Ep.7 Christmas in the collections 2021

The 2021 Christmas in the collections includes a Samoan Christmas card, Christmas ephemera including a memorial card/pass to a Christmas hui at Rātana Pa and Bruce Mason's ‘The End of the Golden Weather’.

Christmas traditions

Library Loudhailer host Seán McMahon talks to library staff Ulu Afaese, Pacific Virtual Museum Content Analyst, Audrey Waugh, Assistant Curator and Paul Diamond, Curator Māori about items from the collections and their Christmas traditions.

Transcript

Speakers

Seán McMahon, Ulu Afaese, Audrey Waugh, Paul Diamond.

Seán McMahon: Kia ora e te whānau and welcome to the Christmas edition of the Library Loudhailer, the monthly podcast of the National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa. We’re coming to you live from the Lilburn Room, so this not the usual studio, so if you hear sirens in the background this is just a bit of atmospheric noise. So, I hope you've all had a wonderful and productive year despite all the Covid challenges we've all faced.

My name is Seán McMahon and together with my special quests we will be presenting some festive Christmas items from the Collection. Today in the studio we have Ulu Afaese, Content Analyst with the Pacific Virtual Museum. We also have Audrey Waugh, Assistant Curator in the Contemporary Voices and Archives team.

Audrey Waugh: Kia ora.

Seán McMahon: And Paul Diamond, Māori Curator with the Alexander Turnbull Library.

Paul Diamond: Kia ora.

Seán McMahon: So, we might start with Ulu. Ulu can you take us on a journey into a Christmas in Samoa?

Ulu Afaese: (Laughs) Malo soifua. I’m laughing because I actually missed my cue. Malo everyone! Yeah to be honest, Christmas in Samoa, I’ve only done Christmas in Samoa once and that was the lead up to my wedding. But before that last time I was in Samoa was in 1995. But no it was awfully nice, but yeah I guess it’s like a Kiwi Christmas: nice beach.

Paul Diamond: A bit hot.

Ulu Afaese: Yeah. Way hot!

Seán McMahon: I bet.

Ulu Afaese: Yeah! So the items that I chose were, um, there were two items and I’ll just go through the first one. The first one is titled: “An Ephemera Folder of Octavo Size Relating to Samoa, 1970 to 1979” and they consist of pamphlets of tourist destinations so Aggie Grey’s, for example. Also promoting to, yeah, come to the islands during Christmas, which unfortunately, you know, we can’t.

Seán McMahon: Aggie Grey’s is quite a famous spot, isn’t it? In Apia, right?

Ulu Afaese: Yeah! It’s a famous spot. Heard so many things about it and going to Samoa, went in there, and yeah it’s really nice. I don’t know the current state of it because, I’m assuming because of the lack of tourists, it’s probably not as thriving as it usually is, but hopefully post-pandemic it can go back to its former glory.

So some of these items were donated by the Department of Anthropology from Victoria University of Wellington in 2001. Others were donated by Claire Murphy in 2014 and Rachel Brown in 2001. I mean aside from the pamphlets and it will take listeners back because we had an airline called Polynesian Airlines, and yeah it has a timetable so it will be interesting for those who want to check it out.

