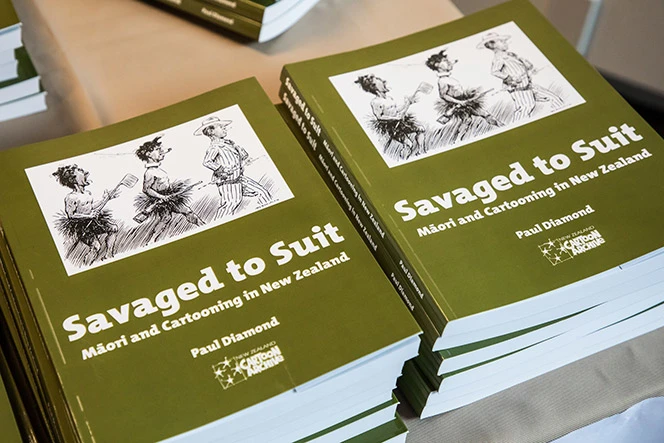

Launch of 'Savaged to Suit: Māori and Cartooning'

On September 25th 2018, Paul Diamond’s ‘Savaged to Suit: Māori and Cartooning in New Zealand’ (1) (Fraser Books) was launched at the National Library by Louisa Wall, MP for Manurewa. The book was written for the New Zealand Cartoon Archive, as part of a series about cartoons as an historical source. Here we reproduce the address by Paul, with accompanying cartoons and photographs of the event.

Savaged to Suit: Maori and Cartooning in New Zealand. Photo Mark Beatty.

Sir Gordon Minhinnick, has been described as the pre-eminent New Zealand cartoonist from the mid-1930s through to the ‘60s. It’s not surprising then, that he looms large in a historical study of editorial cartoons about Māori and their culture, focusing on the 1930s up until the 1990s.

Minhinnick argued the function of a cartoon is essentially critical, and described cartooning as a destructive medium. He also had a warning for anyone attempting to understand the history of NZ through editorial cartoons:

"A cartoon is a negative conception, it is usually against something or somebody. Thus the history of a country seen through cartoons of the period may have an inherent imbalance."

Implicit in this is the idea of a line dividing what’s deemed acceptable. Minhinnick's career illustrates how this line has shifted over time.

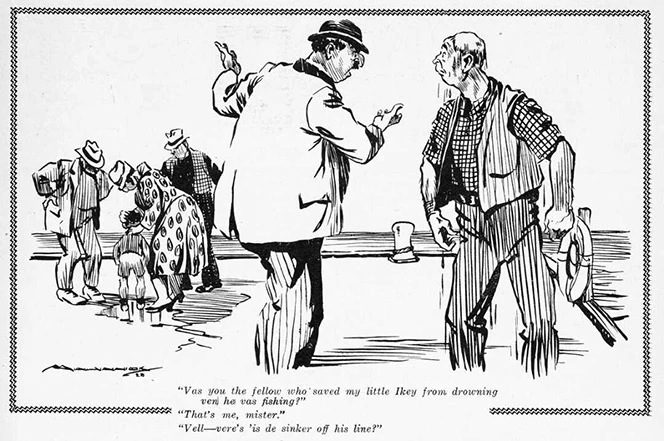

Up until the mid-1930s, racist cartoons were more common in this country. For example, a Minhinnick cartoon from 1929 where a Jewish father of a small boy interrogates the rescuer, while in the background three people look after the boy. I’m showing this cartoon to give context for the cartoons about Māori, which also featured negative racial stereotyping.

Cartoon by Sir Gordon Minhinnick, 1902-1992, 'Vas you the fellow who saved my little Ikey from drowning ven he vas fishing?'... New Zealand Artists' Annual, 1929. Ref:A-311-1-007.

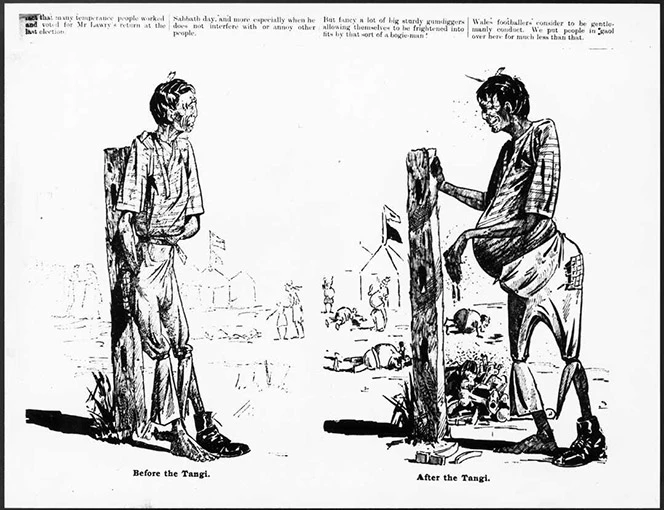

For example, an 1894 cartoon by an unknown artist featuring a Māori man before and after a tangi

The man has been drawn with some of the signifiers commonly used to represent Māori by cartoonists: bare feet, or wearing one shoe; dishevelled clothing; and one or more tail feathers from the Huia bird.

