'a series of Heavens': Katherine Mansfield in her own words

Excerpts from the recently digitised notebooks of Katherine Mansfield. Now available online, the notebooks are an invaluable primary source for Mansfield researchers and help reveal, in her own words, the author’s innermost thoughts on life and writing.

Letter to Elizabeth von Arnim, 1922

I haven't written a word since October and I don't mean to until the spring. I want much more material; I am tired of my little stories like birds bred in cages...

Goodbye, my dearest cousin. I shall never know anyone like you; I shall remember every little thing about you for ever.

— Katherine Mansfield, letter to Elizabeth von Arnim, December 31, 1922. The Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield, Chaucer Mansions flat, Queen's Club Gardens, West Kensington, London, England, 1913. Ref:

1/4-059876-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Nine days after penning this letter Katherine Mansfield died at the age of thirty-four, after a long struggle with tuberculosis. She had published three collections of stories. The posthumous publishing and critical appraisal of her work began almost immediately.

Within a year her widower John Middleton Murry had combed through Mansfield’s papers for Poems by Katherine Mansfield. Then came Journal of Katherine Mansfield (1927), The Letters of Katherine Mansfield (1928), and The Scrapbook of Katherine Mansfield (1939).

It was, as the New York Times noted, ‘an astonishingly successful posthumous publishing venture’, wrapped up in Murry’s gushing praise for ‘the most wonderful writer and most beautiful spirit of our time.’

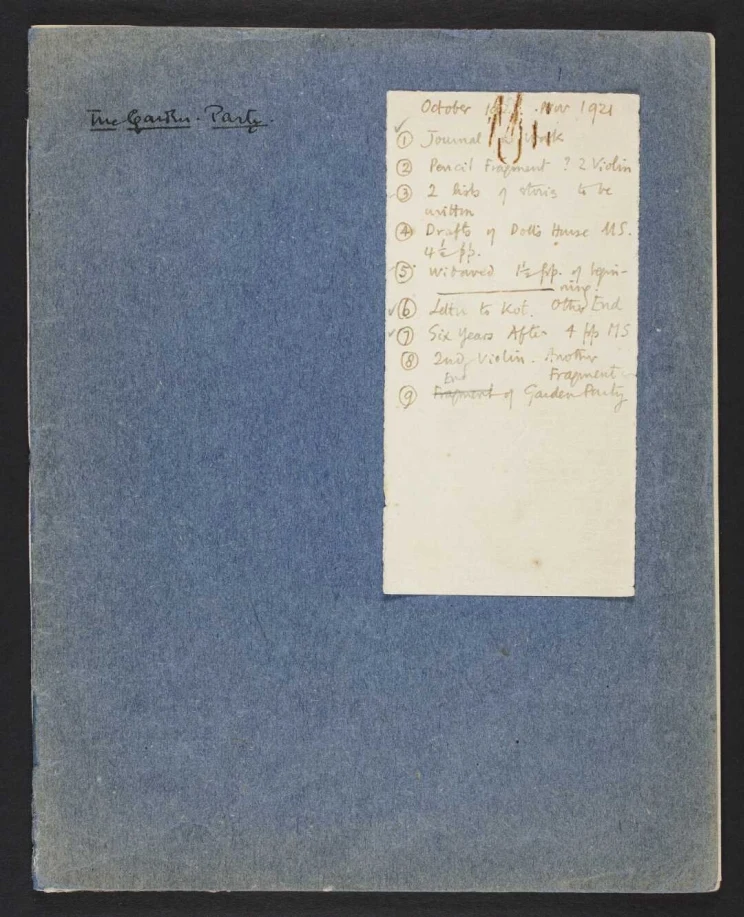

Cover of Notebook 41. Ref: qMS-1277. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Extract from Notebook 30, 1921

Now, Katherine, what do you mean by health? And what do you want it for?

