The Story of William Coppell 1844-1913: Part III – The runaway husband and father

The final part of a three-part blog by Helen Smith, Research Librarian, about her family history journey researching the Coppell family. This is a great example of using family stories as well as official documents and newspapers for family research.

The final chapter

In this, the final part of the story of William Coppell, we trace his movements from the mid 1870s to his death in 1913, to see if there is any evidence supporting the family story that he left his wife and children.

We also look at the claims that William and Sarah’s son William had to financially support his sisters and mother when William left the family and that his mother and sisters did not take in his children when they were orphaned.

We use birth, marriage and death registrations, newspapers, postal and business directories, electoral rolls, undertaker’s accounts and government records to find out what William, Sarah and their children were doing, when. Secondary sources provide contextual information regarding William’s life as a gum digger and his final months in the Costley Home.

Read the first two parts of this blog as well as other blogs written about the Coppell family.

William becomes a bailiff in Gisborne

Between Mary’s birth in Auckland in 1873 and the birth of Helen in Gisborne on 4 July 1878, I can find no trace of William or Sarah, apart from William’s name in the Bay of Plenty Times in December 1875, giving support to a candidate in the upcoming parliamentary elections, indicating that he was in Gisborne by this time.

When William registered Helen’s birth he gave his occupation as carpenter. To the confusion of those researching the family in later years, William gave the date of his marriage on this birth registration as 28 November 1869, almost two years after his marriage to Sarah. This serves as a reminder that even official documents can be erroneous.

Photograph of Gisborne taken by William Crawford in 1874. Ref: 1/2-111554-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

In September 1879 the Poverty Bay Herald published detailed accounts of a case before the courts in which E. Ffrancis Ward, jun., solicitor, Charles Flexman, J.P., and four others were charged with riotously taking possession of premises and assaulting William Coppell.

William had been working as a waiter in Gisborne but was now working as a bailiff for Elliott Gruner, a bailiff of the Resident Magistrate’s Court. The job of bailiff could be a dangerous one and William was assaulted in the course of his work more than once.

On this occasion, he had been employed by Elliott Gruner to go alone to Charles Flexman’s house in Waikanae to serve a warrant and writ from the Supreme Court, and take possession of his property. In his statement, William said that he had produced the documents, seized some items kept outdoors and stayed at the property to take an inventory of the remainder.

Charles Flexman enlisted the help of the solicitor E Ffrancis Ward, who arrived on Saturday evening, and the two men tried to lure William out of the house but failed. Mr Ward claimed the goods in virtue of a deed and put Mr Flexman in as bailiff. William said they had no right to do this and stood his ground.

On Sunday morning Charles Flexman gave William a mug of whisky laced with something that burned his throat and he immediately had to lie down. Feeling desperately unwell, he soon had to run to the outhouse. Too sick to leave the outhouse, he could hear the other men nailing up the house to prevent him from re-entering. He did eventually manage to get into town to find people who could help him but Charles Flexman also used that time to gather reinforcements.

When William and his men made an attempt to get through the door a scuffle ensued, William was pushed off the verandah, landing on his back on the ground, and another man was hit with a stick. Finally, outnumbered, William decided they should leave.

Afterwards, Flexman and Ward accused William and his men of having been drunk and abusive. William claimed any bad behaviour on his part was due to being drugged. The judge stated that he thought it was ‘more of an affray than a riot’ but the case went as far as the Supreme Court in Wellington nonetheless. William said at the conclusion of his statement: ‘As far as I am personally concerned I have no interest in the prosecution, but feel rather riled at the affair’.

The Coppell family return to Auckland

The 1880-1881 East Coast Electoral Roll lists William as a waiter in Gisborne and daughter Alice was born in Gisborne in February 1881. The Coppell family moved back to Auckland in about 1882.

