dictionary of Merchants, Manufacturers and Shippers of the World, the New Zealand Directory, Wises Wellington’s directory, and a box of pins.

They used this arsenal to impressive ends. As well as sopping all main to and from enemy countries, nationally censors examined over 19,000 letters to and from neutral countries per month. Mail to prisoners of war in Europe was examined at a rate of 930 letters per month, and over 3,000 letters to and from internees in New Zealand were also checked per month.

It is a little wonder that marked men like Charles Mackie of the National Peace Council told his friends not to bother writing. Harry Holland, outspoken socialist and the editor of the Maoriland Worker, wrote that: ‘My letters were held up for periods which ranged from three days to a month… Letters to my wife from our sons in Australia were subjected to the same scrutiny. Even the Christmas cards which came addressed to our children did not escape.’

Although high in volume, this work pales in organisation when compared to other parts of the Commonwealth. By the Armistice in 1918, Britain had 4,861 censors working in the War Office using a systemised registry of suspected individuals. In Australia, censors in six military divisions submitted detailed weekly reports: every bit of information extracted from a letter was typed into spreadsheets, given a unique code, and filed for ease of reference. This greatly aided New Zealand censors, as general mail to Australia was not on Gibbon’s watch-list. Letters were transcribed and sent back across the Tasman, which Gibbon would forward to Police for investigation.

Instead, wartime surveillance in New Zealand was less methodical and more diffuse. A MI5 report on imperial intelligence observed how a Central Special Intelligence Bureau modelled along British lines was never implemented in wartime New Zealand. The military personnel needed for such a branch were all at the front, argued Gibbon, and anyway, the population was so small that ‘everyone appears to know everything about everyone else.’

A Special Branch was eventually set up in 1920 as a direct result of the First World War, becoming the first of many surveillance agencies in New Zealand. But the initial lack of a Secret Service meant Gibbon relied on the close support of the Navy, Customs, the Post and Telegraph Department, the Marine Department, the Aliens Registration Branch, and naturally, the New Zealand Police Force, whose experience of breaking the Waihi Strike of 1912 and monitoring labour agitators put them in good stead for gathering intelligence. The Police Commissioner from 1916 was John O’Donovan, who worked closely with Gibbon to shadow suspects and report on people of interest.

Despite the net in place and the threat of fines or conviction, writers tried to sneak information past a censor’s gaze. Some, like Christchurch bookmaker and antimilitarist Henry Reynolds, hid mail within mail. He was sentenced to three months imprisonment with hard labour.

Others tried spy-like subterfuge. A solution of iodine was used whenever censors came across hints of text written in condensed milk, and letters suspected of using invisible ink were heated with an iron. Just to be sure, selling or buying invisible ink was outlawed in late 1917. Tanner also kept a constant watch ‘for anything suggesting the use of code’ but only ‘a few cases have been detected, all of a harmless nature and decipherable with a little patience.’

Some took postal matters into their own hands. Wharfies and seamen devised an illicit mail network to smuggle letters via the ports, but this slowed to a trickle when the Marine Department increased surveillance in March 1916. Workers weren’t the only ones smuggling mail: in mid-1917, Canadian authorities were tipped off by Gibbon to watch for a Dutch Catholic priest due to arrive in Vancouver. He was stopped, de-robed, and his stash of letters detained. Nurses and soldiers returning to New Zealand with letter-laden khaki also tried their luck. Often they succeeded, only to mail the letters in a country post-office without paying any postage. With no stamps and no sign of being examined by officers at the front, these were easy to spot.