Answer: By health I mean the power to live a full, adult, living breathing life in close contact [with] what I love – the earth and the wonders thereof, the sea, the sun. All that we mean when we speak of the external world. I want to enter into it, to be part of it, to live in it, to learn from it, to lose all that is superficial and acquired in me and to become a conscious, direct human being. I want, by understanding myself, to understand others. I want to be all that I am capable of becoming so that I may be – (and here I have stopped and waited and waited and it’s no good – there’s only one phrase that will do) a child of the sun. About helping others, about carrying a light and so on it seems false to say a single word. Let it be at that. A child of the sun.

— Extract from Notebook 30, qMS-1276

Murry’s portrayal of Mansfield as something of a secular saint invited significant criticism, but he wasn’t the only one to see Mansfield as a tragic figure – tremendously gifted and ultimately doomed. Virginia Woolf, oft-quoted in her appreciation of Mansfield’s writing – ‘the only writing I have ever been jealous of’ – later wrote that Mansfield was ‘forever pursued by her dying’.

Perhaps the enduring appeal of Mansfield’s life story revolves around the varying interpretations of her remarkable character. There’s Murry’s portrayal of a faultless genius, Mansfield the daring modernist, Mansfield the colonial outsider, the acerbic wit, the feminist rebel, the greatly under or over-appreciated talent.

What is clear is that Murry’s posthumous publishing of Mansfield’s papers, which so helped inform earlier interpretations of her life and work, was highly selective and riddled with mistakes.

Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry, Chaucer Mansions, Kensington, London, 1913. Ref: 1/2-028643-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Notebook 30, 1921

‘Lives like Logs of Driftwood’. Etc.

Begun September 27th, 1921.These pages from my journal. Don’t let them distress you.

The story has a happy ending – really and truly.— Beginning of Notebook 30, qMS-1276

Amongst the written material Mansfield left behind were fifty-three handwritten notebooks, dating from 1903 until her death twenty years later. The notebooks contain a huge range of material – jotted thoughts, memories, drafts, lists and observations.

In 1957 the Turnbull Library bought the bulk of Mansfield’s personal papers from Murry, who died the same year, and further substantial acquisitions were made from Murry’s heirs in 1972/3 and 2012.

The Turnbull holds forty-six of Mansfield’s notebooks, with copies of the remaining notebooks, held in the Newberry Library of Chicago, available in the Turnbull on microfilm. The notebooks form a central part of the Turnbull Library’s renowned Katherine Mansfield collection, and are recognised as highly significant heritage materials by UNESCO’s Memory of the World register for New Zealand:

The Katherine Mansfield Literary and Personal Papers inscribed into the UNESCO Memory of the World register for New Zealand.

Digitising Mansfield’s notebooks

After substantial recent work to re-assess the conservation needs of the manuscripts and move them into improved long-term storage, digitisation of the notebooks began in 2020. All forty-six of Mansfield’s notebooks held in the Turnbull Library are now available online and are preserved in the National Digital Heritage Archive, as are an increasing number of unbound Mansfield papers.

Digitisation increases the accessibility of heritage collections for the research community, allowing access to library materials from across New Zealand and the world. Digitisation also helps to reduce physical handling and the resulting deterioration of fragile materials.