In May 1883 William was appointed Assistant Bailiff of the Auckland Resident Magistrates Court, records of which are held at Archives New Zealand. Sarah’s brother, Richard Newdick, acted as surety for William with respect to money passing through his hands in his role as bailiff. The Wise’s New Zealand Post Office Directory records William living in Durham Steet West in its 1883-1884 edition.

Birth notices in Auckland newspapers tell us that Sarah gave birth to a daughter, Rose Phoebe, in March 1884, at Cross Street, while youngest daughter, Violet, was born in October 1885 at Cobden Street, Newton.

New Zealand Herald, 19 March 1884:

Coppell.—On March 5. at Cross-street, Newton, the wife of Mr. Wm. Coppell of a daughter.Auckland Star, 7 November 1885:

CAPPELL.-On October 25, Mrs Wm. Cappell, of Cobden street, Newton, of a daughter.

Photo of Rose Coppell (1884-1933), taken ca 1888.

The Wise's New Zealand Post Office Directory, the first national postal directory of householders, usually lists the head of the household and, sometimes, their occupation. The information was sent in by postmasters for each area and sometimes the entries were out of date, so it is not surprising to see William still appearing to live in Cross Street in the 1885-1886 edition, then at Cobden Street in 1887-1888. The New Zealand Electoral Rolls, however, list William as a bailiff, living in Edwin Street in June 1884 and August 1887.

Photo of Auckland Magistrates Court. William was attached to the Magistrates Court as a bailiff. Re: 1/2-125532-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

We know for certain that William was still employed as a bailiff in 1889, and had been for the previous six years, because the Auckland Star stated so when, on 18 September of that year, it reported that William and a fellow bailiff, John Brierly, had been assaulted by members of the Good family in Upper Queen Street.

The City of Auckland Electoral Roll of September 1890 again lists William as a bailiff but tells us his address was now Pratt St. The Cleaves Auckland Directory of 1890 and 1891 also has William in Pratt Street but gives his occupation as turner. Wises of 1892-1893 gives his address as Ireland Street, Ponsonby.

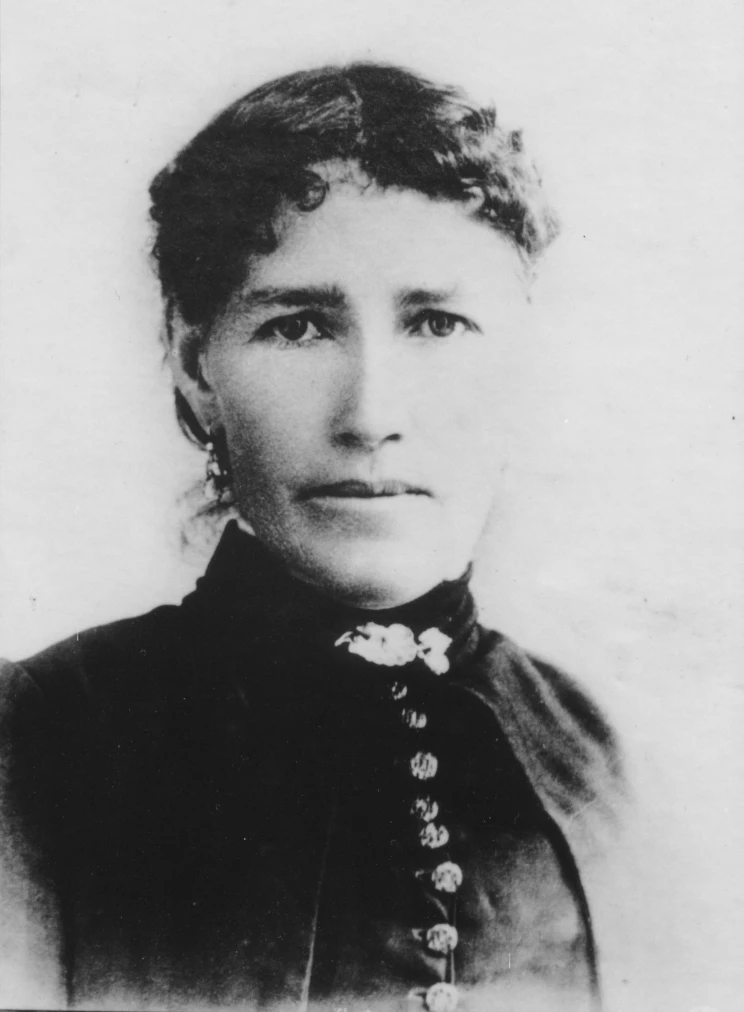

Photo of Sarah Coppell nee Newdick, ca 1880s.