The letters

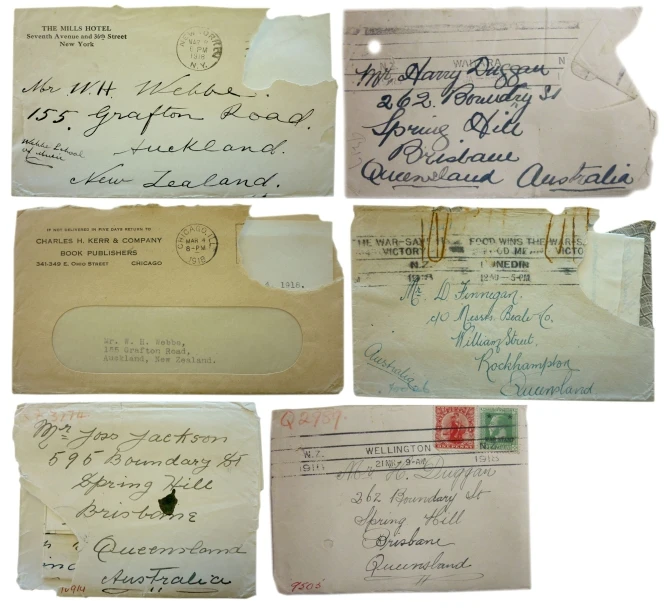

Censorship of correspondence, ‘Secret Registry: Confidential Series’. AD10, Archives New Zealand.

As objects the letters are a real treat. Close to half remain in their original, hand-written form. Some contained treasure within treasure, such as money order receipts from a Te Aro post shop, or pocket-sized pamphlets printed on rebel presses. Others featured elaborate letterheads, patterns of splattered ink, and loose scribbles designed to convey order.

As personal, micro-level stories, the letters at Archives New Zealand highlight the social forces that shaped opinion, and the lenses that people used to make sense of war. They are a useful companion to ‘the generalizations about the macro-level impact of the war on New Zealand society and culture.’ Even the language they used is one way these fragments of everyday life steer us towards a larger and more complex story.

The letters also personalise the debates and figures that existed during the war. The “Shirker”, “Pro-German” or “Dangerous Alien”—figures of abstraction devoid of human needs and emotions—are replaced by real people like Even Christensen, a Scandinavian waterside worker based in Dunedin, or Timothy Brosnan, a loving brother doing time in Roto Aira Prison for his Irish nationalist beliefs.

More importantly (for me at least) the letters also allow us to hear voices often silenced by traditional histories. Most ordinary working-class women and men did not keep diaries, publish their thoughts, or fill the shelves of manuscript libraries with their personal archives. Illiteracy, work-related fatigue, the stress of economic insecurity, and lack of spare time deprived many workers of the opportunity to keep diaries. Letter writing was far more common, yet even these snippets of working-class life are wholly dependent on whether they were kept, or in the case of these letters, if they were detained.

Why were they detained? Analysing the collection shows that they were censored for a number of reasons, from religious objection to perceived anti-British or Pro-German activity. But by far the majority of them were stopped for ideas deemed radical by the government. Indeed, two-thirds of the letters detained and archived in the Army Department’s ‘Secret Registry’ were stopped on political, anti-conscriptionist, or socialist grounds.

According to conscription historian Paul Baker, the government made ‘a small industry’ out of writing War Regulations to suppress opposition. Dissenters like Henry Murphy were punished harshly. Those convicted of publishing information deemed valuable to the enemy were fined amounts up to £10, while anyone who publically criticised the actions of the New Zealand government was fined £100 (close to NZ$20,000 in today’s money) or received twelve months imprisonment with hard labour.

In all, 287 people were charged or jailed during the war for seditious or disloyal remarks under the War Regulations. Per capita this was far greater than Britain, where 422 people of a population of over 42 million were convicted or jailed for sedition under the Defence of the Realm Regulations. However arrests for sedition in Britain were actually lower, as this figure included offences such as evading censorship, spreading false war news, or using fraudulent passports.

It was in this atmosphere of heightened surveillance and class tension that many of the letters in the collection were examined. The issue of conscription naturally found its way into the letters and into the hands of censors.

But censorship continued long after the war came to an ‘end.’ A number of letters date from after the Armistice of November 1918.

As depicted in shows like Boardwalk Empire and Peaky Blinders, the Red Scare of 1919 gave uneasy governments the excuse to increase surveillance and strengthen restrictive legislation. The Reform government extended wartime Regulations into peacetime. Allen believed ‘there was so much lawlessness in the country that the only thing that could save it from going to damnation was the drill sergeant.’

To keep out undesirables, the Undesirable Immigrants Exclusion Act of 1919 was hammered through parliament. This Act gave the Attorney-General power to single-handedly deport anyone who he deemed ‘disaffected or disloyal, or of such a character that his presence would be injurious to the peace, order, and good Government’ of New Zealand. The ink had hardly dried before it was used to deport Moses Baritz, a touring lecturer from the British Socialist Party. Packed up and shipped to Sydney, Baritz was one of many deported from New Zealand during the 1920s.

