High level summary of impact areas of libraries

Find out what research is currently available about the difference libraries make, and to consider which areas need to be explored.

New Zealand Libraries Partnership Programme: supporting libraries sector sustainability

This initiative is part of a suite delivered through the New Zealand Libraries Partnership Programme to support the long-term sustainability of the libraries sector in Aotearoa.

Early stakeholder engagement highlighted concerns about the time-limited nature of funding support and the need to consider ways to strengthen the sector for the longer term.

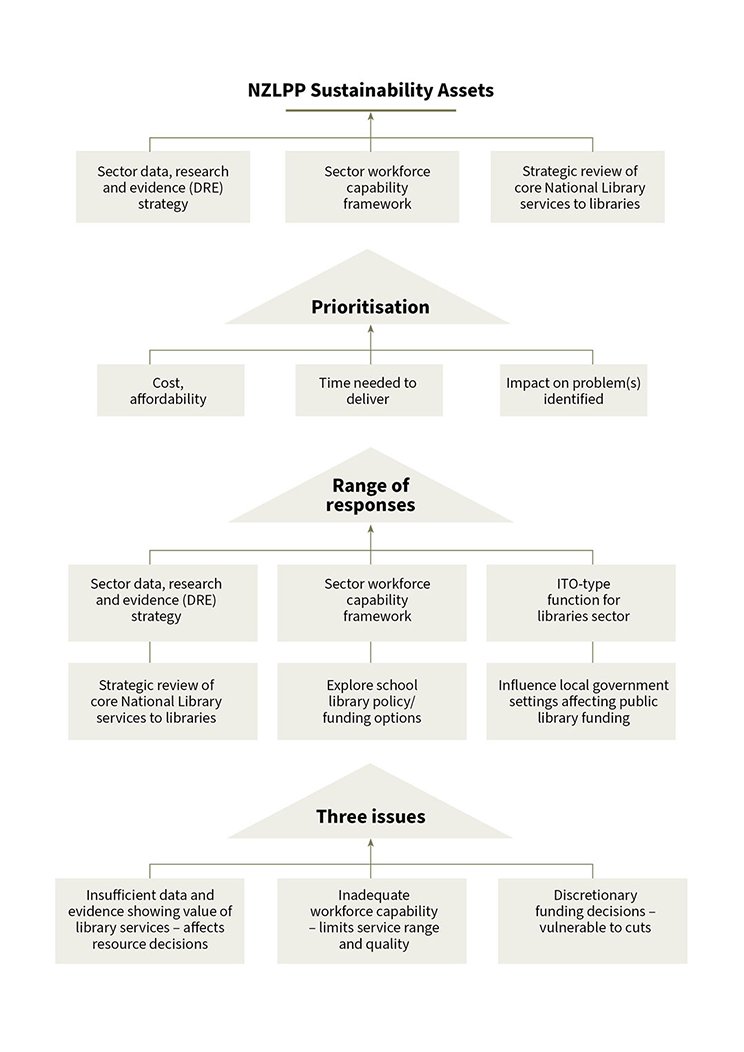

In response, the Programme carried out a structured process (Investment Logic Mapping, ILM) with experienced sector members to identify key issues that threaten the health of the sector, and potential responses. The process revealed three key problems and produced wide-ranging response options, which were then prioritised considering their relative cost, time needed to deliver and the impact on the problems identified. The resulting package of measures was widely supported by sector representatives.

The diagram on the following page shows how the ILM and prioritisation processes lead to the package of initiatives. Collectively, these initiatives will go some way towards addressing the issues identified through the ILM, ensuring library services in Aotearoa continue to evolve and thrive. Areas not yet invested in could inform any future opportunities to collaborate across the libraries sector.

Purpose

This is a living document which provides an outline of the key impact themes which were identified from a review of selected literature completed in December 2021 (see Towards a Value Proposition of Libraries in Aotearoa: Review of selected literature) and in a few instances on interviews carried out with some libraries sector representatives. The purpose of this document is to help libraries understand what research is currently available about the difference libraries make, and to consider which areas need to be explored.

The information is organised primarily by perspective (i.e., by library user; host organisation; communities, hapū and iwi; and Aotearoa society). Organising the information this way creates an opportunity for libraries to look beyond their sub-sector and to consider whether the benefits of another sub-sector may also apply to them and should be explored further.

This document is intended to be used with the Libraries Applied Impact Framework (the Framework)1 which, for ease of use, sets out key impact themes by sub-sector (see A Tool to Support Measuring Libraries Impact).

Figure 1: NZLPP outcomes (supplied by the National Library)

Long description — Investment Logic Mapping diagram

The image has four bolded headings in triangles with connecting arrows – from bottom to top: ‘three issues’, ‘range of responses’, ‘prioritisation’, and ‘NZLPP sustainability assets’.

There is information in boxes underneath each heading, as follows, from bottom to top:

Three issues

Insufficient data and evidence showing value of library services — affects resource decisions

Inadequate workforce capability — limits service range and quality

Discretionary funding decisions — vulnerable to cuts.

Range of responses

Sector data, research and evidence (DRE) strategy

Strategic review of core National Library services to libraries

Sector workforce capability framework

Explore school library policy/funding options

ITO-type function for libraries sector

Influence local government settings affecting public library funding.

Prioritisation

Cost, affordability

Time needed to deliver

Impact on problem(s) identified.

NZLPP Sustainability Assets

Library user perspective

There is a need for further research in Aotearoa that explores the difference that libraries make for tangata whenua and other marginalised groups. This would help 'shed a light' on who currently benefits from library services and is not something that can be addressed by research carried out overseas.

Due to the amount of research findings, this section is organised by sub-sector.

Public libraries

Key findings — Economic: expenditure savings

Financial savings for users

Borrowing material leads to users realising personal cost savings (Söderholm, 2016, as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021) 2

Reduced spending on leisure activities and entertainment, also accessing computers and internet for economically impacted people (OCLC, 2010)

Access to digital resources for free (ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016); it is one of the most sought after services at public libraries (Becker et al. 2010) |

Key findings — Learning and education key findings

Lifelong learning

Supports individuals to:

acquire general literacy skills

access information which supports the pursuit of hobbies

acquisition of "social, emotional, and workforce readiness skills" (Cole & Stenström, 2021, p. 488)

Role in supporting formal and informal study at all stages of life (ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016)

Capital investment in public libraries Improve children's academic achievement, especially reading) (Gilpin et al., 2021) 3

Learning and education services that are tailored to meet library user needs (disadvantaged, vulnerable groups, diverse needs incl. mental health) (Raine, 2016)

Personal development

Opportunity to generally improve themselves, including literacy, digital literacy, improving understanding of others' culture (Corble, 2019)

Create opportunities for people experiencing homelessness to engage with reading, internet access and build life skills (Dowdell & Liew, 2019

Access to information and resources

Access to books and information (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Opportunities to engage in stimulating technology workshops for children (Digital Inclusion Research Group, 2017)

Key findings — Health literacy and wellbeing (area of opportunity)

Access to health support

Well placed to provide access to health information – creating opportunity to learn and support health and wellbeing (Naccarella & Horwood, 2021; Rosenfeldt & Cowell, 2021)

