Encountering Mīharo | Travel light

The 30 students in the MA (Creative Writing) workshops at Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters visited Mīharo Wonder. Our ‘Encountering Mīharo’ blog series will share students’ thoughtful and eclectic responses.

Writers encounter Mīharo Wonder

Wonder is a place where writing often begins — and each year, during the first six weeks of the MA in Creative Writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters, we set exercises designed to unlock the kind of wondering unique to each writer. In April 2021 we brought the MA students to the Mīharo exhibition in the hope that some of the resonant objects, images and artefacts might prompt stories, poems or essays. We gave them no brief other than to choose an exhibit and pursue the lines of imagination it prompted.

For these writers, encounters with the past have become acts of invention as well as recovery and re-evaluation. The exhibition becomes an observatory in which old stories give birth to new, the past is encountered with fresh eyes and transformed through the lens of the present. The writing presented here is only a sample of the work produced, and we imagine work by other writers will come to fruition in future. We’re grateful to National Library staff Peter Ireland, Anthony Tedeschi and Fiona Oliver for providing additional insight and background to the exhibition and to Mary Hay and Jay Buzenberg for publishing the student’s work on the website. And we hope you enjoy the wondering Mīharo has produced.

Chris Price, Tina Makereti and Kate Duignan

"While Mīharo Wonder is moored to the walls and arrested in its cases, its imaginative scope ranges freely – here is the best possible evidence of that." — Peter Ireland, Mīharo Wonder co-curator

Travel light | Joe Parker

26-05-69

Istanbul, Turkey

The freaks meet at The Pudding Shop. Long-haired Westerners in bright, foreign clothing, Indian saris and Moroccan djellabas. Drinking sweet black coffee and getting stoned. A wall is littered with notices of all kinds, offers of travel and requests for rides, messages for friends and lovers.

Gentle soul looking to go East with funky pilgrims.

3 2 1 SEATS LEFT IN THE PEACE MACHINE!!! CHRISTMAS IN CALANGUTE!!!!!

Ruby T! Meet us in Tehran!

Most of them speak of a place that’s more of a yearning than a direction. India, India, India, they say, and I sit with my too-strong coffee and my tavuk göğsü, pastry chicken topped with cinnamon and sugar, and I repeat the word under my breath like a prayer.

I should be frightened. A woman travelling alone, a stranger in a strange land. But the thought of India wraps itself around me. She hooks my finger in hers and leads me forward, and I am not afraid.

04-06-69

Cappadocia, Turkey

I spend two nights in a cathedral made of stone.

Matthieu brought me here. We met on the dolmuş between Istanbul and Ankara, and he shook his head at my intention of making my way straight to the border.

‘You cannot miss this country,’ he said. ‘India will always be there.’

He’s a soft man, with moth-like hands and a smile that hides his teeth. ‘They grew badly,’ he said unasked, when he saw my glance at his lips. ‘Their roots were never strong.’ I followed him to Kayseri, and again to Göreme where we bought food to last us, and then we hiked out together amongst the fairy chimneys.

That’s what they call them, these towers of stone. Rising high from the pebbled sand in layered turrets, a community of slow growth ending in sharp peaks. I saw openings in the towers as I walked, ancient doors and windows cut into the soft volcanic rock—some were decorative and complete, facades of pillars and engraved entrances, while others were little more than squares of darkness. Matthieu led me on a goat’s path through boulders and I felt the grating pull on my palms as I climbed. We came to an entranceway, a roughhewn opening between the rocks, and we stepped through into the church.

A long, open space, seats carved between the floor and the walls. A stone table rose from the ground—an altar once upon a time, I thought—and the front of it opened out to the valley, fifty feet above the ground.

‘Beautiful, yes?’ Matthieu said, and laid his hand upon the altar.

Now we sit, and eat bread and cheese and dates, olives dripping in oil. We drink peppery Turkish wine as we lead each other gently down our family trees.

I tell him of my mother, how people say I carry her resemblance but that I can never see the likeness in the photographs I have of her, and how that seems worse, somehow, than my motherless childhood. I tell him of Hāwera and the mountain, and my father’s dreams—the way he shouts and weeps in the night, yet in the morning speaks about capturing Padua so proudly he might have been personally responsible for Hitler’s suicide.

