He kupenga hao, he waka huia

Celebrating today's 50th anniversary of the Māori language petition the Turnbull Library Curatorial Services team have selected examples of Māori language taonga cared for by the Library to illustrate Aotearoa's journey of revitalisation of te reo Māori.

He kupenga hao, he waka huia

Writing in 1893 to Dulau & Co, a London bookseller, 24-year-old Alexander Horsburgh Turnbull spelled out his intention for his collection:

anything whatever relating to this Colony, on its history, flora, fauna, geology and inhabitants, will be fish for my net, from as early a date as possible until now 1.

Te reo Māori was a central part of this declaration. We know from the archival record, for example, that Turnbull was already collecting Māori material at least two years before this, as he wrote to his brother Robert listing relevant books purchased:

He pukapuka Aroha: pa te Aroha pono: No 1 Aug, 1837. Printed at Paihia at the Missionary Press. He Korero Kohikohi enei no te Kawenata Tawhito: Mangungu 1840. And a little book printed in double columns of scripture extracts prayers & hymns, without title page and not described in Sir Geo. Grey’s catalogue. I have also obtained the first edition of Maunsell’s Maori Grammar (sic), in the original 4 parts, with the original covers. And another little work in Maori of Scripture Extracts & Hymns printed in New Zealand at the Wesleyan Missionary press in 1837. These I think must be fairly rare. 2

Such material was not only sourced from overseas booksellers like Dulau, but also locally with the help of a network of advisers, including Bishop Herbert William Williams. HW Williams was the grandson of Bishop William Williams, who compiled an early Māori-language dictionary published in 1844.

Today the printed Māori collected by Turnbull and by the Alexander Turnbull Library from 1918 onwards is being digitised as part of the Books in Māori/Ngā Tānga Reo Māori digitisation project.

This invaluable work is making these texts available to researchers the world over via the Papers Past website as a resource for the revitalisation of the language.

As the country marks the 50th anniversary of the Māori language petition, the Turnbull Library Curatorial Services team have selected examples of Māori language taonga cared for by the Library, building on Turnbull’s legacy and highlighting some of the resources available with an eye towards future research and in support of te reo Māori.

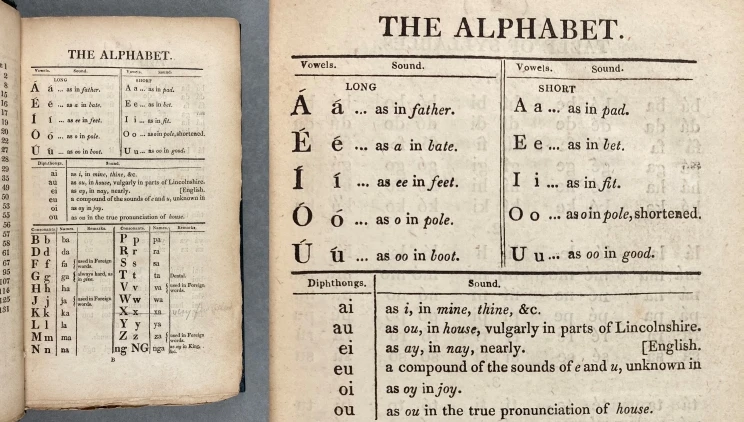

A grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand

While the earliest appearance of te reo Māori in print is found in John Hawkesworth’s Account of the voyages undertaken … for making discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere (1773), it was not until the arrival of the first missionaries during the early nineteenth century that a serious attempt was made to lay down the fixed principles of the Māori language.

The missionary tasked with this undertaking was Thomas Kendall, who arrived in Aotearoa in 1814. Drawing heavily on the knowledge of the Ngare Raumati rangatira Tuai — who taught Kendall the rudiments of the Māori language — and other Māori in the Bay of Islands, he compiled the first Māori-English primer, A korao no New Zealand. Around 200 copies were printed in Sydney in 1815 of which only a single original copy survives, held by Auckland Museum.

This early enterprise was expanded upon when, in March 1820, Kendall accompanied the Ngāpuhi rangatira Hongi Hika and Waikato to England. While there they collaborated with the linguist Professor Samuel Lee at Cambridge University, utilising material collected by Kendall not only from Tuai, but also Titere, who visited England with Tuai in 1818, and from other Māori. Their efforts were published later that year as A grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand, which was much more widely distributed than the 1815 primer.

Thomas Kendall, A Grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand (proof copy), 1820. Alexander Horsburgh Turnbull bequest, 1918. Ref. MSX-5213.

