Flying Nun in the studio

In the second of two blogs about preserving the Flying Nun Records master tapes donated to the Library in 2018, we take a closer look at the work Senior AV Conservator Nick Guy is doing to digitise and preserve the audio held on the tapes.

Happy 40th Flying Nun!

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the founding of New Zealand’s iconic indie record label Flying Nun Records. Last week on the National Library blog, we heard from Imaging Services about their work on the Flying Nun Project, photographing the label’s master tapes donated to the Library in 2018.

In our second Flying Nun Records 40th anniversary blog, we interview Senior AV Conservator Nick Guy, who has been leading the Library’s work to preserve the content held on these precious tapes.

Nick Guy, Senior AV Conservator at the Alexander Turnbull Library, digitising audio from the Flying Nun Records master tapes.

Michael Brown: Your role with the Flying Nun Project is to digitise the master tapes and other AV recordings. Why do we digitise AV recordings?

Nick Guy: We digitise AV recordings to preserve their accessibility for the future.

For most of the last half of the 20th century, the creation, storage and exchange of AV content was dominated by magnetic tape recorders and magnetic tape media. A few decades on, those magnetic media are beginning to degrade, their components decaying in ways that make them difficult to use.

Now that creation and exchange of AV content is overwhelmingly digital, magnetic tape players are obsolete and new machines and spare parts are no longer manufactured. When the existing machines can no longer function, the content stored on magnetic AV media will become inaccessible.

Faced with these twin factors of decaying tapes and technological obsolescence of the playback equipment, the only choice is to migrate the content to new formats that can be better maintained. Right now that means digitisation to high-quality AV file formats that can be safely stored on digital mass storage systems, and cared for within digital preservation programmes.

Is there an overall philosophy or approach you take to AV digitisation?

Some people think my job must be to make the old recordings sound “better”. That couldn’t be further from the truth. All the sonic characteristics of the original recording, even those perceived as imperfections, are a part of the historical document and should be preserved.

My job, then, is to safely playback the original recordings to sound exactly as they were intended and capture a high quality lossless digital recording of that output. This creates a digital preservation copy, that is (as much as possible) exactly like the original, that can serve as a surrogate when the original media is no longer accessible.

Once a digital preservation copy is created and stored in the digital archive, enhancement can be done, case by case, on new copies. In the case of the Flying Nun Collection, copies are being provided to artists and mastering engineers so they can revisit and technically enhance their work for a modern listening environment. This can be done again after again if that digital preservation copy of the original tape is kept safe.

Close inspection of magnetic tape during an initial slow spooling helps ensure the tape is in a safe condition for further spooling and playback.

What formats have been digitised thus far?

Since 2019 the cassettes, videotapes, and most of the DATs have been done. Right now I am focused on digitising the 1/4" open reel master tapes. Roughly half of those are done.

Getting old tape recordings to a playable state can be complicated. What processes and treatments do you use to stabilise AV media? And can you tell us about a particularly tricky problem you’ve had to solve?

A thorough inspection of the tape is always the first step when starting work. What kind of tape is it, what condition is it in? I want to make sure that nothing is going to happen to it if I put it on a tape machine.

A common mode of degradation in tapes of this era is known as Sticky Shed Syndrome (SSS). The magnetic layer of a tape should be hard and glassy but in tapes with SSS, the complex chemistry of that layer has changed, and the surface of the tape becomes soft and tacky.

Playing an untreated SSS tape is not an option. At best, tape will stick to the tape playback head, gradually shedding material from the magnetic layer until the build-up clogs the playback head, causing loss of fidelity in the digitisation. At worst, the layers of the tape will adhere together and tear the magnetic surface right off the backing tape, causing permanent damage to the audio it contains.

Sticky Shed Syndrome can often be discovered by letting the first meter of the tape unwind itself into the box. A tape with advanced SSS will quickly stop unwinding and cling to the reel. That’s a tape that is not safe to play or even spool.