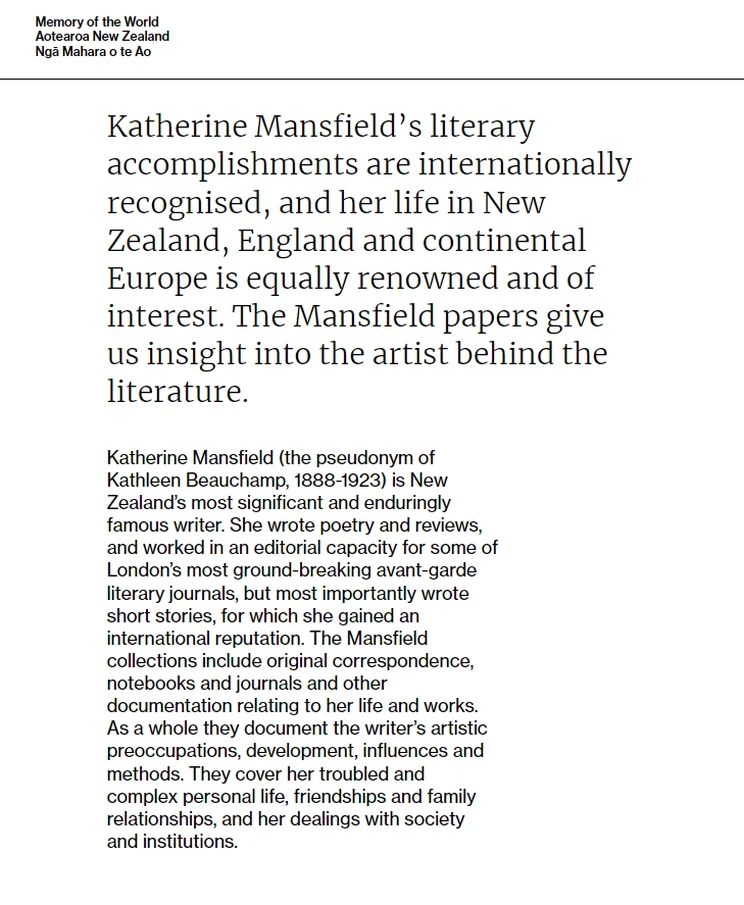

Two loose pages from Notebook 34, May 1915 - March 1916. Ref: qMS-1252. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Some of the text reads:

‘…the amount of minute and delicate joy I get out of watching people and things when I am alone is simply enormous—I really only have ‘perfect fun’ with myself… Other people won't stop and look at the things I want to look at, or, if they do, they stop to please me or to humour me or to keep the peace. But I am so made that as sure as I am with anyone, I begin to give consideration to their opinions and their desires, and they are not worth half the consideration that mine are…I feel quite content to live here, in a furnished room, and watch… Life with other people becomes a blur… but it's enormously valuable and marvellous when I'm alone, the detail of life, the life of life.’

The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks

An invaluable tool for anyone interested in the Mansfield notebooks is former Turnbull manuscripts librarian Margaret Scott’s The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks, the result of a monumental task of transcribing hundreds of pages of Mansfield’s infamous handwriting.

Scott called Mansfield’s fifty-three notebooks and associated papers a ‘huge, amorphous, nearly illegible mass of material… the raw material for an infinite number of investigations.’

It is only now, with the publication of Margaret Scott’s complete and unselective transcription of the material bequeathed to Murry, that we can really see Mansfield, off her guard and unexpurgated, for the first time… Mansfield’s notebooks are remarkable, touched by a sense of the underlying pathos of things, two parts tragedy and two parts comedy.

— The Times Literary Supplement

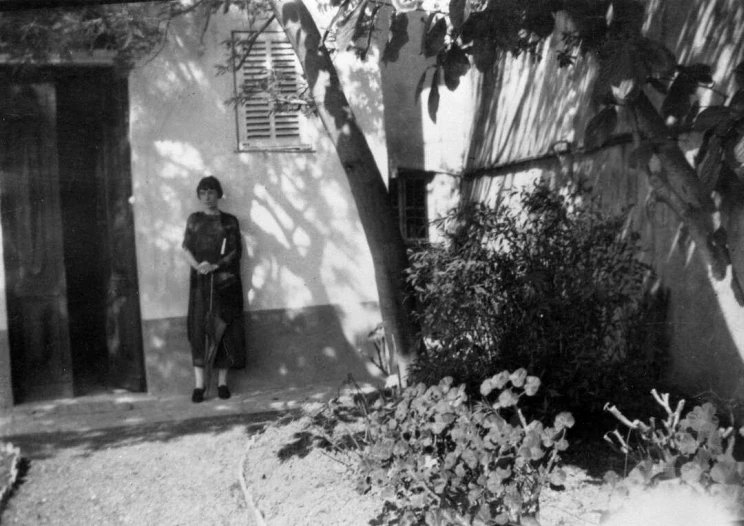

Katherine Mansfield standing in the garden at the Villa Isola Bella, Menton, France, 1920. Ref: 1/2-011914-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

What would Katherine Mansfield think?