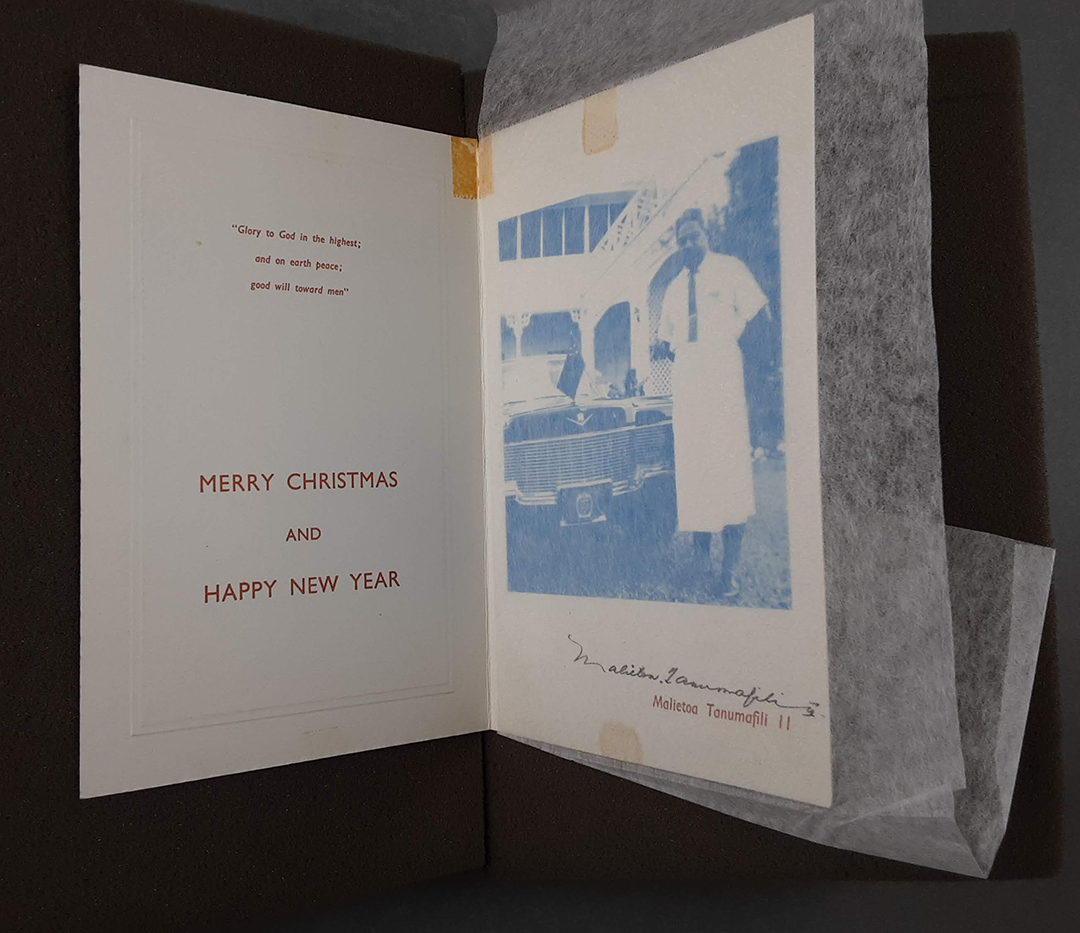

But the item that stood out for me was a Christmas card and the title is “Vailima. Fa’avae I Le Atua Samoa. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year” and dated 1970. In the front it has . . it’s a normal Christmas card. Inside it has the message on the left and on the right is a picture of the Head of State, Malietoa Tanumafili II, so he was Head of State post-independence and he’s standing next to a car and it has his signature on the bottom right hand corner. I think, um, yeah I guess I would compare that to receiving a Christmas card from the Queen and I feel like that item has historic significance.

Seán McMahon: So that’s a real big deal?

Ulu Afaese: Yeah for me it’s a big deal. I encourage anyone who’s in Wellington to, or who is thinking of coming to Wellington, I think we might have a link to the item right? You know they can request it and have a look for themselves. It’s an important Christmas card.

Going to the second one. This one stood out to me because it just had a lot of good memories about Christmas and celebrating an Island Christmas in Auckland, actually.

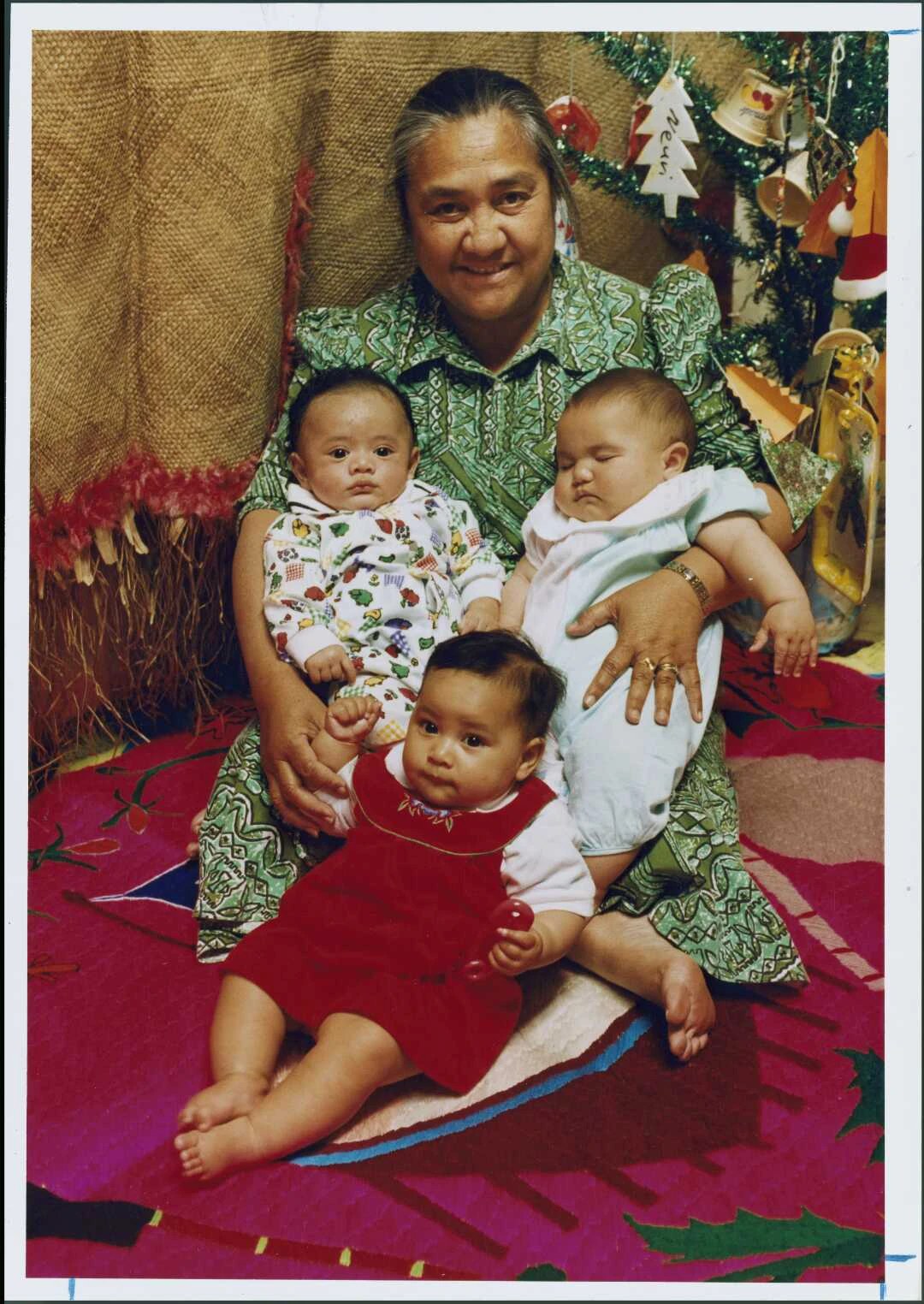

It’s titled ‘Fereni Ete with babies who appeared in her Christmas play’ and the photograph is taken by Ray Pigney and this is in 1995. It’s talks about how the play fuses Christmas and Samoan culture and how it shows the baby Jesus being born in Samoa.

So I guess for me it’s just significant because it’s no secret that Islanders go all out for Christmas. Yeah I think for church, Christmas plays are quite a big deal, Christmas songs. I think I mentioned how this is the second most stressful day behind White Sunday, I mean the amount of work goes into plays and getting the songs right, so yeah, some very good memroies. But also food as well. Church, food, are basically the main ingredients in an Island Christmas.

Seán McMahon: Ticks all the boxes.