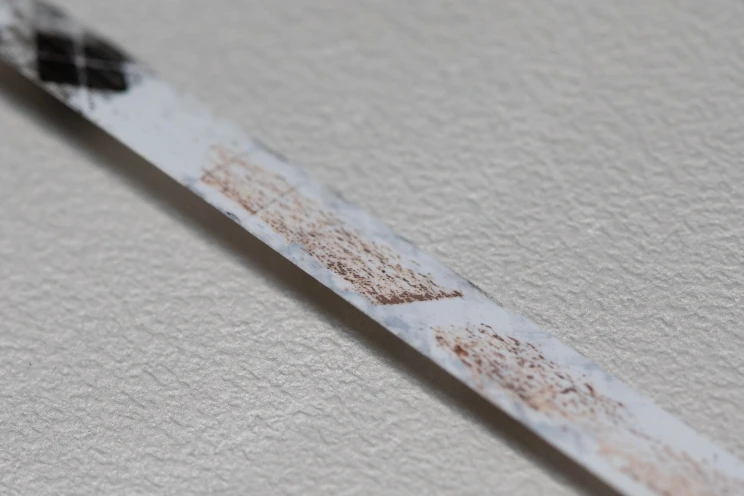

Tape exhibiting sticky shed syndrome (SSS), through adhering to adjacent tape. The magnetic layer of a tape should be hard and glassy but in tapes with SSS, the complex chemistry of that layer has changed, and the surface of the tape becomes soft and tacky.

Treating SSS involves carefully incubating the tape for several hours in an environmental chamber at a stable temperature around 50⁰ C and 0% Relative Humidity. Commonly referred to as 'baking', this treatment was even patented by tape manufacturer Ampex after they identified the problem with their tapes, and has been used for decades. Baking temporarily cures the sticky shed symptoms and you have about a fortnight to copy the tape. After that symptoms begin to return.

What I am seeing is that incubation times are increasing. When I started this job almost 20 years ago, 8 hours was sufficient. Now I am finding it takes 24 to 48 hours to get the same effect, and for some tapes much longer. This observation is being reported by AV conservators around the world and suggests that tape condition is worsening with time.

Around 60% of the 1/4" tapes in this collection are suffering SSS and we bake dozens each month.

Treating sticky shed syndrome involves carefully incubating the tape for several hours in an environmental chamber at a stable temperature around 50⁰ C and 0% Relative Humidity, a practice commonly referred to as 'baking'. Photo: Nick Guy

There’s an obligatory 'please don’t try this at home!' message here, at least not without doing some research. It is impossible to attain those low, stable baking temperatures in a domestic oven — and some types of tapes should never be baked.

Another complexity with the Flying Nun Collection is the prevalence of plastic leader tape sections in the tapes. Leader is a coloured plastic tape that contains no audio but is used at the start and end of a tape, and sometimes spliced into separate different songs or sections of a tape. These plastics have their own degradation characteristics and may be less stable than the audiotape. Sometimes leader tape sticks tightly to a neighbouring section of audiotape threatening to tear the magnetic layer away.

In some cases, I have ended up separating leader and audiotape, millimetre by millimetre, over several hours.

Sometimes leader tape sticks tightly to a neighbouring section of audiotape threatening to tear away the magnetic layer. Here, tiny sections of the magnetic layer have stuck to the leader tape.

There are various brands of tapes in the Flying Nun Collection, which have been stored in different places and conditions over the years. The main donation made in 2018 had been held in Auckland for many years, while subsequent donations came from all over the country. Have you noticed patterns in the condition of the tapes?

A while back I thought I had identified a regional trend but now I’m not so sure. Making predictions about tape behaviour is an occupational detective story with plenty of dead ends.

Firstly, there is the diversity of tape stock in this collection. Ampex 456, Maxell, AGFA PEM and Scotch are the dominant brands and these are pretty typical for New Zealand at that time. But as Flying Nun went global, so did the tape stock in the archive. Some of the recordings were made in Europe, the United States. There is even some ORWO 106 tape that seems to come from Russia.

Then, within a single tape type, there are variations in formulation and batch quality across the years. Recently I discovered that the codes present on Ampex 456 tapes (the most common stock in the Flying Nun Collection) relate to the date they were packed, not the batch of tape they came from, so not much help there either.

Combine that with differences in local storage conditions of each tape there are always multiple variables to consider and plenty of caveats to any prediction.

Another issue with recordings on legacy formats is sourcing and maintaining old playback equipment. What machines are you using and how do you keep them going?

For the 1/4" 2-track masters I am mostly using Studer A810s. They are nice machines to use and are really gentle with tape.