Supports library users to access community agencies (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Key findings — Improved subjective wellbeing key findings

Safe space

Safe, free physical space (Stilwell, 2009)

Quiet space away from home (ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016)

Place of refuge or shelter for people experiencing homelessness (Dowdell & Liew, 2019)

Feeling better in response to a library worker making contact, providing information about emergency food supplies, health and wellbeing information during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cowell, 2020, as cited in Rosenfeldt & Cowell, 2021)

Social cohesion

Improved sense of belonging (Public Libraries Victoria Network et al., 2011)

Lifeline – facilitate community interaction, especially valuable for people experiencing social isolation (Field & Tran, 2018)

Opportunities to engage with library staff and other library users ((Sørensen, 2021)

Recreation

Access to cultural and leisure activities (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Key findings — Sense of belonging

Social and cultural value_

Auckland libraries referred to as acting as a multicultural bridge. ... information obtained from library services and programmes support people new to Aotearoa to adapt to a different sociocultural system (Lim & Boamah, 2019)

Reduce exclusion and marginalisation of homeless people – support them to find information relating to their whakapapa (Dowdell & Liew 2019)

Key findings — Support into employment

Offer career related activities for users looking for work. Includes supporting individuals to submit job applications, facilitating educational workshops (US, OCLC, 2010)

Key findings — Leisure

Opportunities for leisure

Opportunities to participate in a range of leisure and entertainment activities (OCLC, 2010)

During COVID-19 pandemic access to online materials, eBooks, online platforms for purpose of education and entertainment (Garner et al., 2021)

Key findings — Having a voice

Opportunities to participate in community related issues such as local politics – to express one's views (Byrne, 2018)

Key findings — Equity of access

Access to information and tools

Access to digital world, both in terms of equipment and skill development (ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016; Reid & Bloice, 2021; Digital Inclusion Research Group, 2017)

Provides access to digital world in remote communities, includes development of skills, motivation and trust (Bell, 2020)

Improves individuals' level of use and confidence in accessing digital world (ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016)

School and kura libraries

Note, there are no specific findings in relation to kura and libraries, including exploring what a library means from a Te Ao Māori perspective. This is an area that needs to be explored.

Key findings — Student learning and achievement

Literacy and learning

Improved literacy development and engagement (Coker, 2015; Clark & Teravainen-Goff, 2018; Hughes, 2014)

Gaining confidence, creativity and agency as learners (Hughes et al., 2019, p.135)

Student achievement_

Improved test scores (Coker, 2015; Hughes, 2014; Lance & Kachel, 2018)

Enjoyment of reading linked with student achievement (PISA, OECD, 2010 as cited in Hughes, 2014)

Key findings — Student value of libraries

Access to resources

Help academically, support development of good researching skills (Todd 2012, Todd and Kuhlthau 2005a; both as cited in Johnston & Green, 2018)

Provides access to books they're interested in (Clark & Teravainen-Goff, 2018)

Reading for pleasure

Enjoy reading and writing more than other students; also see themselves as better readers and writers (Clark & Teravainen-Goff, 2018)

Key findings — Improved sense of wellbeing

Safe space

Experiencing the library as safe, accessible, welcoming, a third space (Raffaele, 2021)

Social cohesion

Feeling included (Buchanan, 2012; Weeks & Barlow, 2017, both as cited in Hughes et al., 2019)

Finding the library conducive for recharging, relaxing and to interact socially (Merga, 2021)

Increased feeling of belonging (Raffaele, 2021)

Personal development

Feeling better about oneself, more confidence, resilience, self-esteem (Teravainen & Clark, 2017, p.24, as cited in Hughes et al., 2019)

Digital citizenship

Knowing how to be a good digital citizen (Hughes et al., 2019)

Key findings — Health

Health information_

Access to health information, incl. self-help (Lukenbill & Immroth, 2009, p.3, as cited in Merga, 2020)

Tertiary libraries

There was limited evidence in the selected literature of the contribution tertiary libraries make to social and cultural benefits. This could be a gap in the research.

Key findings — Study outcomes

Student achievement

Improved student success (Oliveria, 2018; Seale & Mirza, 2020; Connaway et al., 2017)

Improved career prospects (Oliveria, 2018; Seale & Mirza, 2020; Connaway et al., 2017)

Indication that greater library use is positively associated with Grade Point Averages (Allison, 2015; Soria et al. 2017)

Conversely, a lack of access for sole parents in a polytechnic created a range of learning barriers which had a negative impact on students' learning experiences (Barnes, 2016)

Student retention_

Improved student retention (Oliveria, 2018)

Seen as crucial for many 'first timers' in tertiary education (polytechnic library) (LIANZA, 2017)

Key findings — Support teaching and learning

Embedded librarian

Embedded librarian increases satisfaction with library services and helps significantly with online assignments (Edwards et al., 2010)

Mātauranga Māori

Successful application of Ngā Kete Kōrero and Ngā Upoko Tukutuku – transformed library users experience of accessing material, and enhancing te reo Māori access and facilitated retrieval (Bardenheier et al., 2015)

Key findings — Student wellbeing

General wellbeing

Digital wellness initiatives (Feerrar, 2020)

Place to study away from other distractions (Hinder, 2011)

Collegial, inclusive space

Improved wellbeing – collegiate experience (Oliveria, 2018; Seale & Mirza, 2020; Connaway et al., 2017)

Mutual student support (Hinder, 2011)

Acted as a cultural centre where students meet, study and work with others from the same community (Hinder, 2011)

Key findings — Skill development

Improved data, information and digital skills

Improved skills such as improved data literacy, data management (Corrall, 2014)

Improved digital skills including how to maintain digital wellness and effectively navigate the online environment (Feerar, 2020)

Development of good digital and information literacy skills (Martzoukou, 2020)

Helped students access and use online resources, including finding information from credible and reliable sources (Martzoukou, 2020)

Key findings — Lecturers – teaching and research

Research support

Support with research (Oliveria, 2018; Seale & Mirza, 2020; Connaway et al., 2017).

Help with research into COVID-19 through information curated by the library for this purpose (Martzoukou, 2020)

Improved teaching

Improved teaching (Oliveria, 2018; Seale & Mirza, 2020; Connaway et al., 2017)

Heritage libraries

There was limited evidence in the selected literature in relation to the benefits of heritage libraries. 4

Key findings — Equity of access

Access to material not readily available elsewhere (Traue, 2010; National Library, 2012b)

Key findings — Cultural connection

Cultural preservation_

Access to cultural assets (Field & Tran, 2018; Loach et al., 2017)

Impact for whānau, hapū, iwi reconnecting with their taonga, mātauranga Māori, and te reo. (interview evidence)

Special libraries

There was limited evidence in the selected literature of the contribution special libraries make to social and cultural benefits. This could be a gap in the research.