Ulu Afaese: Yeah yeah.

Seán McMahon: So we’re saying before, do you notice much difference between a Christmas in the islands, in Samoa and one here in Aotearoa?

Ulu Afaese: They’re relatively the same. It’s just, I mean, you know it’s not, I would say for most Islanders, it’s not really a ‘secular’ holiday, if you know what I mean? The focus is on the religious aspect and then with Pacific culture comes in the coming together and sharing a meal and, yeah, so those are the two main components of a Pacific Christmas, which I love and enjoy.

So yeah it’s a really big deal. I just remember my aunty, she always does her house up in Massey, in West Auckland. She always does her house up with the lights and everything, yeah it’s quite a spectacle. So yeah, we go all out and it’s such an enjoyable time.

Seán McMahon: Is your aunty competing with the neighbours like some streets where every house has a go and puts lights up?

Ulu Afaese: Funnily enough the neighbours are starting to compete with her? I think shes done it since the early 2000s, and they took a break from it a couple of years back and now they’ve resumed doing it again. And there’s always this whole tradition of different churches, youth groups, coming to my Aunty’s place and singing carols, Samoan carols. I honestly forgot the Samoan name for it, but yeah that’s always a big deal. Just busloads of church groups coming to her house and singing. So yeah it’s really cool. I miss that.

Seán McMahon: Yeah I would love to hear it myself, I’m sure it’s spectacular...

Ulu Afaese: I’m not that good of a singer (laughs)

Seán McMahon: And I heard a rumour, something about Jim Reeves, and your family? Is that true? Listening to Jim Reeves?

Ulu Afaese: Oh yeah, yes no, that’s always the album. My father-in-law has done that now. He’s carried that on and plays the Jim Reeves Christmas Album. It’s either that or Elvis. The oldies would always play those kind of Christmas songs. There’s no Mariah Carey, no they don’t play that. It’s either Jim Reeves or nothing.

Seán McMahon: Yeah my father used to listen to Tom T. Hall on a Sunday after church. So, country western, maybe there’s a link there between that and the Catholic Church, I’m not sure.

Ulu Afaese: But yeah, I just wanna give a shoutout to my family in Auckland because this will be the third Christmas I haven’t spent with them. I mean, apparently it’s not really that safe in Auckland at the moment, but I just hope that they’re safe in Auckland spending their Christmas time. So yeah, I miss them heaps.

Seán McMahon: Well that’s great. Thank you, Ulu. That was lovely to hear about a Samoan Christmas.

So now we might transfer over to me, and I’ll have a more traditional New Zealand Christmas, really.

I’m going to read an extract from The End of the Golden Weather, which is a play by Bruce Mason. The play is about a boy’s loss of innocence in the Depression era in New Zealand in the 1930s. It was written for solo performance, it was turned into an award-winning film by Ian Mune in 1991. The original play was workshopped in 1959, performed in 1960, published ‘62 and then again in 1970, and it was later performed in the Edinburgh Festival.

Bruce Mason had preformed this play around New Zealand over a thousand times, so he’d covered all the major cities plus all the small towns throughout New Zealand. The section I’m reading from is from a chapter in the play called Christmas at Te Parenga, and Te Parenga is a fictitious beach which is basically Takapuna where Mason grew up. And so, he’s set it in this fictious beachfront township on Auckland’s North Shore. As I said it’s in the 1930s, and the boy who is the main character is nameless throughout the play, but he’s about 12 they say, is the memory that Mason’s going back to, to his childhood. Right:

“Christmas Eve: A day as long as a year of penance. In the kitchen, my mother’s face is flushed from the stove from which, all day, she has drawn forth cakes, scones, biscuits, mince pies; they stand on the bench outside, cooling in the shade, platoons of them, four abreast, marching into the barracks of abundance. My brother and I hide behind the door until our mother leaves the room; creep in like conspirators making the secret sign of the order, fingers crooked: scoop them into bowls of icing, chocolate, lemon, vanilla and feel the cool, sharp flavours sting our tounges. Caught once, smacked, sent outside; caught twice, smacked harder, sent to the beach.

My father comes home early, springing without the weight of the year. A fortnight to go before he shoulders the next load of days. He changes into shorts, fills a glass wit beer, bubbles with talk. As my mother passes him, weary, abstracted, he sweeps her on his knee, nuzzles in her neck. She screams and smacks him: the kitchen is full of laughter.

On the mantlepiece, a hundred cards shout greetings in a hundred scripts. Santa Claus, radish-cheeked, ice-blue eyed, his face a mask of merriment, guides his sleigh through flaking snow or pauses by a chimney, weighed down by magic freight. `Greetings, greetings, greetings. How’s the wife, how’s the kids, what’s the news of Uncle Jim?’ The world’s voice rich, thick and loud, raised in a mighty chorus of solicitude.

And I, pious and smug, my mind swilled clean with the foaming suds of goodwill, take my brother off to Church for Christmas Eve. The long nave sucks us down towards the altar, dim and ruddy-glowing; all round, devout dark heads bob on a trough of gloom, like corks on a mysterious sea.

Mr Thirle at the pulpit, a huge benign penguin...

`Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a Son…’

The Star, the Wise Men, While Shepherds Watched, Away in a Manger, the Child: the immemorial images softly fall, slowly sinking through the mind like distant jewels. A great bronze eagle on the pulpit, wings spread for flight, glares at the Book, daring it to be true...

Christmas morning. The dead pillowcases alive, miraculously quickened in the night: the Word made bulging Flesh. Tearing of paper, shouting: turning keys in clockwork inwards, stifling chagrins that the watch isn’t real, that the doll doesn’t speak—warning noises from the bedroom: `Don’t disturb; your mother’s tired’ – creeping in to see if it’s true; weary, bleary parents, faces tight with tiredness and the effort of goodwill at five in the morning. Laughter cracking and spouting Love... love.