Keeping them running is a challenge. Our technician regularly services the tape machines to ensure they are operating correctly. This is crucial if the goal is to make accurate preservation copies. He has found all sorts of ways to keep the machines running as they should, including repairing circuit boards and replacing chips. It's a vital skill set for this work.

Generally, there are no new parts available, so if something needs replacing it is a case of getting one from our limited stocks or a sacrificial broken-down machine, or trying to track down a part from eBay or another source. I’m always looking for something.

Get in touch if you have some gear we could use!

Tape spooling on a Studer A810 tape recorder in preparation for playback and digitisation.

Recordings on open-reel tape can be made with a range of settings, including the recording speed and pre-emphasis EQ. What has the quality of technical information for the tapes been like and how do you ensure you’re playing tapes back correctly?

As with most things about this collection, there is a lot of variation in the technical documentation. Many tapes come with detailed technical information and include alignment tones for optimising playback. Typically, these tapes were sent somewhere to be mass-produced on vinyl, cassette, or CD.

Some tape boxes identify the tape recorder used but say nothing about the settings used. So I often have to search for a manual for that machine to see what the range of possibilities could be.

Other tapes come with no technical documentation whatsoever. Often these are mix masters, for example, submasters or rough mixes that probably weren’t intended for use beyond the studio, or perhaps were home-studio recordings where engineering details weren’t the main focus.

Tape playback speed is generally easy to figure out with popular music and master tapes, though occasionally there are notes that tapes should be played back a set percentage faster or slower. This would give a more energetic or heavier sound to the recording.

Pre-emphasis and de-emphasis frequency equalisation is a noise reduction technique built into tape recorders. By applying pre-emphasis to particular frequencies when recording and applying a complementary de-emphasis during playback, the intended sound is reproduced with a reduction in tape hiss.

However, there are several standards for this equalisation, and the correct de-emphasis setting must be applied to avoid changing the sonic character of the recording. If the technical documentation doesn’t identify the standard used, typically NAB or IEC, it can be tricky to choose.

On some recordings, it is obvious, on others subtle. You need to do a few tests, look around for clues, and pick the one that sounds 'correct'. Similarly, if a tape doesn’t have alignment tones you have to make some assumptions about what level the tape was intended to be played at. In both cases, it is important to keep technical documentation about the decisions and interpretations that are made.

Tell us about Dolby. What is Dolby? How is it applied to tape recordings? And what are some of the challenges it has presented with the Flying Nun tapes?

Dolby noise reduction is a widely used technology developed to reduce the low-level noise or hiss inherent in magnetic tape recording. It is a more complex implementation of the pre-emphasis and de-emphasis concept.

In the Flying Nun Collection there are 1/4" tapes recorded with both Dolby A and Dolby SR systems.

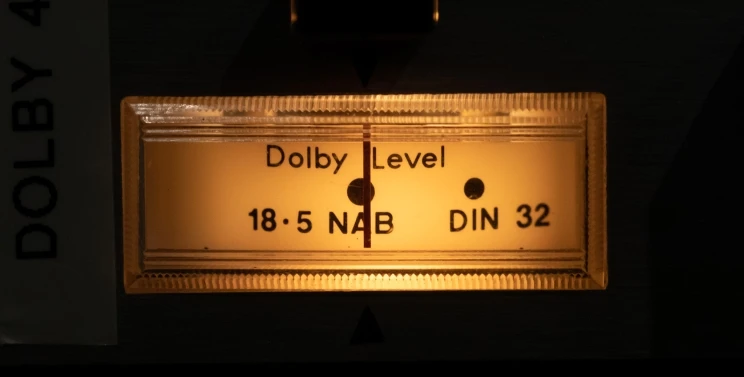

Dolby decoding units. Recordings made using Dolby noise reduction must be played back through the Dolby processor to decode the signal. When done correctly, the output will be the original sound with reduced tape hiss.

When making a recording, the original sound is run through a Dolby analogue audio processor on its way to the tape. This Dolby encoding boosts certain sonic characteristics of the signal. When the recording is played back it must be run through the Dolby processor to decode the signal. If done correctly, the output will be the original sound with reduced tape hiss.

The challenge, then, is to correctly decode the Dolby processing. This is critical because such complex audio processing relies upon the audio input level into the decoders. If the recording is decoded with the wrong input level, the results will be quite different to what was recorded.