Censors were also kept at their posts. Allen wrote to Massey in July 1919 that ‘a good deal of valuable information comes to the government through the medium of the censor, and it was thought wise not to lose this information.’ Tanner stayed on as Deputy Chief Postal Censor, and when Gibbon left New Zealand in June 1919, he forwarded most censored mail to Salmond. As late as October 1920, labour leaders like Harry Holland and Ted Howard were complaining in parliament that mail was still being opened.

Yet by 1920 the peak of postal censorship has passed. By that time the Special Branch was in full swing, having set up a detailed card index on radicals and their activities. The War Regulations Continuance Act was also introduced, which was not repealed until 1947. Through these means, the relatively ad-hoc system of wartime surveillance was systemised, and large-scale censorship was no longer needed. On 16 November 1920—six years and over a million letters later—the censorship of private correspondence officially came to an end.

‘Don’t let your hubby see this’: Frank Burns to Miss D Nugent

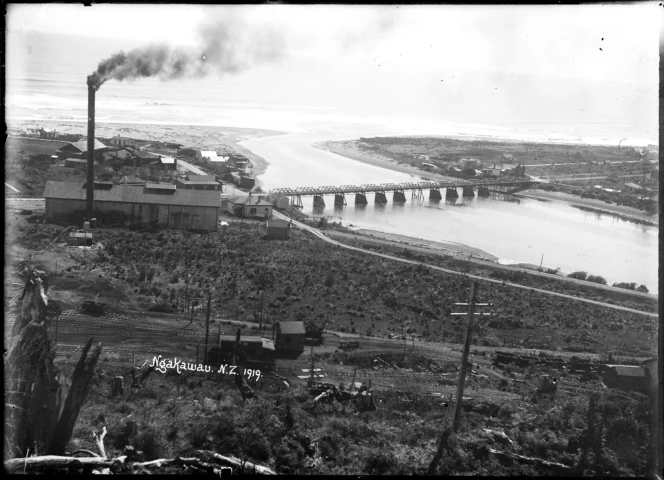

Ngakawau, Buller district. Radcliffe, Frederick George, 1863-1923: New Zealand post card negatives. Ref: 1/2-006439-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

With this overview in mind, I want to share one of the censored letters in the collection. It is a letter that gives an insight into someone on the margins of wartime society—a deserter from the military. His name was Frank Burns, aka Frank Lonnigan.

Frank was a West Coast miner on the run from conscription. The 21-year old had been hiding out in the bush, where he wrote this letter to an ex-sweetheart living in Australia. It was stopped by the censors and given to police, who finally tracked and arrested Frank as a military defaulter. He was sentenced to two years in prison. His letter never reached Miss Nugent (or her hubby): it remains in its original envelope at Archives New Zealand.

