- Events

- Why make an atlas?

Why make an atlas?

Part of Connecting to collections 2023 series

Video | 1 hour

Event recorded on Tuesday 17 October 2023

Join Dr Chris McDowall at this ‘Connecting to collections’ talk for a thoughtful discussion about the creation and interpretation of maps. Chris will explore the fundamental question of ‘Why make an atlas?’ and reflect on the enduring significance of these geographical compilations.

Transcript — Why make an atlas?

Speakers

Joan McCracken, Dr Chris McDowall

Mihi and acknowledgments

Joan McCracken: Nau mai, haere mai, and a warm welcome to the October edition of Connecting to Collections Online. Ko Joan McCracken ahau, I'm with the Alexander Turnbull Library's Outreach Services Team. And I'm delighted you've joined us today.

This is a very special edition of Connecting to Collections. Our colleague, Igor Drecki, curator of the Cartographic Collection at the Alexander Turnbull Library was to give today's talk. Very sadly, Igor and his wife Iwona died in a car accident at the end of July.

I'm very grateful that our former National Library colleague and Igor's friend Dr. Chris McDowall is here today to acknowledge Igor and to share his own enthusiasm for maps.

As always, to open our talk today, we have as our Whakatauaki a verse from the National Library's waiata “Kōkiri, kōkiri, kōkiri” by our Waikato-Tainui colleague, Bella Tarawhiti.

Haere mai e te iwi

Kia piri tāua

Kia kite atu ai

Ngā kupu whakairi e.

[Welcome oh people

Let us work together

To search the collections

They are a wealth of knowledge.]

And now, a warm welcome to Chris McDowell. Let me tell you a little bit about Chris. Chris is a geographer and cartographer.

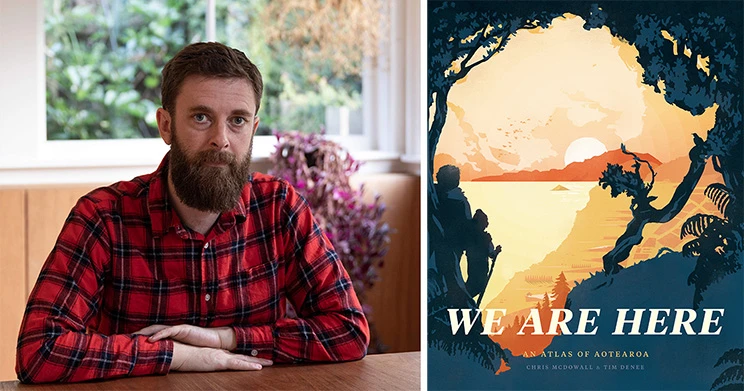

He has held positions at the University of Auckland, Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research and at the National Library of New Zealand. His current role at Te Whatu Ora in Tamaki Makaurau Auckland involves mapping communicable diseases and environmental risks. Chris is co-curator of the award-winning book, We Are Here: An Atlas of Aotearoa. Published by Massey University Press in 2019. And if you're hoping to get a copy, I'm sorry, it's out of print.

His maps and data visualizations have been exhibited at the National Library and Auckland War Memorial Museum and are featured widely in media. A very warm welcome, Chris.

Introduction

Dr Chris McDowall: Kia ora, thank you for the introduction, Joan. I'm just going to do one thing really quickly. And we'll just see how that goes.

Lovely. Yeah, so thank you very much, Joan. As Joan mentioned, my name is Chris. I trained as a geographer and have had this quite unusual career where I've worked as an environmental scientist, I've worked at the National Library of New Zealand in the Digital New Zealand project.

I've worked as a freelance cartographer. I've worked as a journalist. And most recently, for the last couple of years, I've been at Te Whatu Ora working in surveillance and intelligence.