By ten o’clock on Christmas morning, the sun wraps Te Parenga round like a hot oilskin, searing the back under shirts, stinging bare arms and legs. A clear green sea edges up the beach in finicky slaps like a coy woman, marking its progress in half-hoops of delicate froth. We rush to immerse ourselves in the glittering element shouting ‘Merry Christmas!’ to our parents, to our friends, watching their faces narrowly for signs of grace. Will Mr Johnson’s hard old dial, as blank as prison wall, fissure and crack with the earthquake of a smile? No, it won’t. But at least he mutters through closed, thin lips: `Merry Christmas, lad.’ Oh, and look at crabby old Miss Mackay, who never ventures further in than ankle depth, never allows herself more pleasure than a cold dour sluice of her mottled, flesh-rippling shoulders, or a hand-scoop of sea to slosh into her cavernous armpits—look at her now, moving slowly and majestically out to sea, powered by an antique breaststroke, a noble and dignified old whale. And out we come, dripping and gleaming, our souls unsullied white in the glorious no-past, no-future: only the immaculate present, endlessly pouring its essence on us.

The day moves on, so white and generous that nothing must sully it. `What! Tears on Christmas Day! What! Quarrelling on Christmas Day!” as though on any other day these sins were venial but today, mortal. Every irritant, however slight, is mercilessly held up to show its hideous blackness on the white sheet of Christmas. Peace on Earth! For twenty-four hours. Fatigue shall be banished, discomfort shall not be admitted. Smiles will be fixed on Christmas Day and worn like honourable decorations until the clock striking twelve, proclaims release.

Seán McMahon: So that’s an extract from The End of the Golden Weather and we’ve touched on Auckland today already. Stephen Lovatt who is a well-known New Zealand actor performs extracts from this work every Christmas Day at Takapuna Beach. He’s been doing it for the last fifteen or sixteen years, so if you’re fortunate enough to be in Auckland this Christmas it would be well worth going down to the beach and seeing Steve’s rendition of the play. Currently he’s actually touring the play around the country, but that’s actually been put on hold because of COVID, so he’ll have plenty of time to practice it.

But Ulu, that’s interesting there that’s like the 1930s, but the church is very dominant there in that piece, and the food is also very dominant, so you know there’s a lot of passing of time and cultures, but there’s a lot of things that hold us together.

Ulu Afaese: Yeah true. That’s right.

Seán McMahon: Now Audrey, I think you’ve got something special for us over there in the Ephemera section?

Audrey Waugh: Yeah, I certainly do, with Ulu and Sean your depictions come back to what Christmas is all about and today I’ve decided to look at some of the commercialisation and advertising that surrounds Christmas, it’s inescapable!

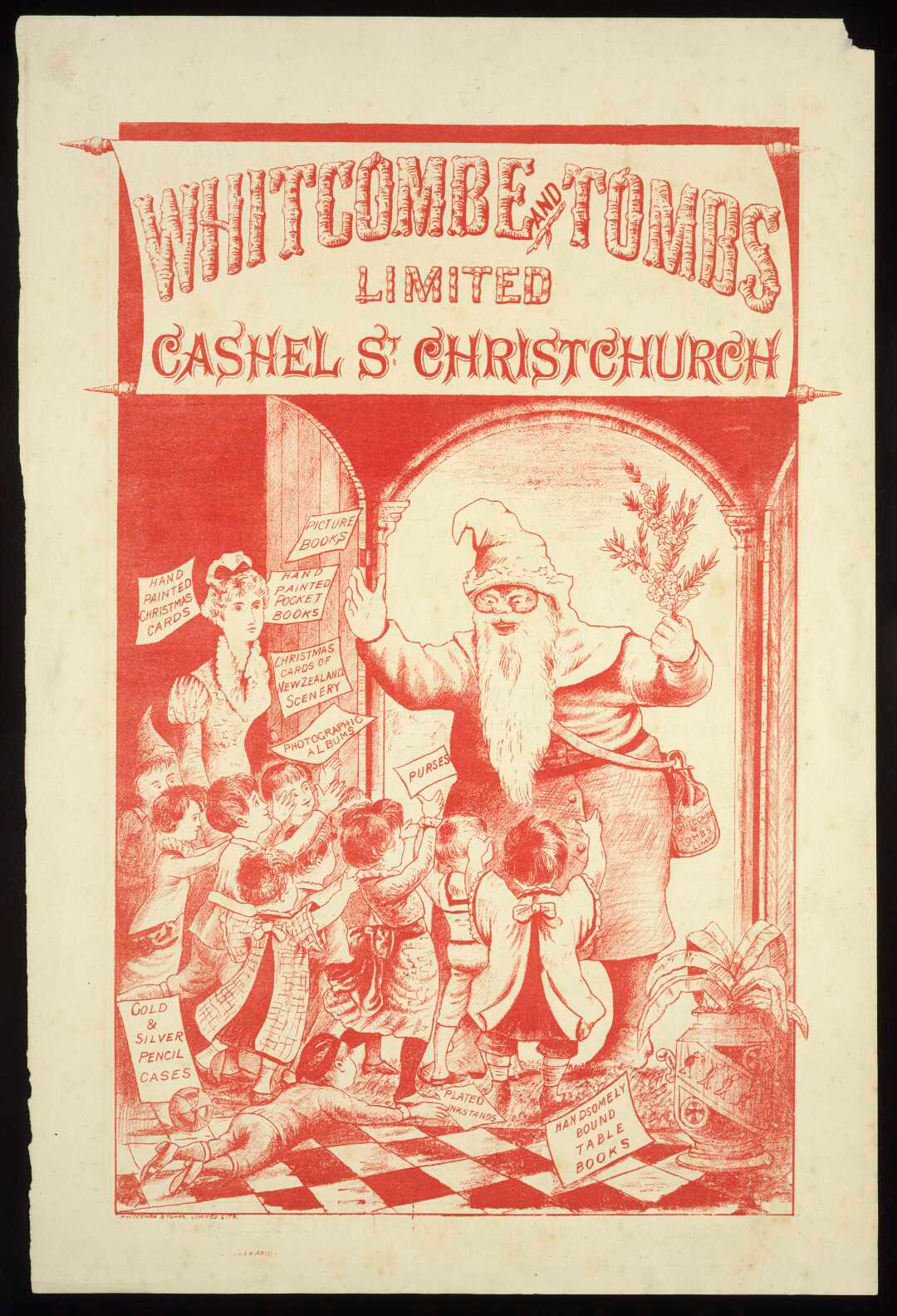

I’ve selected a festive lithograph in red on white paper from the library’s ephemera collection and this was produced by Whitcombe and Tombs, in Cashel Street, Christchurch.