Gum digging at Ru Point, Kaipara

While it is possible that William was living apart from Sarah in Auckland in the late 1880s, it is the appearance of his name on the 1893 Northland Electoral Roll, as a gum digger at Ru Point, that sees him making a distinct move away from the family. Ru Point sits on the eastern side of the Poutu Peninsula, in the Kaipara Harbour.

Kaipara had been a bustling timber port since the 1860s, exporting thousands of tonnes of kauri timber and gum. Ngāti Whātua used the Kaipara gum fields as a source of income and came to rely more heavily upon it as their lands were sold. The school master at Poutu School wrote in 1893 that gum was fetching high prices and many Māori children were absent from school because they were working in the gum fields with their whānau.

As well as Māori, the gum diggers were European immigrants, notably those from Dalmatia, on the Adriatic coast of Croatia, and people, like William, who had been ground down by the long depression of the 1880s and 1890s.

Gum digger with gum digging equipment, ca 1910. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-009781-G. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Very little financial investment was required and, unlike gold-digging, finding gum and getting paid for it was guaranteed, even if the earning capacity was not great. The gum diggers’ small huts were made from whatever materials could be acquired nearby, whether that be earth, nikau and raupo, or wooden planks and iron.

William is likely to have used knowledge from his goldmining days, as well as his carpentry skills, to set up his home away from home. He may have lived and worked in a group, as the European gum diggers tended to, or preferred to be independent of others as most British or New Zealand-born gum diggers did.

Son William, who had turned 21, and become eligible to vote, in February 1893, appears on the City of Auckland Electoral Rolls in his Uncle John’s house in Beresford Steet from 1893 to 1896.

It has taken some investigation to untangle the various electoral roll entries for the two Williams, complicated by the fact that the Wise’s Directory does not agree with the electoral rolls.

The family grows

William had returned to Auckland from Ru Point, at least temporarily, by March 1894, when he appears on the third supplementary City of Auckland Electoral Roll, together with Sarah, and daughter Amy, in Collingwood Street. He gave his occupation as cabinet maker and Amy appears as a tailoress.

This is the first time Sarah and Amy enrolled to vote, women having won the right to the vote the previous year. The Wises’ Directory tells us that their house was three doors down on the left side from Ponsonby Road.

Photograph of Amy Coppell.

In May 1894, Amy gave birth to a daughter, registered as Ethel May Copal, but known as May McGinley. Amy married Thomas McGinley, who was probably May’s father, the following year. No father is named on May’s birth registration. After the birth of her second child in early 1896, Amy applied for financial relief for her parents from the Charitable Aid Board, records of which are held at Archives New Zealand.

Amy stated on the application that William was a bailiff but that he was destitute and unable to support his family. Of the family of seven, only daughters Mary (17) and Helen (16) were earning an income, bringing home five shillings each, while the rent on their house in Cobden Street was six shillings, sixpence a week.

It was noted that son William, who had married the previous year to Margaret Annie Chappell, was working at Warnocks, tanners and leather merchants. The youngest two girls, Violet and Rose, were students at Beresford Street School.

Looking south over Freemans Bay...1880s. Panoramic view looking south over Freemans Bay showing Ponsonby, Franklin Road, (centre), College Street (left to right), Scotland Street (right), Howe Street, (centre background), Pitt Street Methodist Church (left background), Mount Eden (left distance) and Beresford Street School. Heritage and Auckland Council Archives. Image on DigitalNZ.