Key findings — Health

Access to health information_

Provision of wide range of information and digital services – important clinically and financially (Peterson et al., 2015)

During COVID-19 provided clinicians and decision-makers with much needed information about the pandemic, including addressing issues with misinformation and information overload (CHLA, 2021)

Bridging inequities through the provision of information for health professionals who serve underserved and vulnerable populations (CHLA, 2021)

Improved practice

Time saver for clinicians (CHLA, 2021)

Providing clinicians with information which leads to improved patient outcomes (Canadian Health Libraries Association (CHLA), 2021)

Key findings — Research

Collaborative environment

Collegial space – open dialogue and exploration of ideas (Kennedy, 2018)

Access to resources

Support with research – helps generate findings (Kennedy, 2018)

Researchers helped to develop their understanding of the pandemic by the libraries curating resources relating to COVID-19 (Martzoukou 2020)

Host organisation perspective

The Framework sets out the following question to consider in relation to host organisations:

How are libraries supporting the priorities and needs of their communities and hapū?

The information below set out the findings from the selected literature from the perspective of host organisation for each library sub-sector (i.e. public, school, tertiary, heritage, special). There is a need for further research in Aotearoa that explores the role of libraries in supporting their host organisation to meet its Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations and ensure equity of access for hapū, iwi and other marginalised groups.

Due to the amount of research findings, this section is organised by sub-sector.

Public libraries

The Local Government Act 2002 sets out the purpose of local government which includes promoting the social, economic, environmental, and cultural wellbeing of communities, today and in the future.5 This is an area that would benefit from Aotearoa based research and the use of centralised data, such as the work PLNZ has been carrying out.

Note, in the selected literature there were no references to the contribution libraries make to the environment; this is a suggested area for further research in A Tool to Support Measuring Libraries Impact.

Wellbeing findings — General

Equity of access

Equity of access for vulnerable populations and diverse needs (Cole & Stenström, 2021; ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016)

Help address inequities – improved access to digital resources, including free access, improved skills, improved confidence, greater levels of participation (ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016; Digital Inclusion Research Group, 2017)

During COVID-19 providing ongoing access to digital services which supported access to library services (Garner et al. 2021)

During COVID-19 pandemic – support access to education, social and health information; support community initiatives to connect with community members, distributed emergency food supplies, supporting community resilience (Reid & Bloice, 2021; Cowell, 2020, as cited in Rosenfeldt & Cowell 2021)

Lifelong learning and education

Contribution to literacy, lifelong learning and wellbeing of communities (PLNZ, n.d.)

Provide education and learning services designed to meet specific needs of disadvantaged and/or vulnerable groups (Cole & Stenström, 2021; ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016)

Civic engagement

In local authorities – provides a vehicle for engaging with the community – supports opportunities for citizens to actively participate in local politics (Stilwell, 2009)

Wellbeing findings — Environment

in the selected literature there were no references to the contribution libraries make to the environment; this is a suggested area for further research in A Tool to Support Measuring Libraries Impact.

Wellbeing findings — Social

Community connection and inclusion

Improved social cohesion through reaching underrepresented populations (Sørensen, 2021)

Providing access to diverse cultural material (Sørensen, 2021)

Acting as a multicultural bridge which supports integration into a new environment (Lim & Boamah, 2019)

Support improved social cohesion (Public Libraries Victoria Network et al., 2011)

Facilitate community interaction (Field & Tran, 2018)

Promote participation, communication and empowerment (Audunson et al., 2019)

Reduce marginalisation of homeless people (Dowdell & Liew, 2019)

Recreation

Enjoy recreational activities (ALIA et al. and I & J Management Services, 2016)

Support in social engagement and use of leisure time during COVID-19 pandemic (Goddard 2020, p.3)

Wellbeing findings — Economic

Financial gain

Evidence indicates public libraries generate returns between 3:1 to 5:1 on investment (LIANZA, 2014).

Most recent calculation for Aotearoa was in 2002 which indicated a ROI of $3.50 (Mc Dermott Miller, 2002 as cited in ALIA et al. & I&J Management Services, 2016)

Stimuli through library's own expenditure (capital and operating costs) plus library customer spending (Public Libraries Victoria Network, 2011)

Moving people over to online channels for services creates cost savings (Wagg & Tinder Foundation, 2016)

Non-commercial

Provides access to resources and leisure activities to economically impacted people and disadvantaged groups (OCLC, 2010)

Help drive equitable and inclusive economic growth through understanding the diverse needs of their community (Field & Tran, 2018)

Employment support

Provide career related activities to support individuals seeking employment (OCLC, 2010)

Wellbeing findings — Cultural

Cultural value

Create opportunities for people to reconnect with their cultural roots – whakapapa (Dowdell & Liew, 2019)

Overcoming cultural gaps by providing access to diverse cultural material (Sørensen, 2021)

Supporting immigrants to Aotearoa adapt to a different sociocultural system (Lim & Boamah, 2019)

School and kura libraries

There are some general limitations that should be noted in relation to the literature and school and kura libraries, including:

indications are that school libraries are under-utilised in delivering the curriculum (Emerson et al., 2018), as such there are opportunities for schools to have greater impact on both teaching and learning (LIANZA, 2020)

care needs to be taken when considering the findings from other countries due to differences between the operating context of Aotearoa and overseas. This includes school principals and the Board of Trustees determine the budget for a school library, including whether a library exists. Other differences that could impact on the findings from international research include in some schools library books are spread through the classrooms and differences in the skills of library staff (LIANZA, 2018; Softlink, 2019; National Library NZ, 2009).

There is an opportunity for research to be carried out that examines the contribution school and kura libraries make in relation to Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations, and in supporting equitable access to education. This includes considering how 'libraries' is defined.

Key findings — School reputation/outcomes

Learning and literacy development

Contributes to literacy development, learning and wellbeing (LIANZA et al., 2018)

Can contribute to digital literacy, considered an extension of supporting literacy (Johnston & Green, 2018))

Improved student achievement, e.g., improved reading scores (Coker, 2015; Hughes, 2014; Lance & Kachel, 2018; Clark & Teravainen-Goff, 2018)

Improved educational outcomes, including literacy, digital literacy (Softlink, 2019; Softlink, 2020)

Contribution to curriculum

Meeting the requirements of the curriculum (essential to long-term education strategies (IFLA School Library Manifesto, 2021)

Key findings — Equitable learning outcomes

Equitable access to resources

Provides access to reading, see as particularly important for literacy development for students from lower socio-economic background (Krashen, 2004, as cited in Hughes, 2014)

Qualified librarian increases benefits Lance & Schwarz, 2012 as cited in Lance & Kachel, 2018)

Supports achievement and motivation for students with disabilities (Small & Snyder, 2009, Small et al., 2009, Small et al., 2010; all as cited in Johnston & Green, 2018)

Potentially a causal link between supporting development of digital literacy and student outcomes (Adams Becker et al., 2017, as cited in Mardis et al., 2018)

Key findings — Promote student wellbeing

Sense of belonging

Contributes to an improved sense of belonging and wellbeing in students (Raffaele, 2021)

Cultivate a sense of belonging and sanctuary, reading opportunities that support wellbeing (LIANZA et al., 2018; Merga, 2021)

Can create a welcoming space, supports belonging to the school community (Raffaele, 2021)

Safe, trusted space

Safe space (Douglas & Wilkinson, 2010, as cited in Clark & Teravainen-Goff, 2018)