So my current job, it involves data visualisation and mapping. But rather than the public, the audience is a collection of public health doctors, nurses, and the leadership. I've got a strong focus on communicable disease, things like measles, and tuberculosis, and pertussis, and enteric diseases, and environmental public health disasters, and a lot more.

But in a funny way, it reminds me a lot of working in the newsroom where you walk in and you think it's going to be a quiet day. And then there's a measles case gets confirmed or a demolition plant catches on fire and Māngere, or a sinkhole collapses in Parnell. And sewage starts spilling out into the Waitemata Harbour. And it's all on.

So I do a lot of work at the moment. The mahi is preparing for response during quiet moments. And then just very high-pressure quick turnaround work with limited information which sometimes involves people's lives.

And, today, I'm going to talk to you about the opposite of that. The opposite end of what I do, which is instead of this incredibly quick turnaround stuff, it's about the creation of something slow and methodical, something that will live in people's homes and in libraries for many years to come.

Tribute to Igor Drecki

But first, as Joan mentioned, I was not the original speaker for this session. It was supposed to be Igor Drecki, the curator of the Alexander Turnbull Library's Cartographic Collection and my friend for about 20 years.

And I'm just going to say a few words about Igor before the session proper. Igor and his wife Iwona lost their lives this winter in a car accident on the slopes of Ruapehu, the mountain which he loved I think more than any other.

This photo was taken in late August of 2022 at the GeoCart conference which was hosted at the National Library. Igor was the director of the conference, and perhaps, the most important figure in getting that conference going over the many years that it ran and for keeping it running. Although, certainly, a lot of other people were involved.

So this photo, I think, came from the end of the second day. Igor and I had not seen each other in some time and living in Wellington and myself and having moved back to Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland. But we spent most of our day together ahead of the conference before he got swept into his responsibilities as the organiser.

And I think that this photo does come from the end of that second day where Igor gave a retrospective of the cartography conference over the years. He went through all of these different attendees and presenters and highlighting some key presentations, acknowledging the contributions of different individuals, and even describing the career trajectories of some of the people who were there, including myself and others such as Tony Moore, who I think is also in the audience here today. Dr. Tony Moore from Otago.

Ahead of the talk, he confided in me that he was quite worried about the presentation. He had not prepared to the degree that he would like to. And he looked to me like he was tired.

And I suspect he stayed up very late the night before. But it was an amazing talk. It was so good.

And it really lifted people up. And I could see the way that the room responded to him. And I needed to leave the conference early to catch a flight. But I made sure that I would be able to be there for Igor's talk.

And at the very end, I was so moved by it. I pulled like a typical Chris McDowell move and just stood up and thanked him and all of the attendees and just thanked them for it. And that was the last time I ever saw Igor.

But the first time I ever saw him was in 1998. And it was so 25 years ago when I was a student at the University of Auckland. I spent a lot of time in the spatial analysis lab at the University.

And I'd hear people talk about this guy, Igor, who was really, really serious about maps. He'd submitted a master's thesis the year before and was staying on at the university to do a little bit more work as a postgraduate student.

We shared a supervisor. So the supervisor which Igor had when he was doing his master's in '96, '97, I then had when I was doing mine in '98 and '99. And there was a little bit of overlap between the work that I was doing and the work that Igor had done.

And so Professor Pip Forer suggested that I read Igor's thesis. And so that was the first way that actually ever engaged with Igor. It was not through conversation, but through his graduate thesis, his master's thesis, which was about the challenges of visualising different types of uncertainty.

And I've reread the thesis when I did my Ph.D. But I have not read it in nearly 20 years. And, unfortunately, it's not available online digitally. It's on deposit at the University of Auckland.

But I remember it as being a really, an excellent piece of work. And it's classic Igor. The thesis was a rigorous survey of all the different types of ways that uncertainty can creep into a cartographic project or product.

And then there was this equally rigorous survey of the different cartographic techniques that might be applied to describe different forms of uncertainty. So things like colour, or transparency, or animation. And the cartographers Jacques Bertin and Alan MacEachern loomed really large in that discussion. And I think it's fair to say they were two heroes of Igor's.