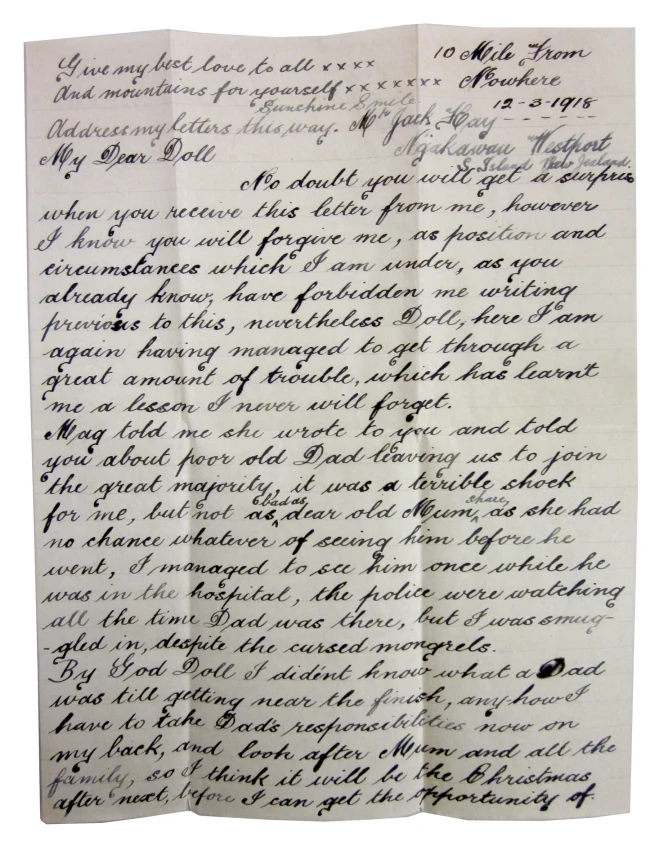

10 Mile from Nowhere (Ngakawau, Westport), 12-3-1918

My Dear Doll,

No doubt you will get a surprise when you receive this letter from me, however I know you will forgive me, as position and circumstances which I am under, as you already know, have forbidden me writing previous to this, nevertheless Doll, here I am again having managed to get through a great amount of trouble, which has learnt me a lesson I never will forget.

Mag told me she wrote to you and told you about poor old Dad leaving us to join the great majority, it was a terrible shock for me, but not as bad as dear old Mum as she had no chance whatever of seeing him once he was in the hospital, the police were watching all the time Dad was there, but I was smuggled in, despite the cursed mongrels. By God Doll I don’t know what a Dad was till getting near the finish, anyhow I have to take Dad’s responsibilities now on my back, and look after Mum and all the family, so I think it will be the Christmas after next before I can get the opportunity of seeing you again, which I know will not be as much joy as I anticipated when meeting you again, that is if what I hear is true. Well Doll, rumours are circulating here to the effect that you have undertook to yourself a husband, cannot believe it myself, but if such is the case remember there is a lad here, waiting to serve you in anyway you like to mention also that all the good luck and happiness that is possible to get, be bestowed on you and the hubby.

Well kid, I had an idea you were going to wait for me, Christ knows where I got the notion from, and I haven’t lost it yet. I will wait until your hubby is pushing the daises up, and then arrive and claim you. I will love you all the more when the silver threads are shinning in your dear old barnet-fair.

Anyhow Doll I suppose you would have nothing to do with me now, if you wasn’t married, I can’t see you having any time for a military evader or shirker old kid. My God it gave me a bump when I heard you were married, but I’ve got no objections, so go for your life and get all the enjoyment possible to get.

Well old dear my Christmas festivities were the most troublesome and disappointing ever I experienced so far, not like the previous one kid, when we got together roaming those hills. The one when you was here was all fun and frolic, and this one all sorrow and sadness, so you can imagine what it was like, just the two extremes. What do you think of those policemen, it tells you what they will do, when they watch a man’s father on his deathbed and also his funeral to try and capture his son for evading and refusing to go and fight their cursed wars.

I heard that Johnson {one of your associates I’m sorry to say} has gone to the war, and I sincerely hope that he gets shot right in the bottle and glass and get blown right out of existence. Hope you take no offence at that way I explain things, but if you was here, you would probably hear worse that that, the experience I have been through has made my heart hard and bitter against those mongrels of humanity.

This present position I am obliged to be owing to Gawd’s Own Government could have been avoided in numerous ways, but it seems that fate destined to place me here. You remember me telling you about old Porky applying for my exemption, well he commanded it alright, and a month after, me and the bumptious old buggar had an argument, so I lifted my time and left, like a fool. Well next exemption board they wanted to know my whereabouts, and old Porky told them I was at Waiuta, so that was alright but after finding out I wasn’t there, they issued orders to proceed to camp, which I did, only in the wrong direction, I went to the camp in the bush instead, where I am going to remain for a while yet.

Well kid I wanted to go to Waiuta but Dad said stop here, so the next item was to proceed which I done to perfection. So you can see Doll old darling what the little bit of hot-headedness of mine will do, you know that little bit, you used to always be lecturing me, and giving me advice about. I wish I had taken a bit of notice of you then, kid, but I never, so you can see the position it partly landed me into today. Say Doll how is poor old Glycerine getting on, had she been wearing those new-fashioned skirts again yet, you know those ones that is up in the front, and down at back.

How is little Sylvia and Minnie getting on when you see them again, give my best love to them, also tell them I received that letter of theirs, and explain to them why I can’t write, but will as soon as possible. Give my best love to your dear old mum, and ask her if she has got another daughter like you she can give me as you are married, if she hasn’t tell her to give your hubby the boot so as to give me another chance. God Bless her dear old Irish heart, and tell I hope that old Ireland never runs short of murphys {spuds}. How is brother Pat the champion snap-grabber getting on.