For those of you who don’t know, a lithograph is a form of printing using plates (which can be made of stone or metal) to create multiple copies of an illustration, and this was particularly convenient for advertising and promotion.

The library purchased this item from Anah Dunsheath in 2002 to build up our ephemera collections relating to retail, significant New Zealand companies, like Whitcombe and Tombs, and as early examples of lithographs.

This illustration shows Father Christmas with a long white beard, wearing a classic Santa hat and a Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd satchel, he’s walking through the doorway and carrying a sprig of mistletoe in his hand. Father Christmas is being greeted by a crowd of excited children who are almost falling over themselves to get to the presents and to meet the big man himself, and there is even one little boy who has actually fallen on the floor in his excitement.

Inset labels floating around the children show that consumers can purchase the following sought after goods: handpainted Christmas cards, picture books, pocket books, Christmas cards of New Zealand scenery which were particularly appealing, photographic albums, purses, gold and silver pencil cases, plated inkstands, and handsomely bound table books.

These advertisements were distributed to Christmas shoppers promoting a range of products made by local Whitcombe and Tombs. The company was established in 1882 and had stores around New Zealand. The company would later merge with Coulls, Somerville & Wilkie to form the familiar Whitcoulls Ltd. I imagine some of our listeners are doing their Christmas shopping with Whitcoulls this month. I know as a librarian I both receive and buy books to give out to my friends and family.

Compared with the modern Christmas traditions we see now in New Zealand of a summer beach Christmas, Santa in jandals and the BBQ on, maybe even a beer in hand, in this depiction we see a Eurocentric Christmas and Father Christmas in this advertising. And this shows the influence of the time, the Northern Hemisphere and traditions of England were clearly an impact on early New Zealand advertising.

It was run in 1886 so you can imagine that many families who migrated to NZ would be experiencing their first summer Christmas, leaving behind the cold, snowy, feasting Christmases of home. I don’t know about you guys but I think I’d certainly prefer a summer Christmas out on the beach.

Seán McMahon: Yes I would certainly agree with that and uh the trick in Wellington is trying to find somewhere to go the beach [laughter]. Yeah so ah, I used to shop there when I was a kid, at Whitcombe and Tombs on Lambton Quay, so it’s now where Glassons and Hallensteins are. So that was the original building in Wellington and I think it's very, very true that it’s the types of items on offer there are very different today where everyone wants a Nintendo or they want something high tech, back then it was sort of a practical pen and papers, books, you know, colouring things, and so forth.

Audrey Waugh: Yeah absolutely and as a printer and book publisher they made their start with compulsory primary schooling in 1887, so then they really cornered the education market but now they really expanded to anything and everything your heart desires, it sounds like we're promoting Whitcoulls.

Seán McMahon: Yeah yeah we are promoting Whitcoulls! It’s a phenomena though how religious texts, how much they were sought after back then, you know and a publishing company could be founded around the publication of religious texts. That’s just a…. now it’s romantic novels and things you know so, it’s very, it’s a bit of a move there.

Audrey Waugh: I’s a bit of a shift and I imagine getting a bible or being handed down the family bible was quite a significant Christmas present.

Seán McMahon: Absolutely yeah you’re talking sort of uh, family heirloom type there with a nice bible that you know comes down and ends up going to the Turnbull Library. I mean I’m not just saying that, we do have a few bibles in the library yeah.

So Paul, welcome, kia ora, and uh looking forward to your piece here.

Paul Diamond: Well, I’ve sort of taken inspiration from Audrey and found something in ephemera.

Audrey Waugh: Oh fantastic!

Paul Diamond: But it’s kind of related to what kind of has been keeping, one of the project that’s been keeping me busy in 2021. The project to digitise this collection of books that the Turnbull library catalogued a few years ago called Books in Māori so that’s a bibliography, it’s just a list of, not just books actually, everything they could lay their hands on in 2004 that had been printed in Maori; newspapers, magazines, posters, flyers, everything. But it only went up to 1900 and gradually, we’re beginning the project to digitise that and make it available on Papers Past.