New Zealand observer and free lance (Newspaper). Cartoonist unknown :Before the tangi. After the tangi. New Zealand Observer and Free Lance, 13 October 1894. Ref:J-065-020

After 1935, Ian F. Grant has argued, there was little in cartoons about race relations, ‘…partly because the worst abuses had been outlawed, but also because there has been an increasing unwillingness to satirize race relations.’ (2) In Savaged to Suit, I argue that stereotyping of Māori in cartoons continued, but in different ways.

Māori regularly appeared in traditional dress as comical figures of mirth or derision. For example, the ‘Little Brown Mandate’ figure created by Minhinnick, after Labour won the 1946 election by four seats, which he and other commentators decided were the four Māori seats. The figure was part of the media criticism of the so called ‘Māori Mandate’ following the election.

Minhinnick’s first cartoon on the subject appeared two days after the election and depicted a tiny man in a business suit walking into Labour’s offices and announcing ‘Morning Boys – I’m the new mandate!’ The second, published a week later, depicted the figure shrinking and turning into a Māori, as Peter Fraser and other shocked Labour MPs look on, exclaiming, ‘Oo, Look! He’s shrinking and turning brown!’ (3)

Another example, published just weeks out from the 1949 election (4) depicted Fraser holding up the tiny figure in triumph in 1946. By 1949, as Tiopira McDowell has noted, the mandate had become a giant, overweight and sneering Māori, who seemed to be crushing the life out of Nash, much to the surprise of an on looking journalist.

What did Māori think of cartoons like these? There's little recorded, but there are several interesting pieces of evidence.

The first is commentary by the Ngāti Ranginui anthropologist and leader, Maharaia Winiata.

The Little Brown Mandate, wrote Winiata, was the expression of the stereotypes ‘generally applied by an in-group majority to an out-group minority, ascribing undesirable qualities in a situation of tension ... The Maori was lazy, improvident, lived off the European, and was over-indulged by a Labour Government’. Winiata ‘remonstrated with Minhinnick on the severity of ridicule aimed at the Māori people in his cartoons, and for a period ‘Little Brown Mandate’ took a holiday’, but continued to appear in the New Zealand Herald until the cartoonist’s retirement in 1976.

My other example is a stereotype illustrated by cartoons which appeared in a series of books published in the 1960s by ‘Hori’. ‘Hori’ was the pseudonym of Wingate McCallum, a New Zealander of Scottish descent based in Remuera, ‘who claimed he had countless friends among the Maori people’ and that his ‘admiration of the first New Zealanders is unbounded’. McCallum wrote stories about a Māori man, Hori, who has adventures with the Pākehā coot up the street, goes to the races, argues with his mother-in-law and has opinions about politicians.

The stories were collected in book-form in The Half-Gallon Jar in 1962 with illustrations by Frank St. Bruno. The book was hugely popular and was followed by three further collections over the next ten years. The stories illustrated the stereotyped views, as summarised by John Rangihau in 1963 ‘which see (from the Pakeha side) all Maoris as lazy and unpunctual, and (on the Maori side) all Pakehas as cunning go-getters who would do you down for tuppence’,

Noel Harrison has argued that ‘Humourists and cartoonists did more than politicians or officials to shape racial perceptions. While few people read the Hunn Report on the state of Maori in 1960, many thousands laughed at the character named Hori, who came to represent one persistent stereotype of Maori. (5)

The move away from this sort of representation is a major theme of Savaged to Suit. This came about because of several factors. One is the emergence of a generation of cartoonists whose views weren’t necessarily aligned with those of newspaper editors and proprietors.

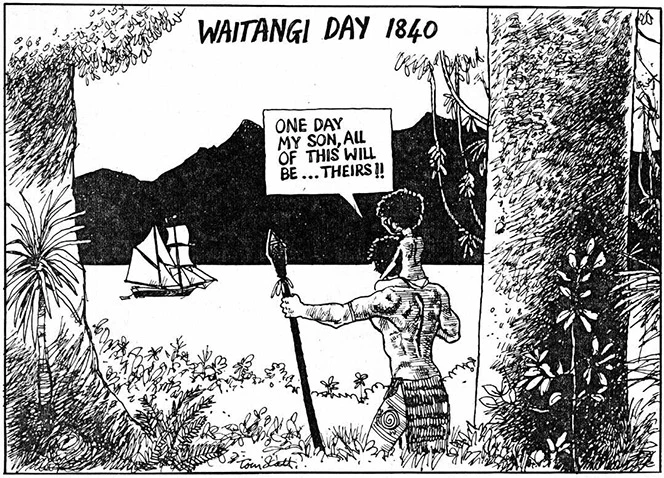

For example, Tom Scott. Here’s one of his cartoons from Waitangi Day in 1988 imagining the day in 1840.