And then there was this methodical working through of all the different permutations every different combination of uncertainty and technique to establish their effectiveness and come up with a set of recommendations all through the lens of this quite rigorous analytical framework for assessing how effective something was. And it was this really, really solid thesis. It was so good, especially for a master's thesis.

And we finally met in person and, I guess, eventually became friends over a book about New Zealand Wine, something that neither of us are very interested in.

One of the supervisors for my master's was a rural geographer, Professor Warren Moran. And after my graduate studies, I worked on this manuscript with him that he was writing about New Zealand Wine. And I worked on the maps.

And I was really out of my depth. I'd never worked as a cartographer. I hadn't been trained in cartography.

And the maps I was making, they just weren't very good. But I learnt a lot. And during this time, I shared a room with Igor.

We sit together in the cartography lab and the University of Auckland's geography department or what at the time was the geography department. And I found him not intimidating, but quite unsettling at first. I didn't quite know how to read him.

And I couldn't work out whether he was being serious and when he was making a joke. But after a few months, we started getting along. And we built up a series of in-jokes and these conversational shorthands. And that evolved into a friendship.

And we reached a point where we talked really deeply about some things. Offering advice and support to the other at various times in our lives when we needed it.

And then I took a job in Palmerston North. And I left the New Zealand Wine project. And Igor took it over and did a much better job than I think I ever could have and saw it through and produced all of the maps of the different wine regions, and the climate, and the different graphs. And he did a really good job.

And then over the years, we stayed in touch. And although I'm a terrible correspondent — and will often go dark for many years. It's funny. There's a genuine, like a really genuine openness and warmth to me when I give a talk like this.

But in my private life, I am a bit of a hermit. And I think that that seeming contradiction wasn't always easy for Igor at times. During the creation of the atlas that I worked on ‘We are here’, I didn't show Igor any of the work for the years that I worked on it, except on two isolated occasions. When I showed him very, very small slices that I wanted to get feedback on from him.

A month before going to the printer, I printed everything off, and I took it up to the Auckland University Library where he was working at the time. And we spent six hours going through it without a break. We went through every single spread as it stood a month before printing.

And I don't think it ever occurred to either of us to pause. And the critique that he gave me was really deep and considered. At times, it was generous. At other times, it was just brutal. But it was always really honest and true.

Yeah, it's a really great privilege to receive that from him. And I really miss him. Yeah.

History of atlases in New Zealand

So for the rest of the time, I'm going to talk about why make an atlas. And I was trying to think of a talk that I could give that Igor would like, that would not be a talk that he gave, but would be a talk that he would respect. I think he would give quite a different talk to the same question.

And I'm not an expert on atlases. There are almost certainly people on this call who are much better versed than I am in them. And I say these things, though, more as a practitioner than as a scholar.

But the analytical frame that I'm going to bring to this. So, yeah, so this is the atlas that I made with Tim Denee. And as Joan said, sadly, it's not in print.

We actually had intended to do a second edition next year. But there are some delays in the census coming out that we had not quite expected. I think that they're good that they're getting everything right. So we hope to have a second edition in 2025, which will bring on that new census data.

But as I say, I'm not a scholar of atlases. But I sat down and just started thinking about the different ways in which, what an atlas is and the different sorts of ways that you might frame an atlas. And the ways that I think about an atlas is that an atlas is it's a curatorial act. It's a collection of a sort. And that decisions are made, difficult decisions often, about what should be included and what is not to be included.

An atlas is also an archive. Especially a print atlas. And it's actually thanks to Paul Diamond who is the person who helped me realise that in an early discussion that I was having about the challenges of making this atlas, that it's a thing that is bound and encapsulates, and that will persist and endure and marks a certain moment in time and set of circumstances.