The text consists of an alphabet, an orthography, a Māori-English vocabulary list of 2,000 words, waiata, and translations of prayers and dialogues. It was issued in two versions: 250 copies on fine paper, mainly for circulation in England to spark interest in the work of the Church Missionary Society, and another 500 copies on coarse paper for use in Aotearoa.

Of far greater importance, however, is the indispensable role Māori played in its compilation. Their teaching and knowledge sharing are imbued within its pages, making it a true privilege to hold a copy of the book in one’s hands.

— Anthony Tedeschi, Curator Rare Books and Fine Printing

Tuai and Titere

The two portraits below by James Barry, painted in 1818, are of Tuai and Titere who were among the earliest Māori to travel to England, and who had great influence in shaping the European understanding of Māori culture and language.

The two portraits were painted in London for the Church Missionary Society (CMS), the artist James Barry being a lay member of the CMS. Tuai and Titere left New Zealand, travelling first to Australia, before embarking on a voyage to England with the CMS in 1818. They returned to New Zealand in 1819, but their portraits remained in London, hung in the premises of the CMS until their acquisition by the Alexander Turnbull Library in c. 1920–1930.

James Barry, artist. ‘Tooi (i.e. Tuai), A New Zealand chief’. October, 1818. Ref. G-608. Alexander Turnbull Library.

The calm and dignified faces of the sitters reflect the importance that these two men played in introducing Māori culture to the world. We are presented with two individuals who are dressed as English gentlemen. Knowing their connection to the CMS could belie us to believe that they were early converts to Christianity.

James Barry, artist. ‘Teeterree (i.e. Titere), a New Zealand chief’. October, 1818. Ref. G-626.

It is only through their letters and accounts that we can more deeply understand the complexity of their relationship with the CMS, and with Mātauranga Māori. Alison Jones and Kuni Jenkins in their text He Korero, Words Between Us, First Maori-Pakeha Conversations on Paper (2011) reveal that, ‘Both men refused to become the Europeanised figures of the missionary civilisation fantasy’ (p. 159). In this way we come to understand that what James Barry has painted limits our understanding of these men. The portraits themselves could be understood as the expression of the CMS, how they wanted the world to view Tuai and Titere.

As curators in the twenty-first century, we cannot necessarily understand their mana Māori and what this meant to them, but we can celebrate them as two figures who strived to honour Mātauranga Māori, and gift this knowledge to the world.

— Apryl Morden, Assistant Curator

Hoea Rā te Waka Nei

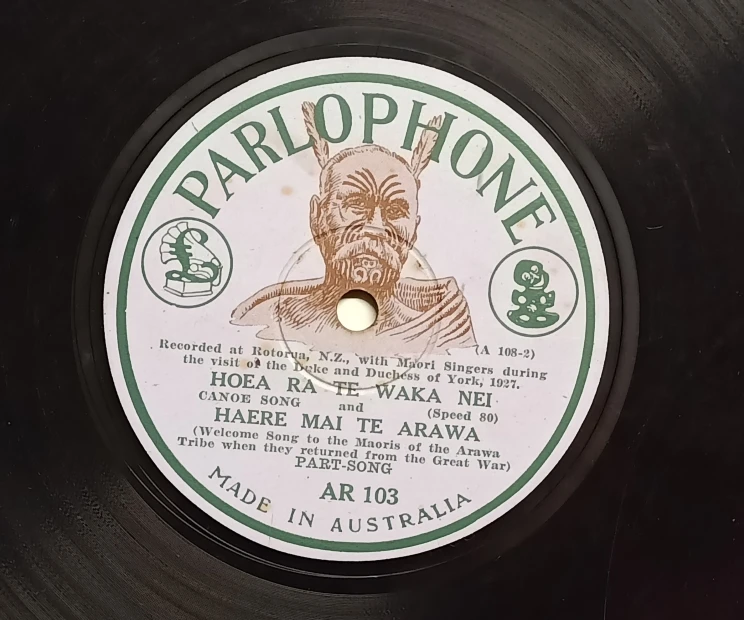

Te reo Māori featured prominently in the first commercial sound recordings made in New Zealand. A concert party was recorded performing haka, and waiata in Māori and English for the Duke and Duchess of York during their visit to New Zealand in 1927. The recordings feature Ana Hato (Tūhourangi, Ngāti Whakaue) and her cousin Deane Waretini (Tūhourangi). Released as eight double-sided discs, these were recorded in Rotorua by the mobile unit from the Australian branch of Parlophone.