Cartoon by Tom Scott, 'One day my son, all of this will be ... theirs!!' Evening Post, 5 February 1988]. Ref:H-733-061

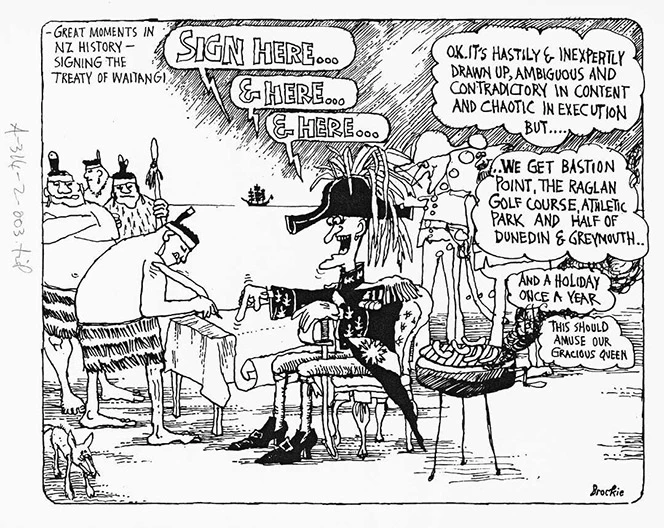

Bob Brockie also used Waitangi Day in 1840 as the starting point for a cartoon about how the national day and the Treaty were seen in 1982.

Cartoon by Bob Brockie. Great moments in N.Z. history — Signing the Treaty of Waitangi ... National Business Review, 8 February 1982. Ref: A-314-2-003.

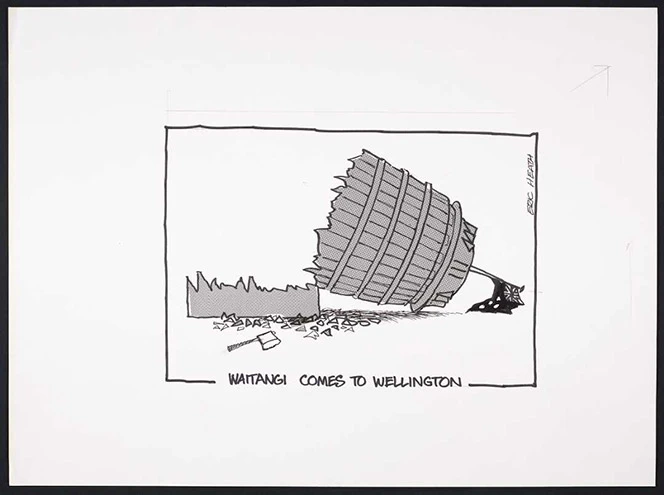

And Eric Heath, who produced this response to the 1985 decision to allow Treaty claims back to 1840.

Cartoon by Eric Heath, Dominion Post. Ref: B-145-536

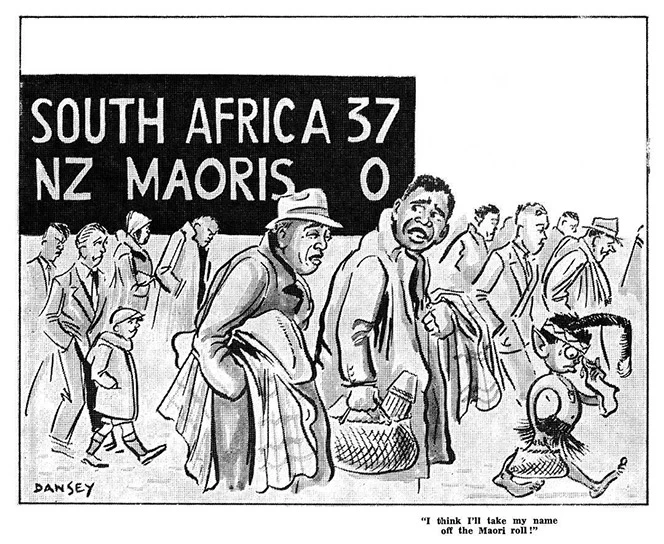

The book also looks at the contribution of the small number of Maori cartoonists. These include Harry Dansey, who produced cartoons for the Taranaki Daily News in the 1950s

and Anthony Ellison, from Ngāi Tahu, whose cartoons appeared over a 13-year period, making him the Māori cartoonist with the longest publication history.(6)

Cartoon by Harry Dansey I think I'll take my name off the Maori roll! Taranaki Daily News. Ref:J-065-068

The other reason representation changed is the resistance, at certain moments, by Māori. One of these moments was the 1979 protest against the ‘haka’ performed by Auckland University Engineering students, known as the Haka Party incident. A representative from He Taua, the group claiming responsibility for the attack, told the NZ Herald ‘He Taua was protesting at the way the student haka party was turning Māori culture into a racist cartoon to be laughed at’.