The question of the second family

The story that William had a second family has only been passed down through one of Violet’s daughters, who believed that William left because Sarah did not want more children after Violet’s birth in 1885. She also said that William reused some of the names of Sarah’s children when naming his second family. I have found no birth registrations for children with the surname Coppell that are unaccounted for but not finding evidence does not make this an impossibility. The births of children in remote areas were sometimes not registered and it was not a requirement to register the births of Māori children until 1913. In addition, any children William fathered outside his marriage may not have had the surname Coppell.

Photograph of Helen Coppell.

Gumdigging at Waimauku

Although the 1896 application to the Charitable Aid Board states that William was a bailiff, electoral rolls had not shown this as his occupation since 1890. The 1896 Cleaves Auckland Directory has William as a cabinet maker in Wellington Street. Meanwhile, the Waitemata Electoral Roll, published on 31 October 1896, lists William as a gum digger at Waimauku.

Photograph by Josiah Martin, showing James Fletcher weighing gum in front of a gum digger’s raupo hut, probably at Waimauku, ca 1897. PH-1958-1-15464. Auckland Museum.

Proof that the gum digger in Ru Point and Waimauku was my ancestor William, came when I looked further at the Charitable Aid Board records. In 1897 William’s brother, John, who had been an engineer on various coastal vessels, including the Government paddle steamer Luna and the steam ships Tauranga, Star of the South and Wellington, became too unwell to work. When, in November 1897, William applied to the Auckland Hospital and Charitable Aid Board for money to help his brother John, his wife Susan and stepson, on grounds of sickness and destitution, his occupation was given as ‘late bailiff, Auckland, now gum digger’. John died of cancer of the throat and tongue, aged 60, in June 1898.

William does not feature in the Wises’ Directory of 1896-1897 but reappears again in the 1898-1900 editions in Cobden Street, perhaps by virtue of his being the ‘head’ of this family, although he was not living there continuously. It is possible that he lived in the family home at times, perhaps in the winter months. In June 1897 William was ‘fined 10s, in default 48 hours' imprisonment’ for drunkenness in Auckland. According to the New Zealand Herald it was the second time he had been charged with this offence.

The New Zealand Electoral Rolls tell us that William was working as a labourer in Te Kuiti in 1899, quite a distance from his family. In the same year Sarah is listed on the Auckland City Roll in Cobden Street. Her occupation is given as ‘home duties’. This is the second, and last, time she features in the electoral rolls. The Cleaves Directory, which does not list William from 1897 to 1904, has an entry for Sarah at Cobden Street in 1900. When the family moved to Mackelvie Street in Grey Lynn, in about 1901, it was William’s name published in the Wise’s Directory and Cleaves Directory each year until 1908. The Electoral Rolls tell a different story: that William had returned to Waimauku and was working as a gum digger from 1902 to 1911.

Five unidentified gum diggers with spear and spade in their hands standing in front of a raupo hut. Probably taken at Waimauku by Josiah Martin, ca 1897. PH-1958-1-15467. Auckland Museum.

William turned 67 in 1911 and gum digging was hard physical work. William would have worked all day to dig up the nuggets of gum, lugged them in his pikau to his hut or tent, and spent his evenings scraping them clean with a jack-knife by candlelight. Gum diggers were generally not well regarded by society; however, there were educated, intelligent people amongst them who chose not to accept charity when they came upon hard times, including publisher and author A H Reed, who would later write books about his and his father’s time on the gum fields.