And, of course, they're educational resources and they're reference materials and they're design objects. But there are two things that I wanted to use as a framing, in particular, or at least for the first part of this talk. The role of atlases as for nation-building and also in reckoning with the past.

And I think that we can see a real shift if we look back over the last 100-odd years of atlases in Aotearoa, New Zealand. And I argue that we have a couple of distinct phases. So for most of the 20th century, the atlases that were created had a lot to do with nation-building.

New Zealand was not alone in this, especially in the decades that followed World War II. There were many similar atlases created by Western nations. Those atlases, they rarely look back.

There's a big focus on population. But present patterns of population and demography on what's framed as natural resources and on infrastructure and industry. It's in a sense, it's an inventory — and the inventory is privileged over-explanation.

During the 1980s and the 1990s amidst social and economic restructuring that was happening here and around the world, but also a greater public discussion about colonialism and injustice, there was a rise of historical atlases that explicitly reckoned with the past. We see this happening in Australia, it happens in Canada, and the United States, and elsewhere.

For Aotearoa, the turn comes with the creation and the publication of the ‘Historical atlas of New Zealand’. So I'm going to run through a few different atlases and just talk about them in different aspects of them. These are not the only atlases from the 20th century or that first part, which would suggest where the atlas' has got this really explicit focus on nation-building.

But they're the ones that I happen to have. And I do think that they're really good examples of them. So, at left, we've got the ‘Descriptive atlas of New Zealand’ from 1959. We've got ‘New Zealand atlas’ from 1976.

And then, I actually won't be showing anything from it, but another New Zealand atlas this one from 1987, which is much more of a — it's in that black hole period, as I think of it, of atlases where it's really just — they're very good maps, but it's a just reference maps of different parts of New Zealand. There are no thematic or minimal thematic qualities to it.

So I'm going to be focusing first on these first two atlases and just looking at particular spreads. The very first one is actually the interior fold of the 1959 descriptive atlas of New Zealand. I'm just going to read a tiny bit of it.

So, “This publication presents New Zealand to the world. As the prime minister of New Zealand, the right Honorable Walter Nash MP has stated in the foreword. The atlas incorporates details of New Zealand's geography and geology with appropriate history and a good deal of our economy and sociology. It is, in a sense, an analysis and assessment of New Zealand's resources.”

So we're talking about an atlas here where the prime minister of the day writes the foreword or is credited as writing the foreword. And it's framed as a publication that presents New Zealand to the world.

Turning to the interior page, it's clear the very heavy government involvement in the atlas. We'll see this again with the New Zealand historical atlas. But there's a real difference, some real differences as well there, which we'll get to.

But the committees chaired by the surveyor general, the government printer, the DIA are there. We've also got a representative from the Alexander Turnbull Library, C. Taylor, who I'm sure that much more knowledgeable people than me on this call will know exactly who that is. And then representatives from the Department of Land and Surveys and the Department of Education. So this really is this government project.

And as we look through it, there are many of the spreads that one would expect to see in an atlas. They're present in pretty much every atlas which I'll mention, even with the exception of the New Zealand historical atlas which has got a different scope. But they're their in some of the later atlases that we'll look at, such as the ‘Contemporary atlas of New Zealand’.

And they're very good maps. They're really informative. And they're interesting, actually. And this is, I guess, I'm one of the things I'm getting at when I talk about how they're an archive, just to look at how subtly different some of the normal temperatures are compared to what we experience today.

Mapping population density

Here's a map of population. It's a map that I've kind of grown to respect more and more. I initially was not a fan of this map because I think it's a bit difficult to read. I still think that.

But I do respect the attempt to convey the distribution of population in quite a nuanced way. I think there's a little bit of a confusion and a bit of noise from between the subject, which is the population and the shaded relief that sits beneath it.

And initially, I didn't really like these 3D icons. But there's actually a real clarity to them in that you can — it's very clear to look at them and compare them to the key and see exactly what population size it is once you train your eye to it.