Hoea Rā te Waka Nei (Canoe song) and Haere Mai Te Arawa, sung by Ana Hato with chorus. Ref: Phono q3532.

One waiata Hato sings is Hoea Rā te Waka Nei, which she combines with Haere Mai Te Arawa. The latter welcomes back soldiers of Te Arawa iwi returning from World War I. A First World War memorial in Rotorua to the Arawa people was unveiled during the visit of the Duke and Duchess.

Recording of Hoea Rā te Waka Nei’ (Canoe song)

Hoea Rā te Waka Nei (Canoe song) and Haere Mai Te Arawa, sung by Ana Hato with chorus. Ref. Phono q3532

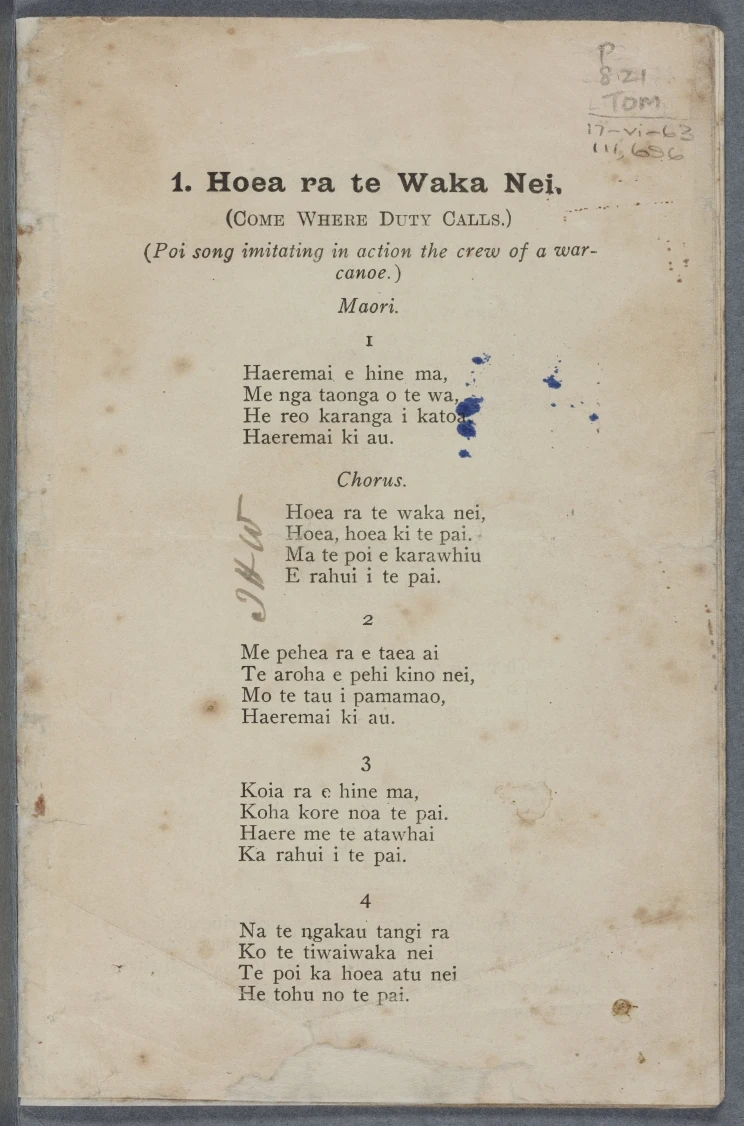

Hoea Rā te Waka Nei was composed during World War I by Paraire Tomoana (Ngāti Te Whatu-i-āpiti, Ngāti Kahungunu). Performed as a seated poi, this “canoe song” was part of fundraising concerts for the Māori Soldiers’ Fund. The text was published in a booklet prepared by Tomoana and Sir Apirana Ngata (Ngāti Porou) — A Noble Sacrifice — and sold also as a fundraiser. The metaphor of paddling a waka (Hoea rā te waka nei) urges the audience to support troops overseas. Proving popular, this booklet was reissued with four additional songs in 1921.

The first page of the reprinted version of A Noble Sacrifice. Hoea ra te waka nei = Come where duty calls / words and action arranged by Hon. A.T. Ngata and P.H. Tomoana. Ref. P Box 821 TOM 1921.