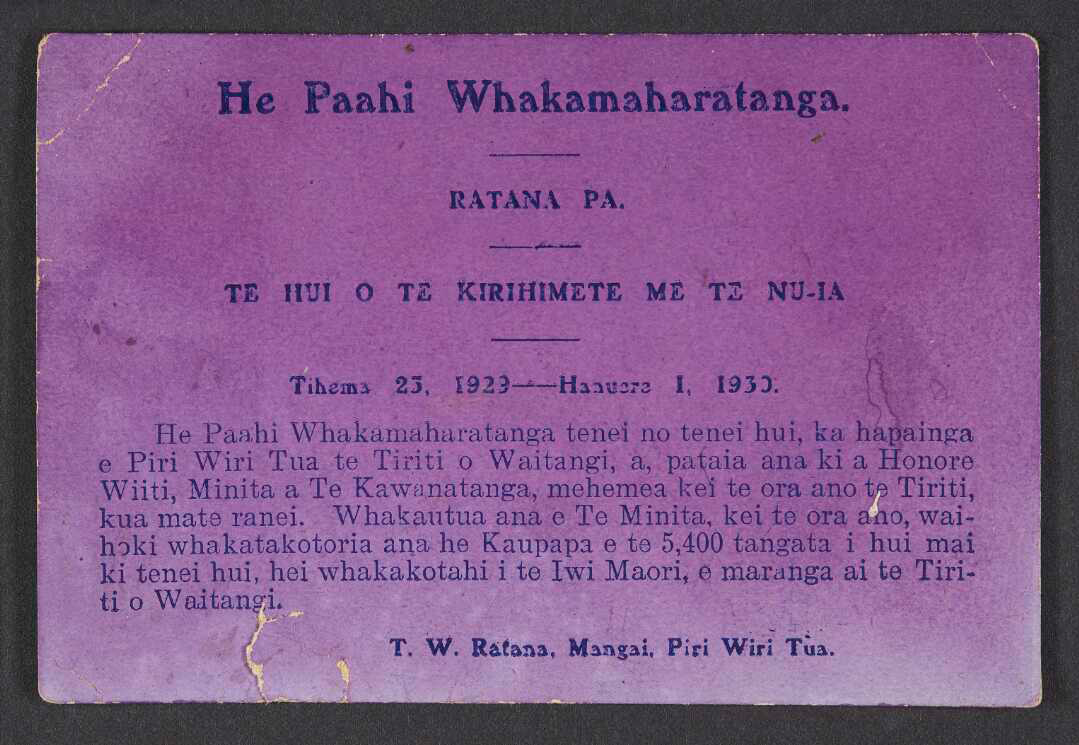

But when I, when the annual call came out for Christmas material, I put in Kirihimete into the catalogue and found a pass that was actually bought, I remember this being purchased by Audrey’s predecessor Barbara Lyon in 2013 it was bought at auction and it’s a little pass, little card and it’s digitised so we’ll have the link on the website so you can actually see and have a look at this for yourselves and it’s sort of a pinky purple colour and it says ‘He Paahi Whakamaharatanga. Rātana Pa. Te Hui o te Kirihimete me te Nu-Ia. Tihema 23 1929 - Hanuere 1 1930’ so it went from 1929-1930.

This was the Christmas hui that they had at Rātana Pa so this is the settlement just south of Whanganui on the West Coast of the North Island where Rātana Tahupotiki Wiremu Rātana founded the movement and faith, the Rātana church. So people might know that in January there are the commemorations of Rātana’s birth on the 25 January 1873 and the politicians go up, but that’s just one of the days, there’s a whole lot of other days, for Rātana followers, adherents, but the one that gets all the attention is when the politicians go but interestingly in 1929 and 1930 it was on December the 25th and I saw a reference saying that Rātana’s birthday was on Christmas Day but apparently that’s not thought to be right now but anyway that year they had the hui then and that’s what this little card is commemorating. And there’s just two sentences on this card it says:

He Paahi Whakamaharatanga tenei no tenei hui, ka hapainga e Piri Wiri Tua te Tiriti o Waitangi, a, pataia ana ki a Honore Wiiti, Minita a Te Kawanatanga, mehemea kei te ora ano te Tiriti, kua mate ranei.

So that first sentence is saying ‘this is a little memorial card/pass for this hui, that was organised by Piri Wiri Tua te Tiriti o Waitangi’ um and these were names that Rātana gave himself so, Piri Wiri Tua was the campaigner, and it’s interesting actually that he adopted um I think this is right te Tiriti o Waitangi as a title, ‘ask the minister of the crown’ and I was a little bit puzzled about this ‘Wiiti’ but I did a bit of research on Papers Past and Veitch was the MP for Whanganui.

Seán McMahon: Ah right.

Paul Diamond: And he represented the government at this hui so this is how things were translated because there aren‘t as many letter in the Māori alphabet so things got transliterated. So it was, the question was asked by Rātana you know,‘does the treaty live, or not?’‘kei te ora ano te Tiriti, kua mate ranei?’ And the last sentence is:

"Whakautua ana e Te Minita, kei te ora ano, waihoki whakatakotoria ana he Kaupapa e te 5,400 tangata i hui mai ki tenei hui, hei whakakotahi i te Iwi Maori, e maranga ai te Tiriti o Waitangi."

So the minister answered ‘yes it does live indeed’ and furthermore um there was this kaupapa laid down by the 5,400 people who went to that hui um to unify the Māori people and that last part ‘e maranga ai te Tiriti o Waitangi’ to uplift or give life to I guess um the Treaty of Waitangi. So I thought that was interesting so you’ve got um there were apparently 24,000 people followed the Rātana church in 1930 and when the population was only 67,000 that was 36% of Māori were members. It still significant apparently the latest figures show that it's more than 40,000 people and there‘s also several thousand people in Australia.

Seán McMahon: Ok.

Paul Diamond: So it’s still the biggest Māori religious faith and uh just to finish I was able to find a little bit of context in wonderful Papers Past which actually we have just launched another part to that of the books interface which is where these books in Māori that we've been working on can be found.

So there’s now a whole separate section where people can look at books. But to find this information I found, I just did a little search, I narrowed it down to papers from that part of the country.

Because unfortunately, we don’t have, there is Rātana newspaper, but we don’t have all the copies and it’s just made me think there actually is a project to look at that and talk to the Church archives and see if we could, or perhaps someone is digitising that, but that’s where I thought of looking. But I thought well I’ll look at the other papers and amazingly, the Manawatu Standard — someone from the Manawatu Standard did a huge article that to print took me eight pages. And this was a great big in-depth feature. Obviously, this person understood Māori or had access to someone who did.

All the other references were to how many crayfish were on the trucks that were seen arriving. You know, what people were eating. But this one went into the detail. There were these speeches when the minister arrived. And then these two little bits that tell us really what was going on that led them to produce this little printed pass.

Mr T W Rātana then extended a welcome to Mr Veitch saying, I desire to support all the sentiments already expressed. I desire to bring before your notice the Treaty of Waitangi. Is the Treaty of Waitangi still in existence, or has it fallen into abeyance. If the treaty is still effective then I humbly ask that the promises made be fulfilled.