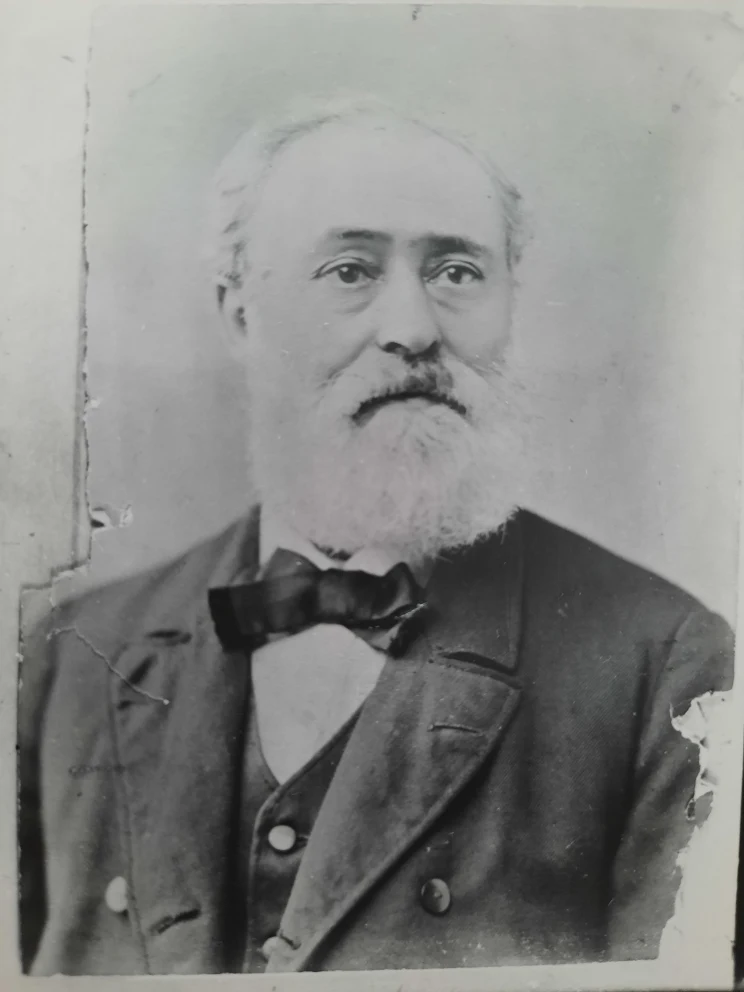

A photograph identified in the 1980s by my grandfather, Luther Hare, as an ancestor of his. This image comes from a glass plate negative which had been made from an original photograph prior to the 1930s. Luther was uncertain of the man’s name but believed he was an engineer on the Rotomahana. Having eliminated each ancestor by dating the clothing and age of the man, and excluding those I already have photographs of, the possibility remains that this could be William Coppell in the 1900s, wearing an old suit from the 1870s. I have not located any other photograph of him.

Three marriages

Helen married in December 1903 to Arnold Hare. We know that she continued to work as a tailoress after her marriage as her eldest son, Luther, later recalled sitting beneath his mother’s sewing machine while she worked. The Hares were a refined and religious family, and Helen may not have wanted ‘gum digger’ to appear on her marriage certificate, preferring instead to state that her father was a pattern maker. A pattern maker made wood patterns for the construction of metal objects, something that William, as a turner, could have done.