By the time Hato performed for the Duke and Duchess, Hoea Rā te Waka Nei had already been published as sheet music by Arthur Eady in 1926. Combined with Pōkare Kare in this publication, both songs had been arranged by Hemi Piripata (pseudonym for James Henry Phillpot). Further recordings of Hato and Waretini, including a new recording of ‘Hoea Rā te Waka Nei’, were made by Parlophone in Sydney in 1929.

— Keith McEwing, Assistant Curator Music

Ko tōku tūrangawaewae ko tōku mana | Knowing my place in the world is my source of strength

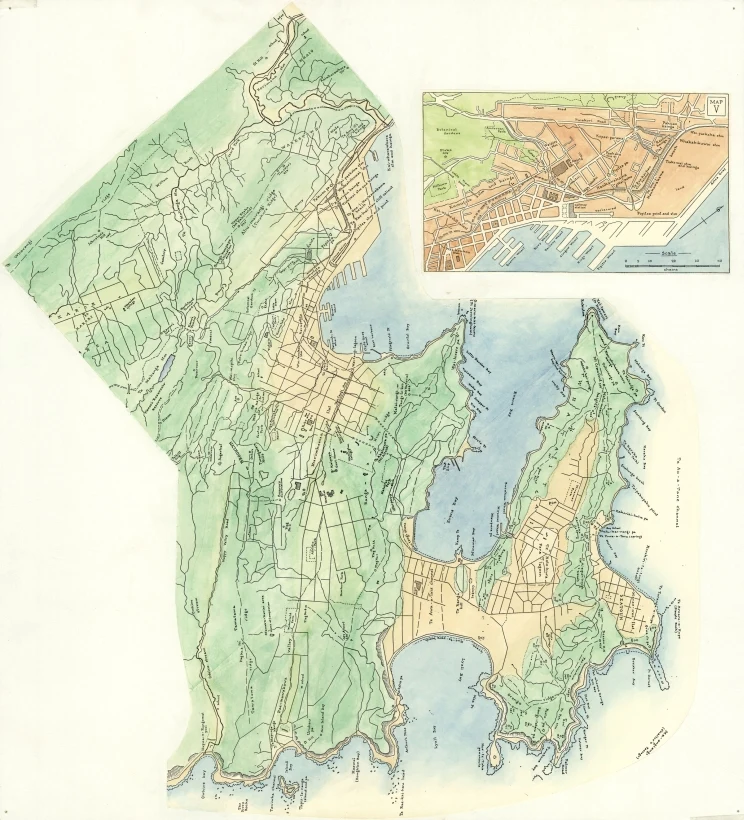

One of the principles that shape and drive the work of New Zealand Geographic Board Ngā Pou Taunaha o Aotearoa is kaitiakitanga, signified by the Board’s dedication to preserving and protecting New Zealand’s heritage through place names. It acknowledges the mana of places, tangata whenua and other communities through collecting, recording the stories of, and making official the original Māori place names. This important work is often augmented by maps, whether they are used as a source of information or a conduit of mātauranga Māori and Te Reo Māori.

Alexander Turnbull Library’s cartographic collections contains 397 maps and charts generously donated by the Board in 2014. They were part of a working set used by the Board in their mahi | work containing annotated published maps, facsimiles of early maps and charts, and a few manuscript maps produced or created collectively between the 1860s and the 1990s.

Ko tōku tūrangawaewae ko tōku mana | Knowing my place in the world is my source of strength 3

Adkin’s map of Wellington with Māori place names

A facsimile copy of George Leslie Adkin’s manuscript map of Wellington, with Māori place names drawn circa 1950, depicts the geographic and cultural landscape of the city. The original map is hand drawn, with fluid, delicate colouring, a dense network of streams and markings of Māori kainga, pā, tracks, cultivation areas, and original place names.

Facsimile copy of a manuscript map of Wellington with Māori place names attributed to George Leslie Adkin, ca. 1950. Ref. MapColl-NZGB-4/22/292/Acc. 54978. Alexander Turnbull Library.

The map also contains contemporary features, such as street networks, reclaimed land areas, the shoreline at that time, and a few European place names for geographic context.

By featuring placenames and areas of cultural significance to the local tangata whenua (Te Atiawa), the map reminds us of the significance of time, place, and memory – ngā kōrero tuku iho – and the enduring mana of tangata whenua. For example, the place names Tiakiwai, Te Ahumairangi and Pipitea are used for different areas in the National Library building as it sits either on or near these places which are of cultural significance to the mana whenua.