But there is something about the design that I think they could have worked on and just made it so it's a little less jarring and visually less noisy for the eye.

This is actually one of the few things which I showed Igor ahead of publication, just as a side note, in the very early days, was every atlas I've seen puts the North Island on the left-hand page and the South Island on the right-hand page. And we flipped that around.

So this is a very similar map that we put in ‘We are here’. Which instead of using proportional symbols, we put a dot, a very small little dot for every single household and business address in the country. And that's all that you see. And just from that alone, we built up a map of population.

But the thing that I showed Igor and sought his advice on was what if we put the South Island on the left and the North Island on the right. And the rationale being that then Auckland, and Christchurch, and Wellington could be almost in a dialogue with one another was the way that I expressed it to him. And I think he thought I was crazy.

He was like, it just doesn't matter. You can put them that way if you like. But these are not reasons that I understand what you're talking about. But I still stand by it. I actually think that it fits nicer on the page and that there's something about having our more sparse locales like the West Coast and Terawhiti on the margins rather than in the middle, that intuitively makes some sense to me.

And this idea of dots is something that runs through a lot of these atlases in order to represent people. This was another one. This is one that Igor did like very much, where we tried to show, we did this for different places around the country, where people work and live.

And I guess why I'm showing you this — and I think this is something that comes in some of these later atlases is that it's not actually in this text, it's in the text from the previous page, which shows the North Shore. But trying to show structure, as well as inventory of what exists or what's been recorded.

So here, the red dots represent where people work and the dark dots represent where people live. But we're also trying to show patterns of sparseness and density. So you can see somewhere like Remuera is very, very sparsely populated compared to parts of Counties Manukau, which is off-screen on the next page or parts of Henderson where there's this real mixing of workers and people living.

I'm really looking forward to recreating this map based on the last census to see how the patterns have shifted. And we'll probably emphasise some of that.

Returning to the 1959 atlas, though. I don't want to get too sidetracked with my own stuff. It's really I'm keen to just work through some of these maps.

Pre-European Māori population

This is really the only map that looks back. And it is a map that also appears in almost every atlas I've looked at where it's some attempt to represent the distribution of Māori population, pre-European.

And it's almost the only place where Māori appear in the entire atlas. There is one other section, which I've chosen not to show, which I should have actually probably shown it. Thinking it through. But it is about Māori in the modern day. But it's an extremely problematic spread.

Yeah. And I've held that back. There's a few things within this atlas which are the best that can be said of them are that they are products of the time. But they're certainly troubling aspects of a colonial agenda in the government of the day.

This is perhaps a little less. Yeah, less problematic, I think. And it is something that's been echoed throughout. Here, we've got a dot map which shows the approximation of the pre-European distribution of Māori around the country.

And this map as well has changed many times representing a change in popular understanding and scholarly and academic understanding of how widespread Māori were pre-European. This a very similar map as it appears in our atlas which is based just on the locations of Pa as recorded in the New Zealand Archeological Association database.

It doesn't include other forms of settlement. It is only fortified Pa. And, to me, it suggests a very rich incredibly dense patterns of habitation.

Atlas as inventory

This is also really typical of these earlier atlases where we look at land utilisation.

These spreads are where really think about the atlas as an inventory in order for the role of the atlas to promote a nation and show what a nation is. And so it's about how the land is used. So this is the 1959 ‘Descriptive atlas of New Zealand’.

And we see the use of land for extensive — for semi-extensive sheep farming. There's three different classifications for agriculture involving sheep and then dairying. And so there's four for sheep, orchards and market gardens. And then we've got what's called undeveloped land.

Skipping forward to the 1970s atlas, ‘New Zealand atlas’. It's almost identical different color scheme, but an almost identical legend. And just an update of the areas, the only thing that's really changed is the introduction of exotic forests with the rise of forestry. And plantation forestry that is. And also, the undeveloped land is now reframed as recreation and conservation or land that's not developed for farming.