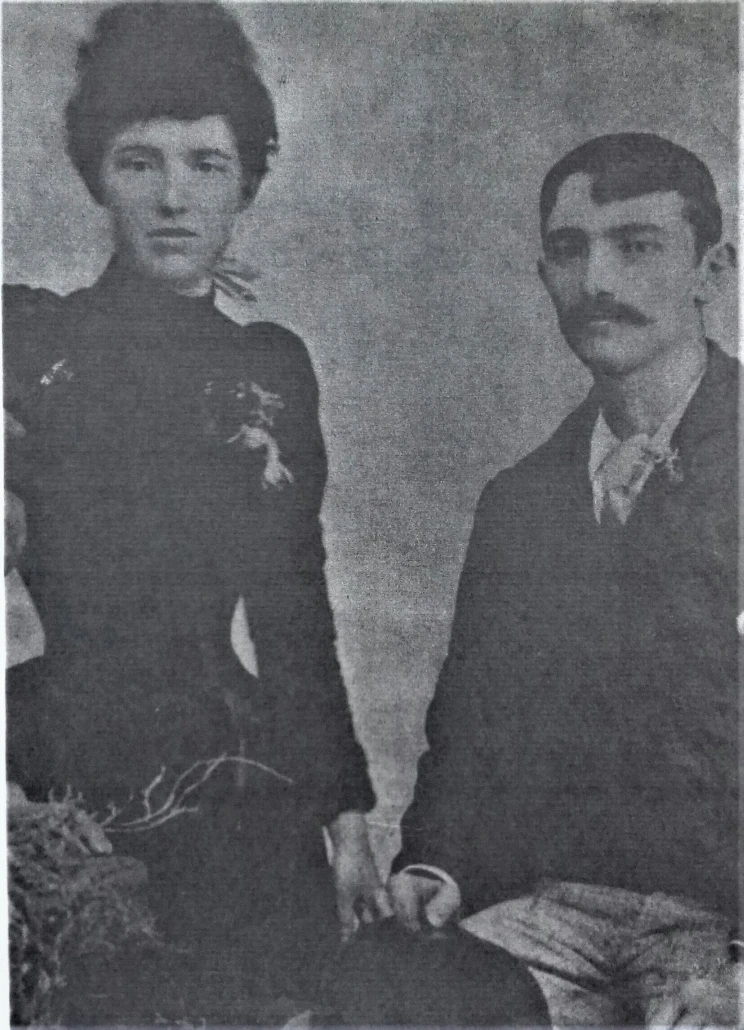

Wedding photo of Helen and Arnold Hare, 1903.

Alice, Violet and Rose continued to live at the house in Mackelvie Street with their mother until 1908, earning money as seamstresses. I have been unable to prove through midwife registrations (which only began in 1905), or business directories, another story passed down, that Sarah was a midwife who never lost a mother or baby, but she may well have supplemented her income in this way.

Photograph of Helen Coppell. My mother remembers her grandmother as very gentle, sweet and reserved.

My mother remembers her grandmother as very gentle, sweet and reserved.

When Violet married Richard Buckby in February 1908 the notice in the Auckland Star stated that the wedding took place ‘at the residence of the bride’s parents, MacKelvie-street, Grey Lynn’ and, as tradition dictated, the names of the fathers of both parties are published and not their mothers.

Alice also married in 1908, to William Webster, but she left him a month later. When they divorced in 1915, the New Zealand Herald chose the headline ‘The wife who ran away’. The Auckland Star reported that Alice was ‘variable in her moods’ and on their honeymoon she had told her new husband that ‘she did not love him and it would be wicked to live with a man she did not love’.

Photograph of Alice Coppell.

Sarah’s death

On 3 October 1908, Sarah died of a cerebral haemorrhage at the Buckby’s house in John St, Auckland, aged 59 years. Sarah was buried near her father at Purewa Cemetery. The undertaker’s record is, perhaps, a more accurate statement of how things stood in the family than Violet’s marriage notice.

Mr Buckby paid for the funeral and her son William’s address and occupation are recorded. Her husband William is not mentioned. However, Sarah’s death notice says she was the ‘dearly beloved wife of William Coppell’ and a bereavement card in the Auckland Star reads ‘MR W. COPPELL AND FAMILY wish to tender their heartfelt thanks to all kind friends for their sympathy in their late sad bereavement; also for all telegrams, letters, and floral emblems.’

When Sarah and William’s son, William, lost his wife the following year, he published the following in the New Zealand Herald in memory of both Sarah and Annie:

COPPELL— loving memory of my dear mother who departed this life on October 3, 1908, also my dearly-beloved wife, who departed this life on August 4, 1909. Through all pain at times she'd smile, a smile of heavenly birth. And when the angels called them home, she smiled farewell to earth. Heaven retaineth now our treasure, earth the lonely casket keeps, And the sunbeams love to linger where two loving hearts do sleep. Inserted by her loving son and her husband (William Coppell)

William Jr published the same memorial to his mother again in October 1910 and Mary, Rose and Violet also published memorial notices for their mother in 1909 and 1910.