— Igor Drecki, Curator Cartographic and Geospatial Collections

— Sheena Tawera, Librarian, Arrangement and Description Team

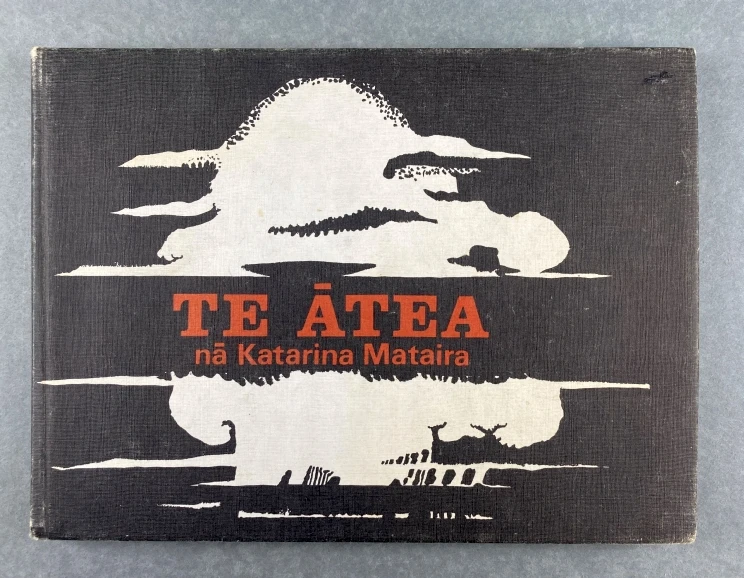

A science fiction novel in te reo Māori in verse form

Dame Kāterina Te Heikōkō Mataira (1932–2011), was the author of the first novel in te reo Māori. She was raised by matua whangai who did not speak English in an immersive Māori world. Writing, education, teaching, mahi toi and the struggle to retain and revive the Māori language were just some of the items in her kete. Countless students have participated in the Ataarangi language program she established with Ngoi Pewhairangi. Kura Kaupapa Māori and the Māori Language Commission were language initiatives that drew upon her skills and strengths.

Pungarehu anaake te ao – the world is nothing but ash!

Te atea: na Katarina Mataira; ko nga pikitia na Para Matchitt. Wellington: School Publications Branch, 1975. Ref. Fomison MAT 1975.

Te Ātea was first published 47 years ago and the themes are prescient in this age of planet wide climate change and the outbreak of pakanga. The drawings are by one of the early practitioners of contemporary Māori Art and her contemporary, Para Matchitt. The words and sentences are deceptively simple and repetitive and like cuiseniare rods are moved around to form new sentences and duplicate them for language reinforcement. English translations are provided for some phrases. Mataira said in an interview, ‘Papaku te reo, he kaupapa tino nui.’ Te Ātea was edited and republished in 2021.