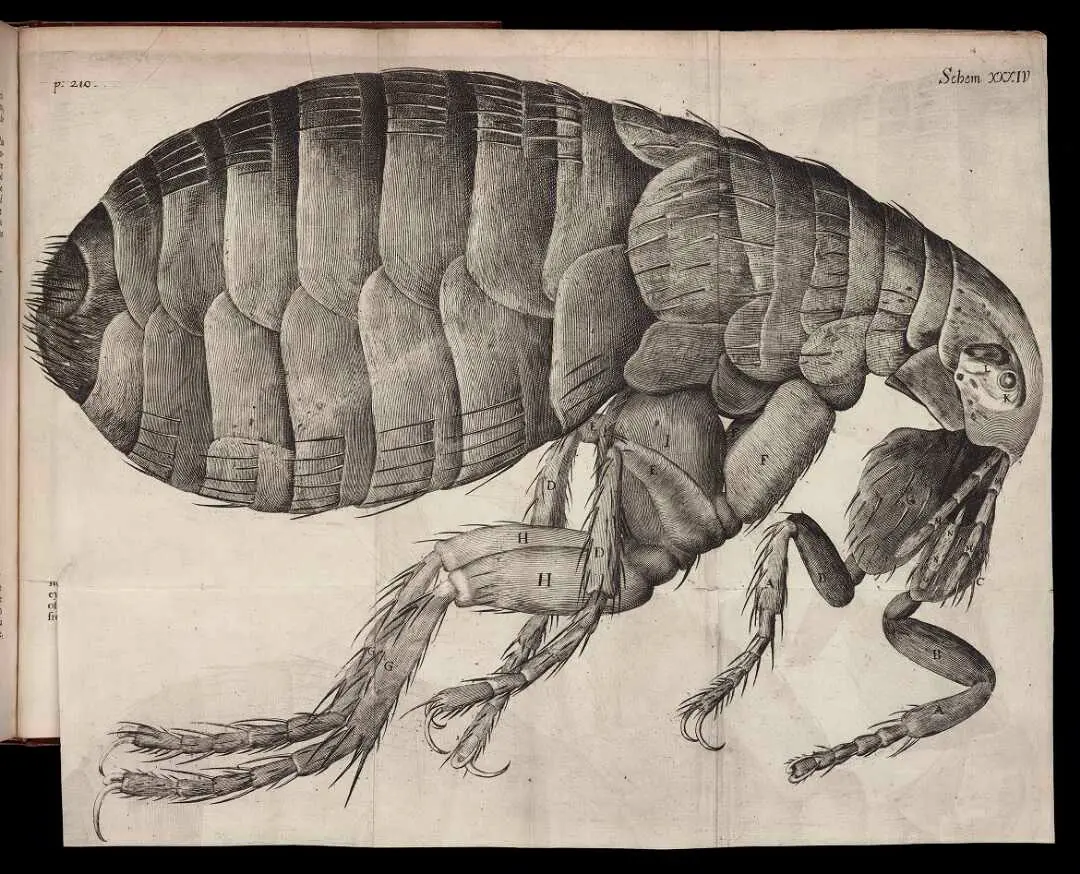

In response, Matthieu shows me an old postcard. It’s black and white and torn at the edges, stained with past tears or the drinks that washed them away. The postcard shows a flea, of all things—a print of a copperplate engraving, he says, which in turn came from a drawing—and I expect to be repulsed until I look closer. The delicacy of the strokes pulls me in. It’s a flea, only a flea, but it is elegant, exquisite.

‘From Hooke’s Micrographia,’ he says, and although I don’t know the name it brings to mind dusty books in dusty classrooms. ‘Robert Hooke looked through a microscope and drew what he saw by hand. It was the first time most people had properly seen these creatures. How beautiful they can be. My father was a scientist, a biologist, and he loved Hooke. Nobody imagined that a flea might hold beauty, he told me. He gave me this print to remind me to find the beauty in small things.’

The back of the card holds a scrawling in French which I cannot read.

I lie awake for a long time, listening to Matthieu’s snores, feeling the rock beneath my back. Centuries are pressed into this stone like flowers in a book. I imagine slipping that postcard from his bag, concealing it on my person. Making off into the night. I imagine sitting, breathing air that tastes of cumin and mint, absorbing the lines of the drawing like a drug beneath the stars.

14-06-69

Tehran, Iran

The women here wear beauty like fragrance. In my dirty clothes and dusty boots I feel small and unwashed, a roadside attraction. They sit at cafés in the city centre, their legs long and sun-bronzed beneath their short skirts, their blouses stylish and colourful.

I left Matthieu in Doğubayazıt, beneath the shadow of Mount Ararat. I wanted to press forward; he intended to climb the mountain to see if he could find the Ark, any lonely creatures that Noah had left behind. I thought of him returning triumphant on a woolly mammoth, a unicorn, a dragon coughing fire. I hugged him goodbye.