Closer to our own time, another moment of resistance to the representation of Māori cartoons was the case taken by Louisa Wall (7) to the Human Rights Review Tribunal and the High Court, over two cartoons by Al Nisbet depicting Polynesian families.

One of the cartoons showed a group of adults, dressed as children, eating breakfast at school and saying

"Psst . . . If we can get away with this, the more cash left for booze, smokes and pokies". (8)

The other showed a family sitting around a table littered with Lotto tickets, alcohol and cigarettes and saying

"Free school food is great! Eases our poverty and puts something in you kids' bellies". (9)

While the judge in the High Court described the cartoons as 'offensive' and 'inappropriate,' they were found not to be in breach of the Hate Speech provisions of the Human Rights Act. Nonetheless, Canterbury University Law School Dean, Ursula Cheer, said the decision gives important direction, and is a reminder that in cases like this, people should speak out. 'The idea is that more speech is better than no speech' (10). The case remains an important example of one of the key themes of this book: resistance to stereotyping. Which was why we asked Louisa to launch the book, and we’re very grateful she agreed to do this.

These moments of resistance keep happening. There was one recently to do with a cartoon in an Australian paper of the tennis player, Serena Williams. Writing about the row in the Guardian, Gary Younge said

'…we should never be in denial that there is a line and only some people get to draw it.' (11)

Which brings us back to my initial comments about how Minhinnick’s cartoons illustrate the shifting line for what’s acceptable in cartoons. To see this, you need to critically read cartoons and study them as historical sources. This runs counter to the cartoonist Peter Bromhead's description of cartoons as

‘instant comments, momentary food for thought .... There’s certainly nothing as dead as yesterday’s cartoon.’ (12)

Savaged to Suit is one big argument against that.

I'm grateful to Ian F. Grant for asking me to be part of the series aiming to illuminate the history of cartooning in New Zealand. I'm also grateful to my boss, Chris Szekely and the whole talented team here at the Turnbull and National Libraries who helped me produce the book, together with my friends, family and colleagues. Thanks to Ian, Diane and the team behind Fraser Books for producing the book we're sending into the world tonight.

Kathryn Ryan, thank you for MCing this evening, and thank you all, for being here to support this kaupapa.

E ai ki te korero, ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi, engari, he toa takitini.

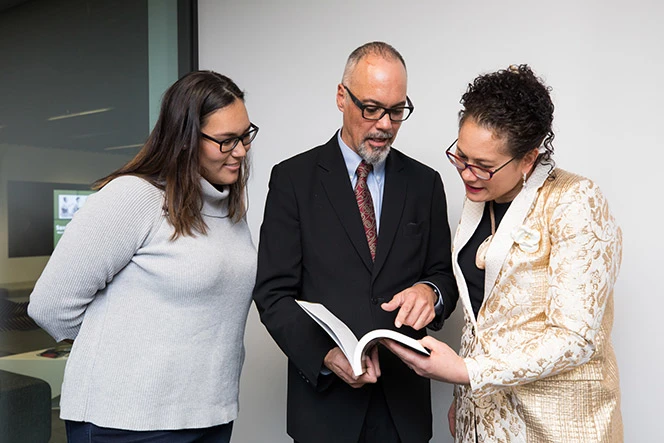

Ella Diamond, Paul Diamond and Louisa Wall at the launch of

Savaged to Suit: Maori and Cartooning in New Zealand

The book was launched by Louisa Wall and is dedicated to Ella Diamond, the author’s niece. Photo Mark Beatty

Links to coverage in media and social media about Savaged to Suit

Endnotes

The Unauthorized Version : A Cartoon History of New Zealand, Ian F. Grant (1987), p.5.

“Oo, Look!”, Gordon Minhinnick, NZ Herald, 9 December 1946.

The Oompah Games, Gordon Minhinnick, NZ Herald, 1 December 1949

Graham Latimer : a Biography Noel Harrison (2002), p.165.

Stuff — Labour MP Louisa Wall takes Fairfax to High Court over 'offensive' cartoons

RNZ — Disparaging cartoons of Polynesians 'not illegal' - High Court

The Guardian — The Serena cartoon debate: calling out racism is not ‘censorship’

The Unauthorized Version : A Cartoon History of New Zealand, Ian F. Grant (1987), p. 234