— Geraldine Warren, Curator New Zealand and Pacific Published Collections

Kia kaha te reo Māori

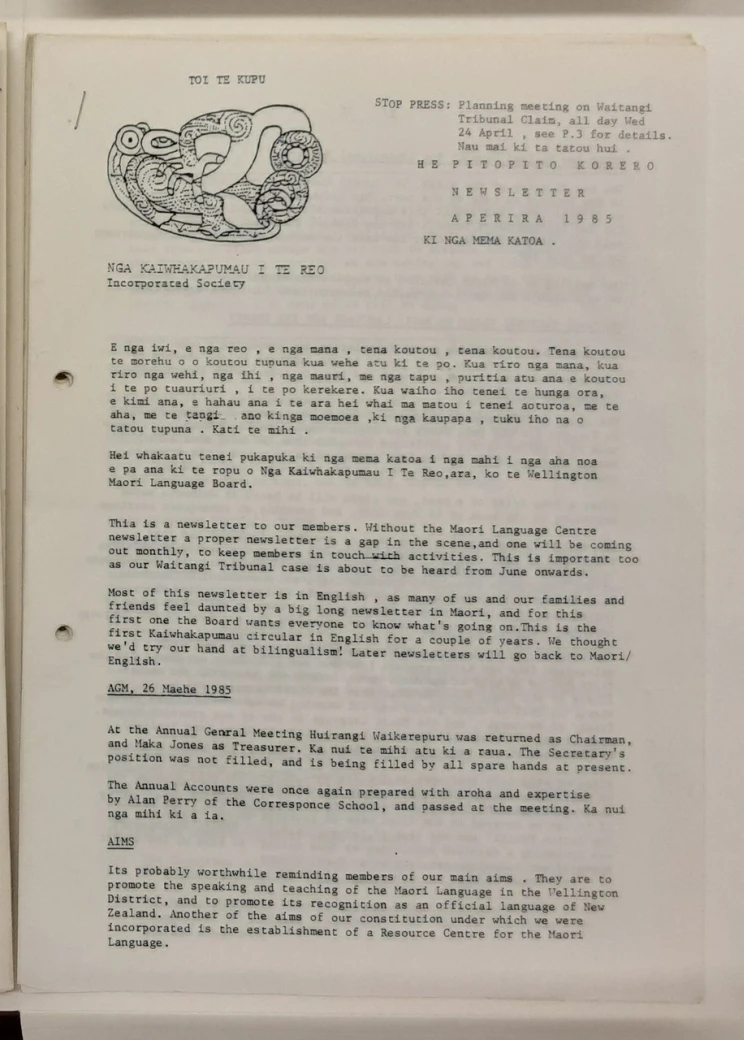

In the years and decades after Te Petihana Reo Māori was presented to Parliament, the fight for active recognition of Te Reo Māori in daily, public life continued. The task of promoting Te Reo Māori was in many ways shouldered by a national network of voluntary community-based Māori Language Boards, among them Ngā Kaiwhakapumau i te Reo, also known as the Wellington Māori Language Board.

The Turnbull Library is lucky enough to hold the Ngā Kaiwhakapūmau i Te Reo collection (ATL-Group-00715). This remarkable collection of approximately 60 boxes, contains the records of Ngā Kaiwhakapumau i te Reo between 1985-1999, including reports, Waitangi Tribunal submissions, hui invitations and agenda.

First page of He Pitopito Kōrero newsletter, Ngā Kaiwhakapumau i te Reo, Aperira 1985. Ngā Kaiwhakapūmau i te Reo Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library. Ref. 91-333, Box 1/2.

Key amongst the successes documented in this collection is the Māori Language claim lodged with the Waitangi Tribunal by Huirangi Waikerepuru, calling for the Crown to recognise te reo Māori as an official language of Aotearoa, and the establishment of Te Reo Irirangi o Te Upoko o te Ika Māori Radio, the first permanent Māori radio station.

Access to this collection requires the permission of Ngā Kaiwhakapūmau i te Reo.

Ngā mihi ki a Piripi Walker mō te tautoko o tēnei pitopito kōrero.

— Rebekah Clements, Assistant Curator Manuscripts

Waitangi Tribunal hearings on Te Reo Māori claim, 1985

The sound recordings of Ngā Kaiwhakapūmau i Te Reo, Wellington Māori Language Board, include recordings of the hearings of the Te Reo Māori claim to the Waitangi Tribunal (WAI 11).

John Rangihau, Ngāi Tūhoe, was one of the eminent kaumātua who spoke at Waiwhetu Marae on 25 June 1985. The submissions of kaumatua covered many aspects of the claim, including the disastrous effects of government policies, the richness of Te Reo and the importance of its survival, and the inextricable relationship between language and culture.

In the introduction to its report the Tribunal said: ‘The evidence and argument has made it clear to us that by the Treaty the Crown did promise to recognise and protect the language and that that promise has not been kept. ’ The wide-ranging recommendations of the Tribunal covered the use of Te Reo, education, broadcasting and public services.

Excerpt 1 from ‘Bruce Biggs and John Rangihau’, 25 June 1985

Speaker John Rangihau. Excerpt 66’00” to 67’10” from ‘Bruce Biggs and John Rangihau’, 25 June 1985, ref. OHT10-0137. Access to this collection requires the permission of Ngā Kaiwhakapūmau i te Reo.

Kua roa tātau e titiro ana i nga kinonga o muri, engari tīmata atu tātou i tēnei rā, ka mutu, kia kotahi ō tātou whakaaro. Ko te tono kē, kia whakaae mai rātou hoki, kia hīkoi tahi tātau, atu i tēnei rā, haere atu. Inā te hīkoi tahi, kia whakaaetia mai ngā āhuatanga e pā ana ki a tāua ki te Māori, kia whakahaerehia e tātou. Kāore au i te tono ki a rātou kia huri katoa mai rātou ki te kōrero Māori, ki te aha. Kāo, engari, kia whakaae mai ō rātou ngākau e tika ana te kaupapa. Kia whakaae mai ō rātou ngākau e tika ana te kaupapa. Mēnā ō rātou ngākau ki te whakaae mai, kua whai rātau, kua whai ratau, kia mohio rātau pēhea tēnei reo. Ki te kore e whakaae mai ō rātou ngākau, ka whakaae noa mai ko ngā hinengaro, e kore e rerekē atu, [Start of 67’00”] engari kia hohoutia e rātou te āhuatanga o te reo nei, o te reo rangatira nei, te reo Māori nei, ki te whakaae mai ō rātou ngākau ki te uru ki reira, kātahi ka taea mai e tātau te hīkoi ki runga atu i ngā kaupapa…