In theory, that level is indicated by alignment tones, added to the tape along with the audio recording, ideally with some guidance in the technical documentation. With calibrated Dolby decoders and the appropriate Dolby alignment tones, we can obtain excellent results.

But sometimes alignment tones are not present on the tape. Tape edits may have dissociated sections of tape from their tones. Perhaps some recording studios operated at a self-evident 'standard' calibration that, decades later, is no longer self-evident.

Sometimes the tones are there but the results just sound 'wrong' to me, in that I struggle to believe the sound was what was intended by the creators of the recording. Was this recording made with inaccurate or faulty equipment? Were the artists/engineers following a technique that I don’t know about, or deliberately doing something non-standard because they liked the effect?

Close up of a Dolby 361 meter during Dolby level alignment in preparation for playback and digitisation. The dot indicates the correct input level for decoding.

I feel that deciding if the decode sounds right introduces a little too much subjectivity in the context of preservation digitisation, especially when Dolby decoding cannot be reversed.

My strategy, therefore, is to create two digital versions at the same time. The first is a 'best efforts' Dolby decode with original hardware processors. The second is a non-decoded version that is, by definition, 'wrong', but that could be used in future as source material to attempt a better decode, with different hardware or perhaps software decoders that may become available.

Playing back a tape is one thing, Dolby decoding another. What other equipment is involved in the digitisation chain and what does it do?

The signal chain is actually very simple, comprised of only the essential components. The output of the Studer tape machine goes directly into a Digital Audio Denmark AX24 analogue-to-digital converter and the digital output of that is recorded to a 24-bit 96kHz broadcast wave (BWF) audio file. That’s it.

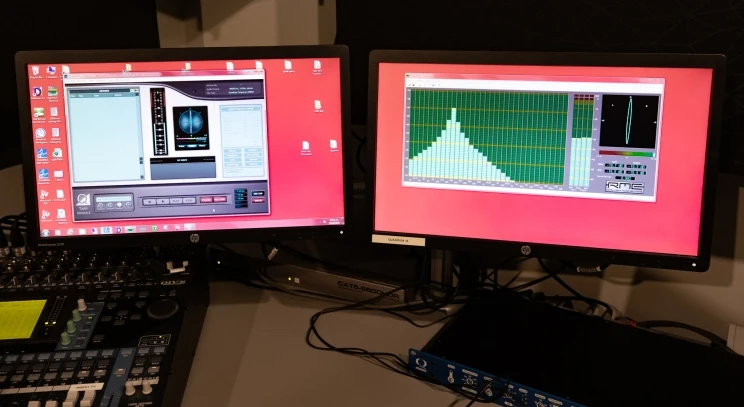

The recording computer runs some analysis software, a spectrum analyser and phase scope. For Dolby tapes, a distribution amplifier and the Dolby 361 units are added into the chain.

Quadriga digital capture workstation.

What’s it been like to work on a collection encompassing so many iconic New Zealand recordings?

I am enjoying working with this collection on many levels.

Technically, the collection is very diverse, virtually a survey of music production techniques across two and half decades. There are many formats and interesting variations within those. As I have alluded to, there is the overall challenge in AV preservation to accurately reproduce detailed recordings when the technical context of their creation can be largely gone. So, I’m always researching or figuring out some detail or other. Piecing together some of the technical elements has lead me to some enjoyable diversions learning the history of several New Zealand recording studios.

It is also great to work on recordings where the sonic details are artistically intentional. These are audio artworks and there is a genuine pleasure in hearing these recordings of the original tapes. There is a sense of responsibility to understand and preserve all that detail. I often think about the artists and engineers who made these recordings while I am working, all the hours that went into getting these tapes to sound the way they do.