Then his answer, the Honourable Mr Veitch said, ‘my answer to the question of the Treaty of Waitangi is this: that it is still effective. Governments may not have kept it to the letter but the fundamental principals have been adhered to.’

So, that really does match what was in this little pass. And they obviously thought that was such a significant thing that they had this little card printed for that.

When I looked at this and thought, well that’s 1929 to 1930, there weren’t even the commemorations. The commemorations began in 1934.

Two years after Governor General Bledisloe and his wife bought the Treaty House and gave it to the country. And it’s, just as a reminder, well, A it’s interesting that Rātana had these commemorations at Christmas, not in January, and I wonder when that changed. But it’s kind of a reminder that Rātana has always had this political side to it.

You know when people say, ah, this kōrero about the Treaty is quite recent. Rātana, certainly, were talking about this very early on, before even the country was commemorating Waitangi Day.

Seán McMahon: And it did access a lot of people there, if there were over five thousand people on one day. Or twenty thousand people over the whole time.

Paul Diamond: Community Māori leaders at the time really saw this as a threat because it was really mobilising, you know 36% of the whole population.

Seán McMahon: Fantastic

Paul Diamond: All from that little wee card, that Barbara Lyon added to the collection when she spotted it at an auction in 2013.

Seán McMahon: And does it cover the Rātana bands? Because that’s usually covered in these media things because it’s such a well-known, is it the brass band? Such a well-known band.

Paul Diamond:Yes, that’s a real feature. There are different bands from around the country and then they all go to Rātana. I remember when I went to Rātana to cover one of these days for Māori Television and for Radio New Zealand, I didn’t really understand that when these people identify as Te Iwi Morehu, that almost sits above their tribe.

Cause I’d say: Where are you from? And they’d say: Te Iwi Morehu. And I’d say, no, no, where are you from? No, Te Iwi Morehu.

Then they’d say, oh, oh Ngāpuhi. But actually it’s an incredible pan-Māori thing. The temple I think had only just opened. In January that year. The Te Temepara Tapu o Ihoa, the Holy Temple of Jehova. That really distinctive temple that’s there that a lot of the other temples are kind of similar in design to, with the two towers. That had opened in January.

So this is really, this movement is just sort of really growing in strength and doing all these incredible things. And it’s a shame that newspapers back in 1930 didn’t have by-lines. I guess it might be possible to tell, the Manawatu Standard. I guess that’s what became the Evening Standard, because it’s wonderful to have that and it’s wonderful that we have it on Papers Past.

Seán McMahon: Absolutely. Well, kia ora.

Paul Diamond: Kia ora.

Seán McMahon: And so, getting near the end of the session now and I thought I’d just ask each of us what we’ve planned for Christmas Day. I’m getting an appetite now for food and beer and going swimming actually, from what I’ve heard so far.

Paul, what are you up to?

Paul Diamond: Well, just talking about New Zealand Christmases and things. I’ve had two partners who are from the northern hemisphere, and I know they’ve found our Christmases really disorienting. Because it just doesn’t feel right.

And I know when I was in Germany for Christmas one year, where everything happens on the 24th — that’s the day, the evening. They have this crazy scramble to get everything ready because they have their big dinner and presents on the 24th. And it’s winter.

I found it amazing and interesting, but it did feel odd to me. And I think it’s what I like about our Christmases is that we’re developing our own traditions.

Seán McMahon:: Yeah, absolutely.

Paul Diamond: And I think the red robin, bobbing along — he’s gone now — in the snow. We are developing our own traditions. We’re developing our own traditions about what we eat. But actually, I think, a lot of people, after the year we’ve had, will be just kind of quite happy to sit and read and eat chocolate almonds really.

Seán McMahon:: I think so, yeah. [Laughs]

Paul Diamond: And drink champagne. [Laughs]

Seán McMahon:: Yeah, yeah. Well, not much travelling going on.

Audrey?

Audrey Waugh: I think our Christmas this year is going to follow that classic Christmas on the beach song. I don’t know if anyone’s recalls? But one of the lines is, ‘Pack your picnic hamper up, we’re gonna have a feast’.

Seán McMahon: Fantastic! [Laughs]

Audrey Waugh: So, up to Waikanae Beach. Pack the dog in the car. Go up to see my family up there. I think, yeah it’s really all about coming together. The food is always going to be a feature. But just, kind of recognising that we’ve been through quite a challenging time. And it all comes down to the connections we have. Whether it's your family, your friends. Go out and reconnect, whether it's on Zoom or in person. Give someone a big hug.

Seán McMahon: Yeah, I think so. Everyone deserves a big hug after this year.

Ulu, you’ve touched on it already but have you got any further things you want to share on your Christmas.

Ulu Afaese: Nah, I think we’re just planning to drive around on Christmas Day. Church, obviously, is the main thing. But yeah, just looking forward to.. my mother-in-law’s an awesome cook. [Laughs]

Seán McMahon: : [Laughs]

Ulu Afaese: And yeah, I’m always the greatest sous chef. Yeah, so…

Seán McMahon: [Laughs] It’s the best place to be in the kitchen, cooking. Because you get to taste everything before it goes out.

Audrey Waugh: Lick the spoon. [Laughs]

Ulu Afaese: And I noticed too, probably for everyone, how there’s always a barbeque expert comes out of nowhere and wants to criticise how you’re cooking stuff. [Laughs]

Nah, just a quiet one. Still a massive feed. Church.

Seán McMahon: Yeah, that sounds good. That sounds wonderful. Yeah, so for myself I guess, I’m going up with my wife and kids to Dannervirke. Into the heartland of New Zealand. And so we’ll be celebrating Christmas up there. Which is always fun. Southern Hawke’s Bay, so you usually get good weather there. Maybe get to church, Catholic church on a Sunday. Whatever day it is, Saturday isn’t it, I think, this year Christmas Day.