We have forever been looking at the evils of the past, but as we start again today I suggest we need to do it in unity. The request we make however, is that non-Māori agree to come with us on this journey from this day forward into the future. But the nature of this journey together is this, they must agree that all matters relating to us, the Māori people should be managed by Māori ourselves. I am not asking non-Maori to all start speaking Māori or do anything of the sort. No, what I ask is that they agree, deep in the heart that the cause is the right one. That they agree deep in the heart that the cause is right. If they agree in their hearts then they will begin to make the journey of discovery and to find out about this language. If they do not agree deep down in the heart and only agree with their intellect, nothing will change. [Start of 67’00”] but once they accept the nature of this language, this chiefly language, this Māori language, if they agree in their hearts to allow acceptance of it, then we can make walk forward on the tasks ahead…

Excerpt 2 from ‘Bruce Biggs and John Rangihau’, 25 June 1985

Speaker John Rangihau. Excerpt 68’52” to 70’59” from ‘Bruce Biggs and John Rangihau’, 25 June 1985, ref. OHT10-0137. Access to this collection requires the permission of Ngā Kaiwhakapūmau i te Reo.

..hei te mutunga o tana whakapākehā, arā kē noa atu te takoto o tana kōrero, tēnā i aku whakaaro e kōrero nei au. Ināiana ko ēnei whakaaro noa iho. Ka tika ēnei kōrero āna. Kāore he painga o te kōrero mō te whakamāori noa iho i ngā kōrero. Kua roa au e whakamāori ana i ētahi o ngā kōrero a ngā kaumātua nei i roto i te Kōti Whenua Māori, me taku mōhio i a au e whakamāori rā, kāore i te tika te takoto ki roto i ngā taringa o te kaiwhakawā. Kāore i tika te takoto ahakoa i eke i a au ia kupu, ia kupu, engari ko te wairua o te kōrero a taua tangata rā, rerekē noa atu. Rerekē noa atu. Me te aha, me te aha, ki te uru tērā āhuatanga ki roto i te whatumanawa e kōrero ake nei au, hei reira rā anō ka taea e rātou te whakaaro, anei kē te āhuatanga o te Māori me tana whakairo i ana kōrero. Engari mā ō rātou ngākau, kaua mā ō rātou hinengaro.

[Talks initially about having his own statements interpreted] When he had finished interpreting, the statements he made were really quite different from the thoughts I have been expressing. […] The statements he made were correct. There’s no point in talking about this thing called literal translation. I have spent many years translating evidence from our elders in the Maori Land Court but the words I would produce did not give an accurate picture to the judge. I could never get a perfect translation no matter how carefully I focused on each word and phrase, the essence of what that person was saying was actually completely different, completely different. What needs to happen is for the utterances to be perceived by the soul of the listener, the thing I’ve been talking about. It is only then they can say, ‘ Oh, this is the way Maori people feel, and express themselves.‘ But it can only be done through the deeper sense perception of the heart, not through the Intellect.

With thanks to Cellia Joe-Olsen for selection and Piripi Walker for transcription and translation.

— Linda Evans, Curator Oral History and Sound

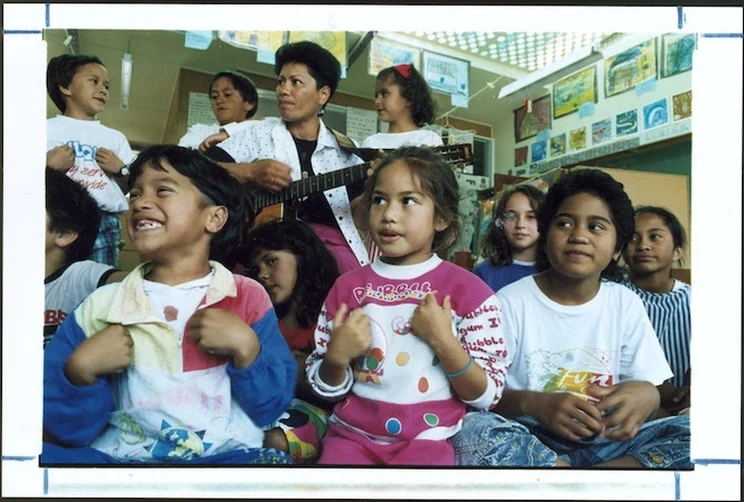

Learning te reo Māori at a young age

While we don’t hold many photographs relating to Te Petihana itself, we do have images that help tell us about what followed, such as the development of kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori.