Well Doll old darling I’m getting a bit cheeky, when I started this letter I said to myself I won’t put any ‘darlings’ and ‘dears’ in it, because your hubby might see it, but buggar it kid this is the only way I can talk to you {Damn it, you know I love you}. I say kid I received those photos of you and Rose, and by Christ, they were sniffters also that Christmas card, and you can just imagine how sorry I was not being able to send you one, anyhow I got all those keepsake’s of yours, and I hope you have got mine.

Well Doll old darling, you know how I can’t mention no names, in case this letter is opened, but the last time I heard from goat-gulley everything was pie on the kittens-kidney. I believe young “Bum” is growing in fine stile, and my little horse-rider is well, so things are pretty good as far as health goes. Well kid this life of mine is getting very monotonous but I’m determined to carry it through, use the utmost discretion when addressing my letters, and don’t put my name on the envelope, and for Christ sake don’t let your hubby see this, burn it, so I will conclude Doll with fondest love From your old has-been. Frank Lonnigan. xxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Censorship of correspondence, Frank Lonnigan to D Nugent, April 1918 - May 1919. AD10 Box 10/ 19/4, Archives New Zealand.

The impact of postal censorship

Despite its military beginnings, the letters in the collection suggest the net put in place by the state was politically motivated, far-reaching, and although smaller and less streamlined than Britain or Australia, generally successful in its self-directed aims. Censorship ensured the authority of those in power remained in place during what was a remarkably volatile time.

It is important to note however that total censorship—the checking of every letter ever posted to, from, or within New Zealand—was never introduced, although War regulations in mid-1918 gave the military the power to do so. Of course, knowing that unintended eyes would be reading their letters meant writers self-censored genuine feelings for fear of infringement. But not all examined letters were kept or destroyed. The majority reached their intended readers, having been stamped ‘Passed by the Military Censor’. In some cases lines were simply blacked out or returned to the sender complete with friendly advice.

Yet the scale of postal censorship—the sheer amount of personal stories each censor was privy to on a daily basis, and their ramifications—should not be underestimated. The state invasion into people’s thoughts and opinions had material and long-lasting effects.

Of the seventy-four Secret Registry letters, twelve went no further than its Defence Department file. But most sparked some form of police surveillance, ranging from a chat at the door to covert shadowing. What happened next varied. Maria Weitzel, a German-born Wellingtonian, was forced to report weekly to police on account of her mail, and if she wanted to travel outside of the city she needed a permit to do so. Challenged by her gender and sexuality, the military subjected Hjelmar von Dannevill to a forced medical examination to determine her sex, and then interned her on Matiu Somes Island. Philip and Sophia Josephs had their home (of eight children) raided, while others were arrested, interned, or deported. Wary of critique and confronted by difference, those in power used it to protect that power. And although it was not as devastating as the death of a loved one on the battlefield, the heavy hands of the censors still disrupted the lives of many.

The lasting impact of the First World War on New Zealand society is well known. Kate Hunter and Kirstie Ross note how ‘the Great War seeped and stormed into New Zealanders’ lives and could not be easily or quickly dislodged at war’s end.’ As archives, the letters herein are the tangible evidence of this.

But postal censorship during the First World War not only created archives. It helped to cement the role of surveillance in monitoring dissent for years to come, both in legislation and in the form of the Special Branch. The NZSIS, GCSB and other agencies all trace their origins back to O’Donovan’s Special Branch. Like the phenomenon of ‘disaster capitalism’, the turmoil of 1914-1918 served to expand and make permanent measures introduced at a specific time, for specific reasons. We only have to read the news to see that one hundred years on, the five eyes of Tanner, Gibbon, O’Donovan, Salmond, and Allen are still with us—albeit in more advanced forms.

Jared Davidson delivering the lunchtime talk on which this transcript is based. National Library, July 2015. Photograph: Mark Beatty.

Rae Reynolds ,as soon as I saw that name I immediately thought of you as a family connection and was going to share to you but I see you've already responded ....wouldn't Hackey and Francis be so interested in this