Provides a third space for students, includes accessible, safe, free from charge, welcoming to all, interactive and collaborative (Raffaele, 2021)

Improved mental health

Improved mental health (Clark & Teravainen-Goff, 2018)

Improved student wellbeing, including mental health, sense of belonging (Merga, 2020; Raffaele, 2021)

Conducive to recharging, relaxing and interactive social activities (Merga, 2021)

Key findings — Personal development

General personal development

Support development of "feelings of success and accomplishment, resilience, developing positive self-concept, self-esteem" and independence (Teravainen & Clark, 2017, p.24, as cited in Hughes et al., 2019)

Can be inclusive hubs, support social learning and personal development (Buchanan, 2012; Weeks & Barlow, 2017, both as cited in Hughes et al., 2019)

Digital citizenship

Online environments - coaching students in responsible, critical learning practices and digital citizenship (Hughes et al., 2019)6

Support development of digital literacy including good digital citizenship (LIANZA et al., 2018)7

Key findings — Health

Access to health information

"health information gatekeepers", supporting students to access relevant self-help material (Lukenbill & Immroth, 2009, p.3, as cited in Merga, 2020)

Tertiary libraries

The information below sets out findings from the selected literature for tertiary libraries. There is an opportunity for research to be carried out that examines the contribution tertiary libraries make to their institution meeting its Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations, and in supporting equitable access to education,

Key findings — Institutional reputation

Resource repository

Number of titles represented in a collection (Missingham, 2021)

Impact of research undertaken by university staff could be strengthened through open access in Aotearoa (Fraser et al., 2019)

Teaching and research support

Collaborating with lecturers to improve teaching, and support research (Oliveria, 2018; Seale & Mirza, 2020; Connaway et al., 2017)

Mātauranga Māori

Successful application of indigenous frameworks, that is Ngā Kete Kōrero and Ngā Upoko Tukutuku (Bardenheier et al., 2015)

Key findings — Economic return

Calculated Return On Investment (ROI) is between 2.9:1 and 5.4:1. ROI in Aotearoa has not been calculated (LIANZA, 2014)

Key findings — Improved student outcomes

Learning and achievement

Supporting student learning and success (Oliveria, 2018; Seale & Mirza, 2020; Connaway et al., 2017)

Helps students achieve academically (Oliveira, 2018)

Academic outcomes improve alongside use of books and web-based services (Soria et al., 2017)

In Aotearoa seen as crucial for many 'first timers' in tertiary education (LIANZA, 2017)

Retention

library user associated with improved student retention in 1st year (Murray et al., 2016)

Dedicated space

Space for students to mutually support each other's studies (Hinder, 2011)

Provides study space away from other distractions (Hinder, 2011)

Digital safety

Improved digital "wellness" amongst students – such as reduced digital stress, how to navigate online personal health, conduct healthy relationships online, balancing digital interactions (Feerar, 2020)

Key findings — Information source

Access to reliable information_

For both students and academic staff libraries seen as information source. Students consider library search engines as more trustworthy and accurate (OCLC, 2010)

Used as an information centre by Pacific students (polytechnic in Aotearoa) (Hinder, 2011)

Curating information to help researchers develop their understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic (Martzoukou, 2020)

Key findings — Cultural centre

Used as a culture centre to meet, study and work with students from their own ethnic community, including providing mutual support (Hinder 2011)

Key findings — Improved skills

Digital tools and resources

Development of digital literacy frameworks and programmes for both students and university staff (Johnston, 2020)

Supported universities to use online resource (pre-pandemic) so only moderate growth during the pandemic

Information critique skills

COVID-19 created an opportunity to highlight the importance of critiquing information (WHO 2020, cited in Martzoukou 2020)

Key findings — Ethical service

Responsible information stewardship

Opportunity in Aotearoa for libraries to leverage their research support further – to use their positions of trust in an academic, culturally and ethically responsible way (Howie and Kara, 2019)

Value almost solely considered in economic terms, but tertiary libraries undertake important work that is oriented towards service, care and maintenance (Seale and Mirza, 2020)

Heritage libraries

A general limitation in relation to the literature is that in Aotearoa there are some specific issues relating to Mātauranga Māori, preservation of Te Reo Māori and taonga that need to be explored through research using Kaupapa Māori approaches.

Key findings — Reputation/prestige

Resource repository

Quality of collection – building and preserving ... comprehensive collection; material not readily available elsewhere (Traue, 2010; National Library, 2012b)

Public value

Contribution to public good (Eichinger & Prager, 2021)

Key findings — Economic value

The value of heritage collections is in materials they hold that cannot be easily accessed or found elsewhere (Traue 2010)

Key findings — Organisational role/strategy

Cultural preservation and sustainability

Strengths of the collection [Turnbull Library] include te reo, Māori life and history, settlement and ongoing development of Aotearoa (Traue, 2010)

Contributing to cultural sustainability presumably part of role/strategy of the host organisation (Field & Tran, 2018; Loach et al., 2017)

Collecting, managing and curating culturally historic material (Eichinger & Prager, 2021)

Host organisation aim

Contribution to Library Strategy (e.g. National Library Strategy – Te Huri Mōhiotanga Hei Uara – Ngā Tohutohu Rautaki Ki 2030)

Special libraries

Key findings — General

Information skills

Saving time in information searches and retrieval, greater success in research, providing better knowledge on how to find information (LIANZA, 2014)

Financial gain

ROI calculated at $5.43:1 (LIANZA & Thomas, 2016)

Knowledge development

Intrinsic value – contribution to knowledge generation (CHLA, 2021; Kennedy, 2018; Martzoukou, 2020)

Key findings — Health

Evidence-based practice and quality care

Provides clinicians with access to evidence which supports improved patient outcomes (Canadian Health Libraries Association (CHLA), 2021; Peterson et al., 2015)

Supports organisational performance – both in quality of care and efficiencies by providing clinicians and decision-makers with much needed information during the COVID-19 pandemic, includes addressing misinformation and information over-load issues (CHLA, 2021).

Reputational benefits with better health outcomes and improved quality of decision-making, patient management and treatment (Peterson et al., 2015)

Financial gain

Estimated ROI in Australia is 9:1 (LIANZA, 2014)

Contribution to operational efficiencies, e.g., saving health professionals time as library staff can extract information faster) (interview evidence)

Key findings — Parliament

Contribution to democracy

Disseminates research which supports decision-making in democracies (Al Baghal, 2019; Hernández & González, 2018)

Financial and social value

Provide positive social ROI – in US market was calculated as 5.7:1; and contingent valuation as 0.51 in benefits (Hernández and González, 2018)

Key findings — Government

Information to support Government

Provision of information that aligns well with business needs of agency and supports policy development (Hallam, 2017)

Key findings — Research

Safe, collegial space

Opportunity to provide safe, collegial spaces for discussion, support collaboration (Kennedy, 2018)

Knowledge development

Generation of new ideas (Kennedy, 2018)

Contribute to the mission and strategic objectives of their stakeholders (Kennedy, 2018)

Key findings — Corporate

Supporting business

Contribute to almost any aspect of business performance (LIANZA, 2014)

Communities, hapū and iwi perspective

The Framework sets out following question to consider in relation to communities, hapū and iwi. 8

How are libraries supporting the priorities and needs of their communities, including hapū and iwi?