William Coppell Jnr’s death

Tragically, young William himself died on 18 October 1911, two weeks after a clay pit accident at his workplace, aged 39. The coroner’s report, published in the Auckland Star on 20 October, states that ‘a portion of clay, weighing from 80lb to 100lb fell on his back as he was bending to the shovel’. Having suffered ‘a fracture and dislocation of the lower part of the spine […] it was decided that his only chance was an operation to relieve the pressure on the spinal cord. The patient died about three and a half hours after the operation, from shock as the result of injuries received followed by the operation in his very weak state.’

Photo of William Coppell (1872-1911) and his wife Margaret Annie Coppell nee Chappell (1870-1909).

When William Jr died, the Public Trustee found that he had 5s in savings, furniture worth £2 6s 8d in wages, and jewellery valued at 3s 6d – these assets amounting to less than a gum digger might hope to earn in a week. School admission registers show that his children, Philip (11), Alfred (6) and Raymond (4) left Avondale School to enter Remuera Orphan Home on 1 December 1911.

The eldest, 14 year old William, had already left school to earn a living, which was usual at that time. It is true that the boys were not taken in by their Coppell relatives but their personal circumstances prevented them from doing so.

My blog about the Hare family details the poverty and nomadic lifestyle Helen endured in these years. Amy McGinley too, lived with her husband’s family in a cramped and difficult environment, a situation that I am told continued for several years, as is evidenced by an Auckland Star article of 5 December 1907.

The Coppell sisters remembered their mother and brother in the Auckland Star in October 1912:

COPPELL.—In loving memory of our darling mother, Sarah Coppell, who departed this life on October 3rd, 1908; also, our dear brother, William Coppell, who died October 18th, 1911. And with the morn those angel faces smile, Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile. Inserted by her loving daughters.

William enters the Costley Home

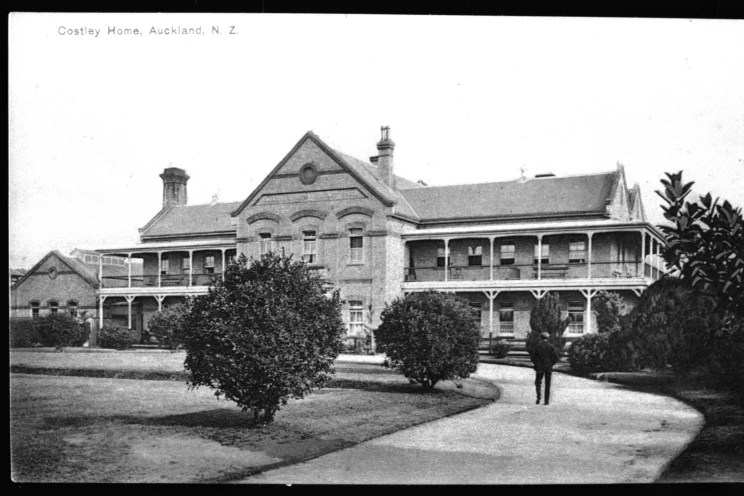

By February 1912, William, suffering from cancer of the tongue and pharynx, had become too unwell to dig for gum any longer and he entered the Costley Home in Epsom.

The Costley Home was run by the Hospital and Charitable Aid Board with the intention of providing accommodation and care for poor men and women. About two thirds of the inmates were over 65. Many of the men had done hard physical work in remote locations, such as goldmining and gum digging, and had not married or had children.

Postcard of the Costley Home, later part of Auckland Hospital. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 229-1. Kura Heritage Collections Online.

The main building had beds for about 50 women and included maternity wards. There was a separate men’s block housing about 130 men in six dormitories but William may have had a bed in the small cancer ward.