In 1982 the first kōhanga reo (whanau-based early childhood language centre), Kokiri Pukeatua, was opened in Wainuiomata, Wellington. Since then, 60,000 students have graduated from kōhanga reo.

In the early years, once tamariki left kōhanga reo, there was little follow-up at primary school. This photograph shows Robert Matthews (6), Pera Ulu (5), and Jonda Mahanga (10), with other pupils singing along with Māori language consultant Marion Wharehinga at Thorndon School, Wellington, early 1992.

Students at Thorndon School, Wellington, 29 February 1992, taken by John Nicholson for the Evening Post. Ref: EP-Ethnology-Maori Language-01, Alexander Turnbull Library.

This was the first bilingual class in Wellington. At that time, one-third of Thorndon School’s 100 pupils were Māori and the Education Review Office (ERO) found that its Māori students were performing at the same level as other students. This was attributed to their particular needs being identified and progammes being developed to support or extend their learning.

The recognition of aspects of Māori culture and the regular inclusion of te reo and waiata in class programmes not only helped their test scores, it also boosted their confidence and self-esteem.

In 2011 Pera Ulu recalled loving how the bilingual class allowed her to, ‘continue using te reo to converse with others as well as to develop my English language skills’. Today she is a graduate in Māori studies, a lawyer, and Pouawhina Māori at the University of Auckland, providing support for Māori law students.

The 50th anniversary gives us a chance to reflect on the role of these initiatives in the revitalisation of Te Reo and their influence on Aotearoa New Zealand’s society.

Did you attend a kōhanga reo or kura kaupapa Māori? What was your experience?

— Natalie Marshall, Curator Photographic Archive

Pipi mā: Tae – kāri

Fifty years on from Te Petihana, I’m sharing an item from the ephemera collection that illustrates the contemporary uptake of learning te reo Māori in the 21st century and how gamification can enhance language engagement.

Many people in Aotearoa are learning Te Reo Māori and whether you’re just starting your reo journey, incorporating kupu into your day-to-day vocabulary, or have conversational fluency there are many tools to help you build your knowledge. Gamification incorporates elements of play, competition, and fun to support participation and engagement in language learning. In the digital sphere, gamification is most prevalent in the form of language learning applications however gamification also encompasses analogue learning tools such as card or memory games.

Cards and packaging from Pipi Mā: Tae - Kāri Tae. Jumbo sized memory cards produced in 2018 by Punarau Media Limited.

Pipi Mā: Tae – Kāri Tae was produced in 2018 by Māori owned Rotorua based company Punarau Media Limited (now known as Long White Cloud). Pipi Mā is a jumbo-sized card game that players use to improve their familiarity with and understanding of kupu Māori. The library purchased a copy of the game as the te reo and te Ao Māori focus aligned with our collection priorities. As there are two copies of each card, 24 pairs, they can be used to play snap, or to help the players learn the names of colours, learn flora, fauna and taonga, or to tell stories.

Cards and packaging from Pipi Mā: Tae - Kāri Tae. Jumbo sized memory cards produced in 2018 by Punarau Media Limited.

Te Reo Māori is an integral part of culture and identity and language games like Pipi Mā incorporate many elements of Te Ao Māori, for example cards the cards reference wharenui, poi, arero, kūmara, and kiwi with corresponding ngā tae (colours). With these attractive visual elements including characters and icons the game is targeted towards children, but adults can benefit from playing too. Games like Pipi Mā demonstrate a demand for learning and engagement with te reo Māori and help to support the use of kupu in day-to-day activities and conversations.

— Audrey Stratford, Assistant Curator

Footnote

Letter book. Turnbull, Alexander Horsburgh, 1868-1918: Letter books. Ref: qMS-2050_394_p-309. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Letters of Alexander Horsburgh Turnbull - Volume 1 - 8th January 1891 to 30th July 1894. Ref. qMS-2053. Alexander Turnbull Library.

New Zealand Geographic Board Ngā Pou Taunaha o Aotearoa, Te Rautaki | Strategy 2020-2025: The Memorial Markers of the Landscape, Whakataukī | Proverb.

This is very impressive. Well done to Anthony and all the authors and putters together thereof.