The information below sets out the findings from the selected literature from the perspective of communities, hapū and iwi. Note, in the selected literature there were no references to the contribution school and kura libraries make to their broader communities. This does not mean that school and kura libraries do not benefit these communities, rather it indicates that it is a current gap in the research which needs to be addressed.

Like the other two perspectives, there is a need for research in Aotearoa that explores how tangata whenua and other groups define what is a library, how the libraries obligations to meet Te Tiriti o Waitangi is being met, and ensuring that the different communities the library serves experience equity of access. This would help libraries understand and articulate to what extent, if at all, they are meeting the needs of their communities, hapū and iwi.

Key findings — Public

Equitable, free access

Helping address inequities at a community level (such as reaching underrepresented groups) (Sørensen, 2021)

Improve equity of access (Cole & Stenström, 2021; ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016)

Help address societal inequities (access to free services) (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Promote democratic principles through providing free access to knowledge and information (Stilwell, 2009)

Digital inclusion

Public libraries provide free access to technology (OCLC, 2010)

Provision of digital services (access and skills) has helped libraries reach people who wouldn't normally use them (Wagg & Tinder Foundation, 2016)

Helps address digital inclusion for those with limited resources and/or minimal experience (ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016; Reid & Bloice, 2021; Digital Inclusion Research Group, 2017)

During COVID-19 pandemic libraries continued to provide support for ongoing digital access. There was increased use of online books, attending online events and engagement with online platforms [leisure and access to information activities] (Goddard, 2020; Reid and Bloice 2021)

Te Reo Māori

Opportunity to demonstrate how te reo Māori can improve and contextualise cultural experiences and understanding – has a role in wider revitalisation of te reo Māori (Lilley, 2019)

Information and digital literacy development

Public libraries contribute to literacy and knowledge development in their communities (Cole & Stenström, 2021; Gilpin et al., 2021)

Contribute to building of digital literacy including confidence (ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016; Reid & Bloice, 2021)

Community cohesion and resilience

Enabling connections to community agencies (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Existence of public libraries as a safe, free physical space – seen as an intrinsic value with public libraries unique ability to support crisis response and resilience (Stenström et al., 2019)

During COVID-19 research showed public libraries are places to connect and socially engage (Garner et al. 2021)

Tailor services to meet the diverse needs of the community, including education, learning services (Cole & Stenström, 2021; ALIA et al. & I & J Management Services, 2016)

Referred to as the 'new town square' – create opportunities to discuss community issues. Also, to learn about events, socialise, celebrate creativity, cultural identity and enjoy recreational activities (ALIA et al. and I & J Management Services, 2016)

During COVID-19 pandemic - strength of public libraries was their understanding of their local communities, including a personalised approach in responding to community needs, helping support community resilience (Reid & Bloice, 2021)

During COVID-19 pandemic – contacting library members, supporting access to emergency food services, health and wellbeing information, raising awareness of library services (Cowell, 2020, as cited in Rosenfeldt & Cowell, 2021)

Social and cultural value

Support community health, school effectiveness, and cultural interaction. Includes being part of a broad network of support, such as community groups

Support people to flourish through services provided, social interaction in their spaces, their community networks (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2021)

Support social change and inclusion, create cultural and social space (Corble, 2019; Audunson et al., 2019)

Contribute to community cohesion and development (Public Libraries Victoria Network et al., 2011)

Opportunities to participate in cultural activities (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Civic engagement

Actively promote this role through providing resources relating to law, government, and public policy as well as literacy and civic understanding programmes (Byrne, 2018)

Support participation in local politics – safe and trusted space which helps foster freedom of expression and supports citizens to actively participate in the political life of their community (Stilwell, 2009)

Key findings — School

See note above, no evidence relating to school libraries contribution to their broader community was found in the selected literature.

Key findings — Tertiary

Sharing skills and practice

Using their relationships to support skill development and sharing of best practice between different institutions, includes enhancing digital services, improving data literacy and data management (Corrall, 2014)

Key findings — Heritage

Cultural preservation

Provide access to materials that enable hapū and iwi to reconnect with their taonga (interview); also inferred in National Library, 2021

Key findings — Health

Improving equity

Helps bridge inequities through the provision of information (CHLA 2021)

Aotearoa – society perspective

The Framework sets out following questions to consider in relation to Aotearoa society:

How do library services provide public goods for Aotearoa?

What does Aotearoa require from library services that benefit people living here, both today and tomorrow?

The Treasury's Living Standards Framework was used to develop impact areas/themes at an Aotearoa level. The Living Standards Framework 2021 9 sets out the following aspects of our lives (both individual and collective) that are important for our wellbeing:

Environment

Knowledge and skills

Leisure and play

Subjective wellbeing

Health

Cultural capability and belonging

Work, care and volunteering

Family and friends

Engagement and voice

Safety

Income, consumption and wealth

Housing

The information below sets out the findings from the selected literature within each of the aspects of wellbeing. Note, in the selected literature there were no references to the contribution libraries make to the environment, housing, and subjective wellbeing. That is not to suggest that libraries do not contribute to these areas, rather that they do not appear to have been explored and/or it was difficult to deduce libraries' contribution.

Wellbeing findings — Health

General health and wellbeing

Contribute to improved health (Sanderson 2020)

Schools and tertiary libraries support improved student wellbeing

Public libraries usage brings significant wellbeing benefits (Garner et al, 2021)

Public libraries during COVID-19 contributed to improved wellbeing for vulnerable library members – this included calling them, supporting access to emergency food services, health and wellbeing (Australia, Cowell, 2020, as cited in Rosenfeldt & Cowell, 2021)

Social capital and inclusion

Public libraries support building social capital and inclusion (Audunson et al., 2019 ) (through promoting participation, communication and empowerment)

Public libraries – seen as a 'lifeline' – facilitating community interaction (Field & Tran, 2018)

Mental health

School libraries contribute to improved mental health [in school students] (Merga, 2020; Raffaele, 2021)

Public health

Tertiary (university) libraries supported researchers to develop a better understanding of the Covid-19 pandemic

Health libraries contribute to better health outcomes at a population level (deduced) (Canadian Health Libraries Association (CHLA), 2021)

Health, Tertiary and Research libraries have contributed to understanding the COVID-19 pandemic to support public health decisions (Martzoukou 2020, CHLA 2021)

Wellbeing findings — Knowledge and skills

Access to curated knowledge_

Public libraries provide access to books, information, resources which contribute to learning

Public libraries experienced increased engagement with their online platforms during the COVID. Considered to show "tremendous value when it comes to education ..." (Goddard, 2020, p.3)

Libraries provide education support (Sanderson 2020)

Access to information and enhancing education (Barclay, 2017)

Tertiary libraries contribute to UN SDGs – promotion of literacy and skills, bridging gaps in information access, communicating knowledge, supporting research and academic community, improving access to digital collections (Missingham, 2021)

National Library – helping preserve and promote a nation's heritage (Field & Tran, 2018)