The Home included men’s and women’s dining rooms, heated reading and sitting rooms, a small library and a chapel. George Pearson, grandson of Alice Pearson (who had died in 1894), recalled his father taking him and his sister to sing to William in the home.

William’s death

William died at the Costley Home on 6 Jan 1913, aged 68. The funeral director’s records tell us that William’s funeral was paid for by his daughter, Alice Webster, and he was buried with his wife Sarah at Purewa Cemetery.

Four carriages had been hired for Sarah and William Jnr’s funerals but only one carriage was requested for this funeral. William’s daughters did not have his name inscribed on the headstone and no memorial notices appeared in the coming years.

A death notice, published in the New Zealand Herald on 8 January 1913 suggests that William may have remained dear to Sarah to the end: ‘On January 6. William, beloved husband of the late Sarah Coppell, aged 69. The funeral will leave from Little's, Marble Arch, at 3.30 pm to-day (Wednesday), for Purewa’, although it was not her who wrote these words. Her actions, her thoughts and her feelings about William remain unknown.

I had Sarah’s picture sitting on my desk while I researched the Coppell family and, at times, I asked her to tell me what really happened. She remained silent, of course. I did look for information about Sarah and this blog was meant to tell her story as well as William’s but, like most women of the time, she has left little record of herself. She has no voice. Sometimes evidence is found in the lack of information to be found — the truth is in the silence.

Photo of the author at the grave of Sarah and William Coppell, Purewa Cemetery, in 1996. The inscription reads ‘Oh for the touch of a vanished hand and the sound of a voice that is still!!’

Vitai Lampada! — pass your knowledge on to future generations

Alice Pearson’s grandson, George Pearson, having written down what he could remember of the early days, finished what he likened to a ‘chain letter’ to his descendants with:

There you are now, someone, it’s up to you. Vitai Lampada! Keep the ball rolling and this will swell into a volume of names and facts that will grow with New Zealand’s history. It may be all you have to leave behind you, but please God, the day will come and the volume will become more precious to its recipient than all the world’s gold.

He refers to a poem penned by Henry Newbolt in 1892 which sees the sporting ideals of fairness, courage and duty transplanted from the English school cricket field to the battlefield. It ends:

This they all with a joyful mind

Bear through life like a torch in flame,

And falling fling to the host behind —

‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’

Even when the rules of the ‘game’ are unfair and the reality of life is brutal, the light of joy and hope survives, to be passed on to those who come after us. There you are now, someone, it’s up to you. Keep the ball rolling. Write down the stories you have heard in your own family, do some research to find the lost, and incorrectly boxed, pieces to complete the picture, Ask a Librarian if you need advice, and pass the stories on.

Thank you

Thanks to my mother, Margaret Smith, for passing her research notes, and her passion for history, on to me. Thanks also to those who contributed over the years, including Marie Corser, Merle Loveday, Daphne Coppell, Isabel Mathieson, Eileen Wootton, Rose Mathieson, Donald Buckby, Sherryle Lane, Sandra Parker, Michael Robinson, Rosamund Bradshaw, Vicki Slattery, Fiona Gordon, Robert Knights, Susan Brodrick, Peter Hare, Maureen Murphy, Red Coppell, Eric Secker and William G. Coppell.

Read the first two parts of this blog as well as other blogs written about the Coppell family.

Selected sources

General

Wises’ New Zealand Post Office Directory on Ancestry Library Edition and microfiche

New Zealand Electoral Rolls on Ancestry Library Edition and microfiche

Kia ora cousin!

Those Williams make life difficult, don't they?

My grandfather was Alfred Newdick - *this* William's grandson.

I've also written a bit about the family - particularly on William (jnr)'s oldest sons' WWI service.

http://themadnessofhamsters.blogspot.com/2015/04/war-and-escape.html

Thanks Anne. Lovely to hear from a descendant of William Coppell Jnr and to see someone else writing about their family stories. I will reply privately also.