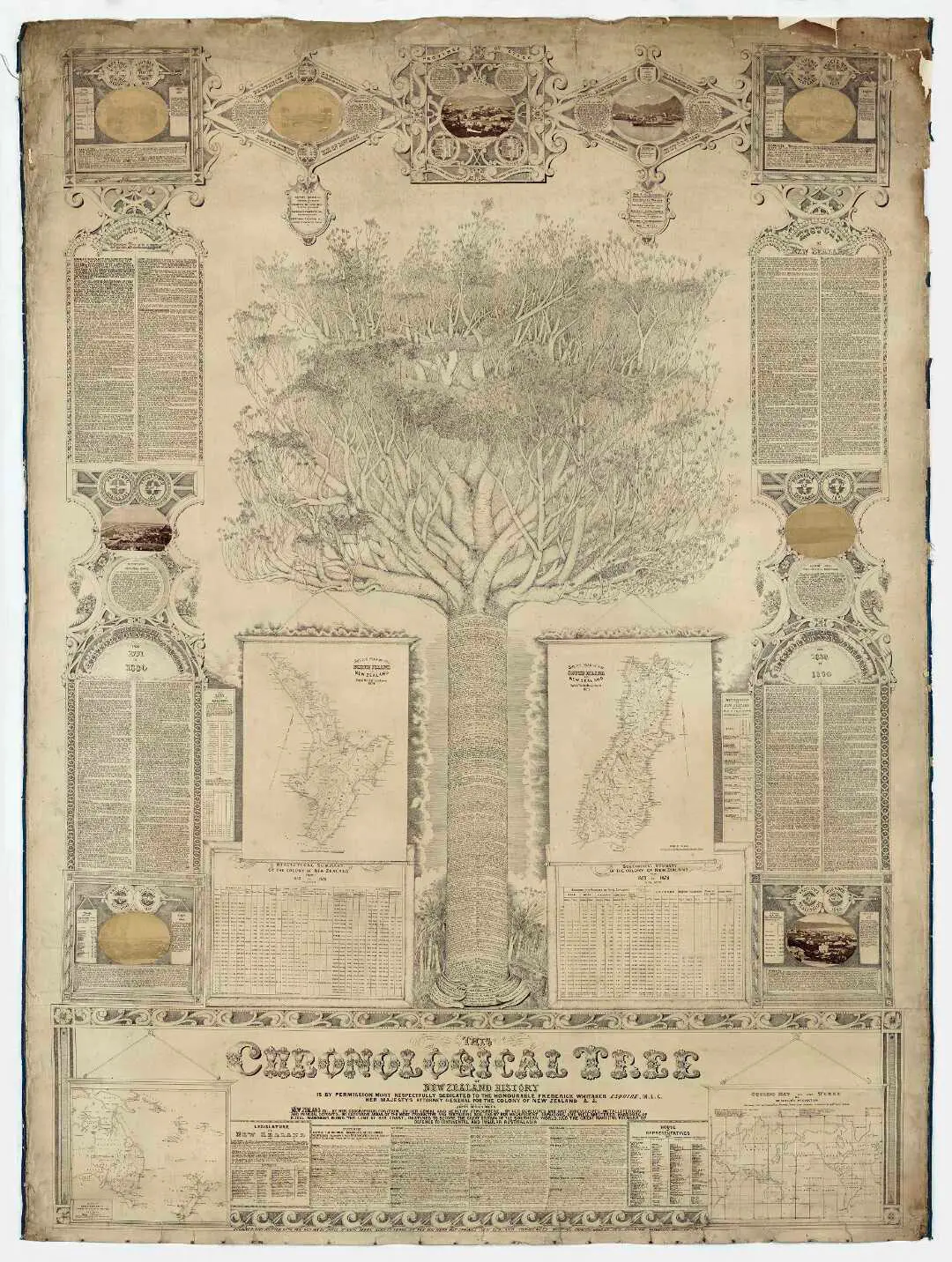

Yesterday, a couple in a park noticed Siddhartha in my hands and told me of the Bodhi Tree; an ancient, sacred fig tree in India, where Buddha attained enlightenment. They call it the Tree of Awakening, of Understanding, they said.

I understand that I am very jealous of the women here and will not be staying long.

29-06-69

Kabul, Afghanistan

On my first night in this country, I was offered a wheel of hash as a starter in a restaurant.

This is a place of wide-open spaces. Green valleys and fields of apricots, mountains rising up from the lush growth below, brown slopes naked but for the lashings of snow at the peaks. The rivers are olive and blue and yellow with silt. The air smells of pomegranate. Everyone smiles at everyone.

The hotel I’m staying at is small and dingy and has extracted any romanticism I may have developed towards fleas, but there’s a rooftop terrace that overlooks the city. The other guests congregate there and I join them as the sun goes down, sit on a red cushion and listen to a girl singing a song about San Francisco—choosing the song, perhaps, because of the flower in her own hair. A man leans in beside me, his pupils like black holes; I feel his breath on my neck as he tells me about Morocco, how he spent a year dancing with the Sufis. He speaks of mint tea but calls it Berber Whiskey, describes how the old men sit in cafés facing the street and talk through rotted teeth, all that sugar. They serve it from silver teapots, he says, held high above the glass—the teapot is the sky, the glass is the earth. The tea rains down and replenishes.