I guess for me, it’s like the Irish thing, St Stephen’s Day, or as you call it in New Zealand, Boxing Day. It’s a big day for racing, and I sort of come from a racing family so. You have that eating on the Christmas Day, and the chair, but you’re sort of in anticipation that the next day is when it happens. And so, you sort of do the family thing. Then the next day is St Stephen&’s Day, is Boxing Day, comes around and then you’re off. Pubs open at twelve or whatever. You’re on the race track. It’s the start of the real Christmas thing. Like Paul was saying, in the north you have your Christmas, but then you’re back to snow and it’s cold. And you have nothing to look forward to.

Down under it’s the start, we’ve got this whole summer ahead of us. Christmas Day’s finished, we’ve had our obligations, and we’re free.

Paul Diamond: I remember one of my grandfather’s going to the races, on Boxing Day. But I’ve also heard jokes about Germans who come here and they go: ‘And when is the boxing?‘ [Laughs]

It is a bit confusing.

Seán McMahon: I know [Laughs]

What I never knew, is in Ireland it’s the saints, it’s Saint Stephens it’s sort of obvious. But I gather Boxing Day means is the day after when you’ve unwrapped your presents and you’re putting away your boxes that the presents came in. And you know the term, box room. Well a box room is a spare room in the house where you store your boxes. So I think that is where it's come from.

I hope I’m not making that up. I should've done my research, I must talk to a journalist.

Audrey Waugh: Get a fact check on that one. [Laughs]

Seán McMahon: Get a fact check on that one, yeah, yeah. [Laughs]

Paul Diamond: We do know it’s not about boxing.

Seán McMahon: It’s not about boxing! No, no, my god. Well, I’m sure there are occasional fisticuffs in some families when they’ve had too much to drink.

Ulu Afaese : Maybe we should establish that that’s the original Black Friday. Boxing Day’s the original. I mean I’ve heard many of like.

Paul Diamond: Ah, the sales.

Ulu Afaese: Family friends and that, they actually get their Christmas gifts on Boxing Day.

Yeah, yeah, I just want to establish that.

Audrey Waugh: Or return all the presents. [Laughs]

Ulu Afaese: Sorry to Jay, he’s American. But yeah, Boxing Day’s the original Black Friday in this country. [Laughs]

Seán McMahon: Return those presents. [Laughs]

No, keep the presents, keep the presents.

Okay, well I’d like to thank everyone for turning up again for this Christmas edition. Unfortunately, Mary couldn’t be with us today. She’s my co-host, but she’s unable. So, we miss you Mary, you would’ve loved this. But thanks too, Mary, for all the work she’s done during the year.

And to Jay, I’m looking across. He should have a microphone. We can’t interview him because there’s one microphone down. But Jay, for all your wonderful work as a sound engineer for the year. That’s fantastic.

Aaron Wanoa, who’s our producer, he’s also away today and can’t make this. Shout out to you for all the work you’ve done.

And to Ulu, Paul and Audrey. Thanks for coming along.

Ulu thank you for your podcast during the year. We did two this year and you’re one of them. That was a fantastic one you gave during the year. Lovely to have that.

Ulu Afaese: Chur.

Seán McMahon:And then Paul of course, you were here last year. We’ve had you on, you were the first, the first one we had on Pūkana.

Audrey, back again this year.

Audrey Waugh: Becoming a bit of a tradition now isn’t it.

Seán McMahon: Hopefully we’ll see more of you in the new year.

So the podcast will be back next year. We’re just having… The pilot is finished so we’re putting through a case for the podcast to be, business as usual. We might grow the team, so we might include people like Audrey and other people who are interested, to join the team and make it bigger.

We’re also working with Sam’s New Zealand Digital team to build the RSS feeds. So we’re hoping early next year we’ll have a feed which will then mean that we have the show on the website, but we also have it on Spotify, Apple and Google and wherever else we need a third party. So that’s gonna be a big thing for us next year.

So, have a great Christmas everyone. Be safe, look after yourselves. Mind the COVID.

And as a treat the music this year is a piece from the Turnbull Library choir, aka the Horsburgh. And this year we’re going out on a song you may have heard, a Pukeko in a Ponga Tree, which is written by Kingi Ihaka in 1981. And of course it’s taken from the original song. And so, this is the version from our choir.

So look after each other. Kia kaha. And ka kite ano!

(Music)

Fereni Ete with the babies who appeared in her Christmas play, 1995, by Ray Pigney. Ref: EP-Ethnology-Polynesian-02. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Whitcombe and Tombs Limited, Cashel St, Christchurch, 1886. Ref: Eph-C-PRINTING-1886-01. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Ephemera of octavo size relating to Samoa. 1970-1979. Ref: Eph-A-SAMOA-1970s. Alexander Turnbull Library.

He Paahi Whakamaharatanga, Ratana Pa, 1929. Ref: Eph-A-MAORI-Ratana-1929-01. Alexander Turnbull Library.

The Turnbull Choir who sang for this podcast.

Mentioned in the podcast

Ephemera of octavo size relating to Samoa. 1970-1979 — Christmas card and tourism pamplets from Samoa.

Fereni Ete with the babies who appeared in her Christmas play — photograph

The end of the golden weather:a voyage into a New Zealand childhood by Bruce Mason — Segment is from “Christmas at Te Parenga”

Whitcombe and Tombs Limited, Cashel St, Christchurch — advertisement for Whitcome and Tombs Limited

He Paahi Whakamaharatanga. Ratana Pa — memorail card for hui at Rātana Pa.

Music references

‘Funiculi Funicula’ — podcast intro theme song. The final track on from Keil Isles album ‘Take Off’.

Pukeko in a Ponga Tree — Closing music in podcast.

Archive of New Zealand Music — the Archive of New Zealand Music is the world's largest archive of unpublished material relating to New Zealand music and musicians

Library Loudhailer podcast

This recording is an episode from The Library Loudhailer podcast.

Use the comments below to send us your questions and feedback – we’d love to know what you enjoyed (or didn’t) and what else you’d like to hear about.

Theme song — Funiculi Funicula the final track on from Keil Isles album Take Off.