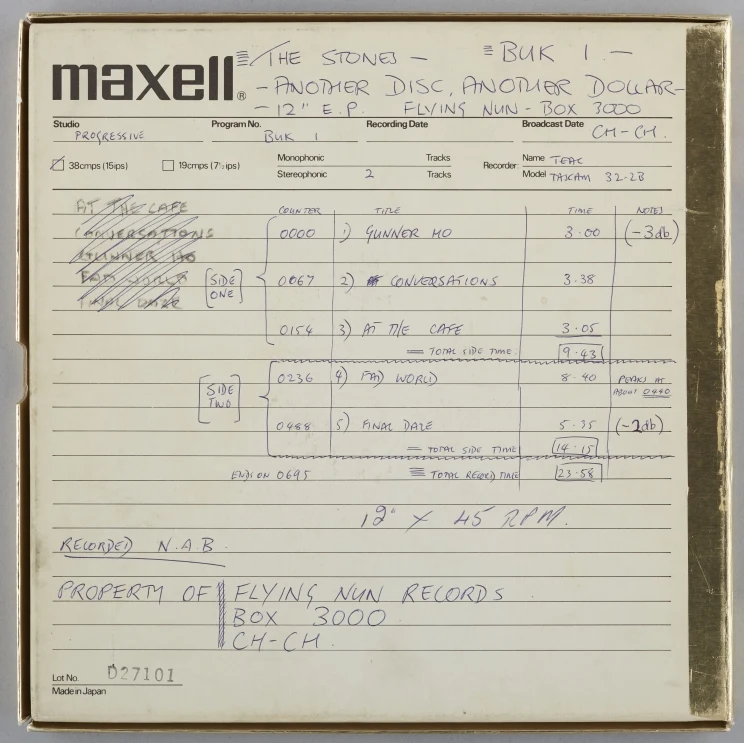

What part of the sound they were focused on, the distortions and happy accidents. On the tape boxes I read warm, funny, or perhaps slightly distrustful communications to anonymous engineers further along the production chain who stand between the artist and the audience, and who have the power to corrupt the work by applying their own vision of what a record 'should' sound like, to make it 'better'. I remember writing the same kind of thing myself in the past and laugh: in a sense, I am now that anonymous engineer between the artist and the future audience.

Tape box for The Stones / "Another Disc, Another Dollar" E.P. Masters (ref: FLYT10-335).

The professional ethics and experience of a Conservator come into play here. One should be aware of the technical, historical and cultural aspects of recordings, how recorded sound has changed over time and how perceptions of what sounds “good” also change. By being aware of these factors, one can make informed choices in the present and for the future.

Naturally, I take pleasure being a part of the project to ensure the preservation of this body of work, knowing a high-quality copy of these degrading tapes is being created in a preservation focused archive. And it is satisfying to be supplying copies back to Flying Nun and the artists themselves for remastering and reissue, to see some of those barriers to access removed and to think of people enjoying this music again from the original source. There really are cool details in these new transfers that I have never heard in previous releases and I can’t wait to hear some of the remastered releases.

And, of course, it is more than a little bit fun to work with the master tapes from some of my favourite acts. I think ‘Sing Song’ by the 3Ds was the first Flying Nun song I ever heard, so it was a thrill to take that tape out of its box and hear it from the master tape.

What are some of your favourite interesting discoveries heard so far?

There are so many. Most recently I've worked on some early Tall Dwarfs live recordings that were great, with so much energy, attitude and raw creativity. There are some unreleased Gordons recordings that were exciting to hear and the b-side to the first Nelsh Bailter Space single is pretty special. The Stones’ "Another Disc Another Dollar" is a new favourite of mine.

I’ve also really enjoyed some of the early Flying Nun releases recorded at Nightshift Studios in Christchurch. I had never heard of many of these groups some of which are quite far from what is generally understood to be the Flying Nun sound.

There is still some way to go with digitising the whole collection, which has grown since the first donation in 2018. What’s up next for AV digitisation?

Later this year, I’ll begin digitising the multi-track master tapes. Multi-track formats in the collection range from audiocassette 4-track all the way up to 2” 24-track. So, there has been a lot of work going on, sourcing and restoring playback machines for all these formats.

No doubt we’ll talk more about that in due course.

Nick Guy in the AV preservation studio.

Access the Flying Nun collection

To listen to the digitised tapes in the Flying Nun Collection, you will need to visit the National Library in Wellington and use the workstations in the Katherine Mansfield Reading Room.

Three series in the Collection contain digitised material. Browse items in these series via the links below:

In the Open reel audiotapes series, 145 items are currently available to access. Another 100 items will be added by the end of May 2021.

Post-digitisation processing is currently underway for the 244 DAT tapes, which should become available for research access in the coming months.

Except where indicated, all photographs featured in this blog were taken by Mark Beatty.