‘A woman read my fortune in the Djemaa el-Fna,’ he says, swaying a little, and scratches at the infected sores on his forearm. They aren’t bedbug bites, I realise. ‘She broke an orange with her fingers and saw my future in the juice on my palm. She said that I would meet a girl, and that the girl would chase out the seven devils inside me.’

I move cushions. Mercifully, he passes out shortly afterwards.

Others are singing, now.

05-07-69

Rawalpindi, Pakistan

Pakistan is dull and conservative and so very different to Afghanistan, and I pass through it quickly.

There’s a part of me that wonders why I am here. I compile lists in my mind, trying to find a meaning, a purpose—for these strange clothes, these nights spent with long-haired men, with women whose bare feet are as dirty as my own. I’ve been down so long it looks like up to me. Am I following my life to its branches, spreading myself out amongst its leaves and listening for God in the rain? Or am I sinking, melting myself deep into the ochre earth of my roots and listening to the tendrils of my childhood, hunting whispers from lives before? This is who you are, Astrid, I imagine those whispers saying. Here are your forgotten sacraments, your testaments of births and dreams and deaths long past. Here are your broken promises.

22-07-69

Goa, India

I made it. My toes are warmed by the ocean. I collect shells on white beaches and drink cashew nut feni in the sun.

I look back through these pages and think, of all things, of Matthieu’s postcard. A gift from a father. A small slip of cardboard, four by six inches. It will fade, and rot, and turn to nothing before too long, yet it holds a world within it. I think of Robert Hooke and his microscope, his careful devotions of art and science. Perhaps that is all a diary is—a way of looking at your life through the lens of old-fashioned pen and paper, marking down and making clear all the things you cannot see. A way of following the lines of your own Bodhi Tree; your Tree of Understanding, your Tree of Life.

Images that inspired this piece

This piece was inspired by three items in the Mīharo Wonder exhibition. Two illustrations from 1667 and 1876 as well as a diary written in 1979.

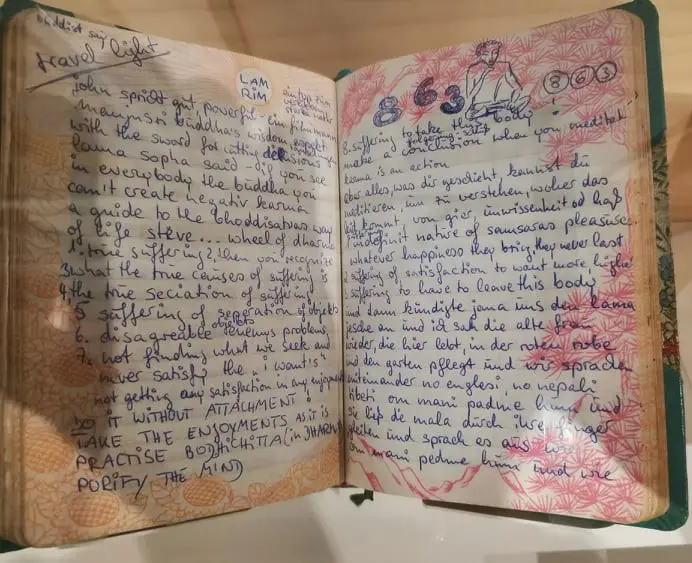

Diary, Astrida Dahm, 1979-1980. Ref:MS-Papers-7904-1. Alexander Turnbull Library. Photo by Joe Parker.

Diary, Astrida Dahm, 1979-1980. Ref:MS-Papers-7904-1. Alexander Turnbull Library. Photo by Joe Parker.

Illustration from Micrographia:or Some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses. With observations and inquiries thereupon. By R. Hooke, Fellow of the Royal Society..Micrographia. Robert Hooke, 1635-1703.

Illustration from Micrographia:or Some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses. With observations and inquiries thereupon. By R. Hooke, Fellow of the Royal Society..Micrographia. Robert Hooke, 1635-1703.

Visit Mīharo Wonder in the gallery and online

Experience the Mīharo Wonder online exhibition

Read the Encountering Mīharo blog series

Read the Mīharo Wonder blogs

Visit Mīharo Wonder at the National Library in Wellington

Thanks to Alexander Turnbull and the National Library for preserving this historical object.

McKain Meek was the elder brother of one of my Great Grandfathers, who had an interesting and highly varied career in NZ and Australia. One other of his large maps, produced in 1861, is preserved in the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, known as Meek's Atlas. It won first prize in an Australian international exhibition in 1861, then was sent on to the 1862 London International Exhibition.

Further details are in a blog on the State Library of Victoria's website.

I'm looking forward to visiting your exhibition tomorrow.