Amongst all the publishing, articles, interpretation and re-interpretation of Mansfield’s work and life, there’s a particular thrill to these original texts. What would Mansfield herself have made of this kind of access? In 1915 she wrote of keeping ‘a kind of minute note book – to be published some day. That is all. No novels, no problem stories, nothing that is not simple, open.’ Maybe we have a particularly personal and unpolished first draft.

The notebooks are the closest thing we will ever have to Mansfield’s innermost thoughts on life and writing. Most revealing, perhaps, are the moments when Mansfield felt the urge to record her own longings. A recurring theme through the later texts is one of Mansfield’s own literary idols – with whom she felt great affinity – the fellow short-story writer Anton Chekhov, himself a sufferer of tuberculosis, who died in 1904 aged forty-four:

Tchekhov [sic] made a mistake in thinking that if he had had more time he would have written more fully, described the rain & the midwife & doctor having tea. The truth is one can only get so much into a story; there is always a sacrifice. One has to leave out what one knows & longs to use. Why? I haven’t any idea but there it is. It’s always a kind of race, to get in as much as one can before it disappears.

— Extract from Notebook 20, qMS-1282

Ach, Tchekhov! Why are you dead! Why can’t I talk to you – in a big, darkish room – at late evening – where the light is green from the waving trees outside. I’d like to write a series of Heavens: that would be one.

— Extract from Notebook 12, qMS-1260

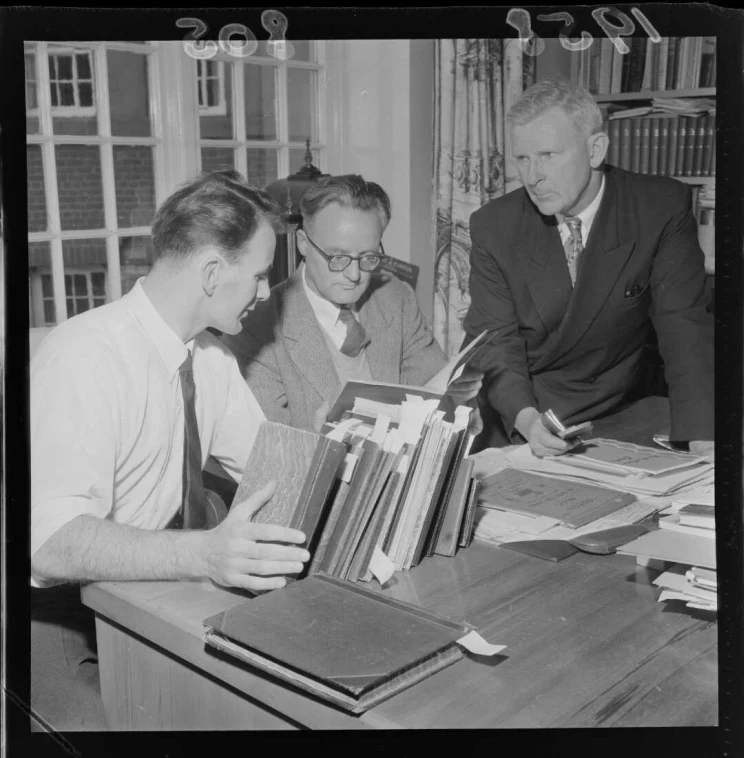

Manuscripts curator, Glen Barclay, Professor Ian Gordon and Chief Librarian, Mr C R H Taylor, looking at the journals of Katherine Mansfield, which have just arrived at the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, 1958. Ref: EP/1958/0805-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Further reading

Reference materials

The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks, Katherine Mansfield, Margaret Scott (ed.), University of Minnesota Press edition 2002.

The Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield, Margaret Scott and Vincent O’Sullivan (eds.), Oxford University Press, 1984-2008.

Wild Places: Selected Stories by Katherine Mansfield, with texts by Helen Simpson and Claire Harman, Random House, 2023.

The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield, with text by Ali Smith, Penguin, 2007.

Whistling in the Dark, Patricia Hampl, The New York Times, March 16, 2003.

Very Free and Indirect, Frances Wilson, The New York Review of Books, February 23, 2023.

Stories that simply unfold, Kirsty Gunn, The Times Literary Supplement, January 6, 2023.