LIANZA (2014, p.3) – core mission of libraries is supporting a society of "literate, knowledgeable ... "

Equity of access to tools which support development of knowledge and skills (i.e. digital technology)

supporting citizens to navigate an information environment filled with 'fake news' and 'weaponised narratives' Rainie (2018)

Information and digital literacy

School libraries support development of literacy, digital literacy and digital citizenship, developing information literacy, curriculum related-learning (Softlink, 2019; Softlink, 2020)

Essential to long-term education strategies, including "literacies, information provision and creation, and economic, social and cultural development" (School Library Manifesto, 2021, p.21)

Libraries contribute to addressing digital inclusion challenges, including access to technology and development of digital literacy skills (Barclay, 2017; Digital Inclusion Research Group, 2017; Wagg & Tinder Foundation, 2016)

Knowledge development

Public, school and tertiary libraries – support development of literacy; also knowledge generation through helping users find information they need, also support development of research skills. Extent of contribution in Aotearoa is unclear due to resource constraints – while some larger libraries may be able to achieve this type of outcome – it is not necessarily the case for less well-resourced libraries (interview evidence indicates some public and school libraries may not have any qualified librarians)

Special libraries such as research and heritage libraries contribute directly to the development of knowledge (heritage – collects and preserves material for use by researchers in the future) – builds a comprehensive collection of the country's national literature (incl. Mātauranga Māori, Te Reo, and taonga)

Research libraries contribute to knowledge generation

Wellbeing findings — Leisure and play

Opportunities for leisure and play

Public libraries create opportunities to socialise, express and celebrate creativity, enjoy recreational activities (ALIA et al. and I & J Management Services 2016)

Create opportunities to participate in leisure activities (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Social engagement

Result of COVID-19 pandemic is recognition by library workers and research participants that public libraries support social connection and engagement (Garner et al. 2021)

During the COVID-19 pandemic increased usage of online library services (e.g. eBooks and online platforms), supporting social engagement Includes holding online events (Reid and Bloice, 2021) – also highlights importance of digital inclusion initiatives (Reid and Bloice, 2021)10

Wellbeing findings — Cultural capability and belonging

Connection and belonging

Public libraries – mechanism for social change and inclusion through creating cultural and social spaces ((Corble, 2019)

Public libraries linked with community cohesion and development (Public Libraries Victoria Network et al., 2011)

Core mission of libraries is supporting a society of ... connected citizens LIANZA (2014, p.3)

Connecting with users from historically underrepresented communities (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2021)

Cultural participation and sustainability

Public libraries – express and celebrate cultural identity (ALIA et al. and I & J Management Services 2016)

Public libraries create opportunities to participate in cultural activities (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Cultural sustainability through acquiring and maintaining cultural assets (Field & Tran, 2018; Loach et al., 2017)

Heritage libraries - Collects, manages and curates cultural heritage – public good which should remain in public ownership including digitizing ((Eichinger & Prager, 2021)

Turnbull Library – strengths of the collection include te reo, Māori life and history, settlement, and ongoing development of Aotearoa (Traue, 2010)

Wellbeing findings — Work, care and volunteering

Employment support

Libraries are a core component of wider economic and employment infrastructure (Sanderson 2020)

Support job seeking and training (Sanderson 2020)

Wellbeing findings — Family and friends

Opportunities for socialising

Public libraries – opportunities to make new friends (interview evidence), socialise (ALIA et al. and I & J Management Services 2016)

Wellbeing findings — Engagement and voice

Access to reliable knowledge

Public libraries promote democratic principles through free access to knowledge and information (Stilwell 2009)

Public libraries provision of resources relating to law, government, public policy, programmes in civic understanding etc (Byrne, 2018)

Libraries are trusted to be accurate sources of knowledge (Rainie, 2018; Stilwell, 2018)

Civic engagement

Public libraries operate as 'new town square' – opportunities to discuss community issues, participate in community events, be aware of community news (ALIA et al. and I & J Management Services 2016)

Fosters freedom of expression and creates space for citizens to participate in political life of their community (Stilwell 2009)

Enable connections in community agencies (Monaghan, 2016; Sirkul & Dorner, 2016; Vårheim, 2014; all as cited in Cole & Stenström, 2021)

Wellbeing findings — Safety

Safe, trusted space

Physical, safe space - ability of public libraries to support crisis response and resilience highlights the value they deliver to the ... wider societal ecosystem (Stenström et al., 2019).

Libraries also support the development of ... trust through promoting participation, communication, and empowerment for all (Audunson et al., 2019).

Wellbeing findings — Income, consumption and wealth

Employment support

Contribution to employment (applying for work, upskilling etc) (OCLC 2010)

Recreation

Enjoy recreational activities (ALIA et al. and I & J Management Services 2016)

Non-commercial

Help bridge the economic divide (Field & Tran 2018)

Reduced spending for economically impacted Americans (i.e. free services) (OCLC 2010)

Bibliography

Aabø, S. (2009). Libraries and return on investment (ROI): A meta‐analysis.New Library World, 110(7/8), 311–324 .

Al Baghal, T. (2019). Usage and impact metrics for Parliamentary libraries.IFLA Journal, 45(2), 104–113.

Allison, D. (2015). Measuring the Academic Impact of Libraries. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(1), 29–40.

START HERE

Allman, K., Blank, G., & Wong, A. (2021). Libraries on the Front Lines of the Digital Divide: The Oxfordshire Digital Inclusion Project Report.

Anderson, M. (2012). An exploration of the ethical implications of the digitisation and dissemination of Mātauranga Māori. Masters Thesis, University of Waikato.

Audunson, R., Aabø, S., Blomgren, R., Evjen, S., Jochumsen, H., Larsen, H., Rasmussen, C. H., Vårheim, A., Johnston, J., & Koizumi, M. (2019). Public libraries as an infrastructure for a sustainable public sphere: A comprehensive review of research. Journal of Documentation, 75(4), 773–790.

Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA), Australian Public Library Alliance (APLA), National and State Libraries Australia (NSLA), & I & J Management Services. (2016). Guidelines, standards and outcome measures for Australian public libraries.

Deakin, ACT: Australian Library and Information Association.

Barclay, D. A. (2017). Space and the Social Worth of Public Libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 36(4), 267–273.

Bardenheier, P., Wilkinson, E. H., & Dale (Te Rarawa, Te Aupōuri), H. (n.d.). Ki te Tika te Hanga, Ka Pakari te Kete: With the Right Structure We Weave a Strong Basket. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 53(5–6).

Barnes, J. (2016). Student-Sole-Parents and the Academic Library. New Zealand Library & Information Management Journal, 56(1), 46–51.

Becker, S., Crandall, M. D., Fisher, K. E., Kinney, B., Landry, C., & Rocha, A. (2010). Opportunity for All: How the American Public Benefits from Internet Access at U.S. Libraries.

Bell, R. A. (2020). Mobile libraries and digital inclusion in non-urban Aotearoa New Zealand Victoria University of Wellington – Te Herenga Waka.

Blake, L., Balance, D., Davies, K., Gaines, J. K., Mears, K., Shipman, P., Connolly-Brown, M., & Burchfield, V. (2016). Patron perception and utilization of an embedded librarian program. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 104(3), 226–230.

Byrne, A. (2018). Democracy and libraries: Symbol or symbiosis? Library Management, 39(5), 284–294.

Canadian Health Libraries Association (CHLA). (n.d.). Statement on the Importance of Hospital Libraries.

Chawner, B., & Oliver, G. (2013). A survey of New Zealand academic reference librarians: Current and future skills and competencies. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 44(1), 29–39.

Clark, C., & Teravainen-Goff, A. (2018). School libraries: Why children and young people use them or not, their literacy engagement and mental wellbeing (p. 13). National Literacy Trust.

Coker, E. (2015). Certified Teacher-Librarians, Library Quality and Student Achievement in Washington State Public Schools (p. 71). Washington Library Media Association.

Cole, N., & Stenström, C. (2021). The Value of California's Public Libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 40(6), 481–503.

Connaway, L. S., Harvey, W., Kitzie, V., & Mikitish, S. (2017). Academic Library Impact: Improving Practice and Essential Areas to Research. American Library Association, 1–124.

Corble, A. R. (2019). The Death and Life of English Public Libraries: Infrastructural practices and value in a time of crisis [Doctoral, Goldsmiths, University of London].

Corrall, S. (2014). Library service capital: The case for measuring and managing intangible assets. In S. Faletar Tanacković & B. Bosančić (Eds.), Assessing Libraries and Library Users and Use: Proceedings of the 13__th International Conference Libraries in the Digital Age (LIDA), Zadar, 16-20 June 2014 (Vol. 13, pp. 21–32). University of Zadar, Department of Information Sciences, and University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Creaser, C. (2018). Assessing the impact of libraries – the role of ISO 16439. Information and Learning Science, 119(1/2), 87–93.

Digital Inclusion Research Group. (2017). Digital New Zealanders: The Pulse of our Nation (p. 105).

Dowdell, L., & Liew, C. L. (2019). More than a shelter: Public libraries and the information needs of people experiencing homelessness. Library & Information Science Research, 41(4), 100984.

Edwards, M., Kumar, S., & Ochoa, M. (2010). Assessing the Value of Embedded Librarians in an Online Graduate Educational Technology Course. Public Services Quarterly, 6(2–3), 271–291.

Eichinger, A. & Prager, K. (2021). We are needed more than ever: Cultural heritage, libraries and archives. In H. Werthner, E Prem, E.A. Lee, and C. Ghezzi (Eds). Perspectives on Digital Humanism (109-114).

Emerson, L., Kilpin, K., White, S., Greenhow, A., Macaskill, A., Feekery, A., Lamond, H., Doughty, C., & O'Connor, R. (2018). Under-recognised, underused, and undervalued: School libraries and librarians in New Zealand secondary school curriculum planning and delivery. Curriculum Matters, 14, 48–68.

Feerrar, J. (2020). Supporting digital wellness and wellbeing. ACRL Press.

Field, N., & Tran, R. (2018). Reinventing the public value of libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 37(2), 113–126 . [https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2017.1422174]

Fraser, M., White, R., Richardson, E., Hayes, L., Howie, J., White, B., Angelo, A., Broughton, S., & Fitchett, D. (2019). Open Access in New Zealand universities: An environmental scan. Report to CONZUL.

Fujiwara, D., Lawton, R., & Mourato, S. (2015). The health and wellbeing benefits of public libraries: Full report. Arts Council England.

Garner, J., Wakeling, S., Hider, P., Jamali, H. R., Kennan, M. A., Mansourian, Y., & Randell-Moon, J. (2021). Understanding Australian Public Library Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis: Report and Recommendations. Charles Sturt University (Libraries Research Group).

Gilpin, G., Karger, E., & Nencka, P. (2021). The Returns to Public Library Investment (Working Paper) (WP-2021-06). Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Goddard, J. (2020). Public Libraries Respond to the COVID-19 Pandemic, Creating a New Service Model. Information Technology and Libraries, 39(4), Article 4.

Hallam, G. (2017). Commonwealth Government Agency Libraries Review: Stage 2 Report, Consultation with senior executives and policy managers in government agencies. Australian Government Libraries Information Network (AGLIN).

Hayes, L. (2012). Kaupapa Māori in New Zealand Public Libraries Victoria University of Wellington - Te Herenga Waka.

Hernández, A., & González, L. A. (2018). Contribution to the Entailment Citizen: Estimate the Social Return on Investment of the Parliamentary Libraries. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries (QQML), 7(3), 489–499.

Hinder, A. T. (2011). Pacific Students and Their Perceptions of an Academic Library: A Case Study of Whitireia Community Polytechnic Victoria University of Wellington - Te Herenga Waka. [http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/1964]

Howie, J., & Kara, H. (2019). Research support in New Zealand university libraries. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 1–29.

Hughes, H. (2014). School libraries, teacher-librarians and student outcomes: Presenting and using the evidence. School Libraries Worldwide, 20(1), 29–50.

Hughes, H., Willis, J., & Bland, D. (2019). Students Reimagining School Libraries as Spaces of Learning and Wellbeing: Insights from research and practice. School Spaces for Student Wellbeing and Learning.

Imholz, S., & Arns, J. W. (2007). Worth Their Weight: An Assessment of the Evolving Field of Library Evaluation. Public Library Quarterly, 26(3–4), 31–48.

Institute of Museum and Library Services. (2021). Understanding the Social Wellbeing Impacts of the Nation's Libraries and Museums.

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). (n.d.). IFLA Internet Manifesto.

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). (2021). IFLA School Library Manifesto.

Johnston, M. P., & Green, L. S. (2018). Still Polishing the Diamond: School Library Research over the Last Decade. School Library Research, 21.

Johnston, N. (2020). The Shift towards Digital Literacy in Australian University Libraries: Developing a Digital Literacy Framework. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69(1), 93–101.

Kennedy, M. L. (2018). The Opportunity for Research Libraries in 2018 and Beyond. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 18(4), 629–637.

Lance, K. C., & Kachel, D. E. (2018). Why school librarians matter: What years of research tell us. https://kappanonline.org/lance-kachel-school-librarians-matter-years-research/

Lance, K. C., & Young, T. (2016). School Libraries Work! 2016: A Compendium of Research on the Effectiveness of School Libraries. Scholastic Library Publishing.

Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA). (2014). LIANZA Valuing of Libraries Report 2014.

Library and Information Association of New Zealand (LIANZA). (2017). Libraries in Aotearoa ITP Sector.

Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA), National Library of New Zealand, & School Library Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (SLANZA). (2018). School libraries and school library services in New Zealand Aotearoa.

Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA), National Library of New Zealand, & School Library Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (SLANZA). (2020). School libraries in Aotearoa New Zealand 2019.

Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA), & Thomas, L. (2016). Special Libraries Survey 2016. Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA).

Lilley, S. (2019). The role of libraries in Indigenous language revitalization: A te reo Māori perspective. Book 2.0, 9(1–2), 93–104.

Lilley, S., & Paringatai, T. P. (2014). Kia whai taki: Implementing Indigenous Knowledge in the Aotearoa New Zealand Library and Information Management Curriculum. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 45(2), 139–146.

Lin, W. X., & Boamah, E. (2019). Auckland libraries as a multicultural bridge in New Zealand: Perceptions of new immigrant library users. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 68(6/7), 581–600.

Loach, K., Rowley, J., & Griffiths, J. (2017). Cultural sustainability as a strategy for the survival of museums and libraries. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 23(2), 186–198.

Mardis, M. A., Kimmel, S. C., & Pasquini, L. A. (2018). Building of Causality: A Future for School Librarianship Research and Practice. STEMPS Faculty Publications, 52, 9.

Martzoukou, K. (2020). Academic libraries in COVID-19: A renewed mission for digital literacy. Library Management, 42(4/5), 266–276.

Matthews, J. R. (2019). What Is the Value of a Public Library? Possibilities, Challenges, Opportunities. Public Library Quarterly, 38(2), 121–123.

Medawar, K. (2021). Setting up a new library: Planning, challenges, and lessons learned. A case study about Qatar National Library. International Information & Library Review, 53(1), 84-96.

Merga, M. (2020). How Can School Libraries Support Student Wellbeing? Evidence and Implications for Further Research. Journal of Library Administration, 60(6), 660–673.

Merga, M. K. (2021). Libraries as Wellbeing Supportive Spaces in Contemporary Schools. Journal of Library Administration, 61(6), 659–675.

Missingham, R. (2021). A New Lens for Evaluation – Assessing Academic Libraries Using the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Journal of Library Administration, 61(3), 386–401.

Murray, A., Ireland, A., & Hackathorn, J. (2016). The Value of Academic Libraries: Library Services as a Predictor of Student Retention. College & Research Libraries, 77(5), 631–642.

Naccarella, L., & Horwood, J. (2020). Public libraries as health literate multi-purpose workspaces for improving health literacy. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 32(S1), 29–32.

National Library of New Zealand. (2009). School Libraries in New Zealand: Information Paper.

National Library of New Zealand (2021a). Aotearoa People's Network Kaharoa.

National Library of New Zealand (2021b) Alexander Turnbull Library Collections.

Oliveira, S. M. (2018). Retention Matters: Academic Libraries Leading the Way. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 24(1), 35–47.

Online Computer Library Center (OCLC). (2010). Perceptions of Libraries, 2010 Context and Community. A Report to the OCLC Membership. OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc.

Oxborrow, K. (2020). "It's not just a professional development thing": Non-Māori librarians in Aotearoa New Zealand making sense of mātauranga Māori. Victoria University of Wellington - Te Herenga Waka.

Pasquini, L. A., & Schultz-Jones, B. (2019). Causality of School Libraries and Student Success. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 8(3).

Peterson, M., Harris, L., & Siemensma, G. (2015). The Clinical and Economic Value of Health Libraries in Patient Care. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 10(2), 65–67.

Public Libraries of New Zealand (PLNZ). (n.d.). Public Libraries of New Zealand Strategic Framework 2020-2025.

Public Libraries Victoria Network, SGS Economics & Planning, & State Library of Victoria. (2011). Dollars, sense and public libraries: The landmark study of the socio-economic value of Victorian public libraries. State Library of Victoria.

Pugh, S. (2012). Value for money: Best practice options for demonstrating return on investment for libraries. ALIA 2012 Biennial Conference, Sydney, Australia.

Raffaele, D. (2021). Cultivating the 'Third Place' in school libraries to support student wellbeing.

Rainie, L. (2016). Americans, Libraries and Learning. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech.

Rainie, L. (2018, April 9). The Information Needs of Citizens: Where Libraries Fit In. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech.

Reid, P., & Bloice, L. (2021). Libraries in lockdown: Scottish public libraries and their role in community cohesion and resilience during lockdown.

Rosenfeldt, D., & Cowell, J. (2021). A place of knowledge and connection: Developing a health and wellbeing framework for public libraries. Research Outreach, 123.

Sanderson, L. J. (2020). Libraries in Times of Economic Downturn. Libraries Aotearoa.

Seale, M., & Mirza, R. (2020). The Coin of Love and Virtue: Academic Libraries and Value in a Global Pandemic. Canadian Journal of Academic Librarianship, 6, 1–30.

Simpson, S. (2015). Te Ara Tika Guiding Words: Ngā Ingoa Kaupapa Māori – Māori Subject Headings: Phase 3 research report. LIANZA, Te Ropū, and the National Library of New Zealand.

Softlink. (2019). The 2019 Softlink Australia, New Zealand and Asia-Pacific School Library Survey Report. Softlink. https://asla.org.au/research

Softlink. (2020). New Zealand School Library Survey Report 2020. Softlink.

Sørensen, K. (2021). Where's the value? The worth of public libraries: A systematic review of findings, methods and research gaps. Library and Information Science Research, 43(1).

Soria, K. M., Fransen, J., & Nackerud, S. (2017). Beyond Books: The Extended Academic Benefits of Library Use for First-Year College Students | Soria | College & Research Libraries. College & Research Libraries, 81(1).

Stenström, C., Cole, N., & Hanson, R. (2019). A review exploring the facets of the value of public libraries. Library Management, 40(6/7), 354–367.

Stilwell, C. (2018). Information as currency, democracy, and public libraries. Library Management, 39(5), 295–306 .

Traue, J.E. (2010). Designing a research library for optimal performance: A report on experience. Archifacts, Oct 2010, 79-98.

Wagg, S. & Tinder Foundation. (2016). [_Library Digital Inclusion Fund_]. (https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/insights/library-digital-inclusion-fund-final-report/)

Footnotes

The Framework is a tool designed to be used along with the DRE Strategy for the libraries sector. The DRE Strategy is a five-year Strategy to guide libraries in collecting, analysing and using data research and evidence to help them tell their story about the difference their library makes (See DRE Strategy Narrative). The libraries sector refers to all publicly funded libraries (public, school, tertiary, heritage, special libraries) and libraries which provide free access to resources, and/or benefit from public investment (e.g., law and private libraries)

This has not been estimated in Aotearoa

Research findings indicated that results are more significant when libraries are more salient to their local community

This was noted as a limitation in the review of selected literature

Research looked at qualified staff

Note, only about 50% of schools in Aotearoa teach and promote this

The definition of communities includes people living in one particular area or people who are considered as a unit because of their common interests, social group, or nationality. Such communities may be geographically dispersed, and/or use online platforms to engage with each other.

For more information about the Living Standards Framework 2021 see https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/tp/living-standards-framework-2021-html

There is a question about the applicability of these findings in Aotearoa given the largely different experience of the pandemic, except for Auckland. That is not to say that libraries did not play an important role.

Acknowledgements

The project team would like to thank Alex Thursby, Lewis Brown from the New Zealand Libraries Partnership Programme within the National Library who provided access to key documents, ongoing support and guidance. We would also like to thank Sue Sutherland, our Senior Expert Advisor, for her expert advice and insights.

In addition, we would like to thank NZLPP who funded this project.

June 2022

Download the High level summary of impact areas of libraries

Download the ‘High level of summary of impact areas of libraries’(pdf,945kb)