This is the closest that we got to a map of — and it's not actually a map — a map of land utilisation. And it's not actually how the land is used so much as what covers the land.

And we made a deliberate choice not — to actually present it in a different way. And one of the things that I often do is try to think about how I want people to talk about the maps and what insights I'd like them to gain from looking at them. And so I think that a map like this is an excellent map as a reference map.

But it's quite a hard map in order to discuss unless you're reaching in and looking at a particular place. Because the irregular shapes of all of these different land uses are hard to compare. You can make statements about how say around Dargaville, there's semi-intensive like sheep and beef. But it's harder to make bigger statements about large patterns.

So what I tried to do was actually present a graph in the form of a map. I'm not sure how successful it is. And I know that this particular map graph gets misinterpreted occasionally.

But for the people who it works for, it does seem to really work. So if we look at the tip of the North Island, there's 1,000 — it's like saying that if you took all of the orchards and vineyards in the country, they'd occupy that 1,000-kilometer square stretch.

Similarly, if we took all of the urban and built-up areas that occupy an area the size of Rakiura of Stewart Island, that most of the North Island would be occupied by either low-producing grassland and high-producing grassland if it was all to be laid out in one place. I think that the text is quite good at conveying it. And watching people encounter this map, those who read the text do encounter do really take something away. But it can be a tricky one.

This is another example. This is from the 1970s New Zealand atlas which I think is perhaps — I remember from reading about the history of this atlas a long time ago that this was less well-received as some earlier atlases. And I can sort of see why in terms of some of the way in which it conveys information.

These pie graphs, for example, are — actually, I don't have too much about a well-used pie graph. But it requires a lot from the reader to interpret and to decipher and make sense of. And even once that's done, it's hard to be precise about any of the measures.

Everything is very vague. But the choice to put a map like this in I think is a really interesting one the curatorial decision to not just have this manufacturing map, but then a communications map, and an infrastructure map, and a whole lot of others when so much else is not represented. It really is still advancing a narrative of: this is this country, and these are the things that it has. Something that is looking to the future much more than the past.

And then all of these maps, all of these atlases have — in my opinion, these very effective, beautiful, useful, more descriptive maps as a series where you'll be able to look throughout the country and see different places.

Mapping earthquakes

I think this is the final one. I'm going to show from these older maps from the '50s and '70s. And this is actually just to draw a line. This is a direct inspiration for a map in the atlas that we created, which was a distinction between shallow earthquakes, those with a focal depth of less than 40 kilometres, and deep earthquakes, those that occur greater than 40 kilometres down.

And seeing this map, yeah, it was part of the way that we got to the way that we presented earthquakes within the book. Of course, we were not too far out from the devastating Darfield and then the Christchurch earthquakes in 2010s.

We took a slightly different approach. We actually lead with the deep earthquakes and then followed it up with the shallow earthquakes. With the deep earthquakes, these work a little better on the print than in the screen.

But trying to show the shape of the colliding continental shelves where the earthquakes are colored by depth and sized by magnitude. And so you can get a sense for, the sensitive reader at least, that the shelves are actually diving underneath one another. And then with the darker ones to the left of the page, to the west. And the lighter ones, to the east as the shelves slip down.

And then there's an unusual twist that occurs near the bottom of Fiordland where the reverse is happening. And then I guess this is a way if we look at the right-hand page and the pattern of shallow quakes.

This is one of the things which I sometimes when I think about an atlas as an archive is the way that — if you look at the shallow earthquakes in blue on the left-hand side here, just the complete absence of any shallow quakes in that Christchurch Canterbury plains area, there's a few around the Alps one around the coast. But there's nothing there. And that pattern continued for decades and decades until it didn't.

And an atlas is a glimpse into that. It is a glimpse into what was thought and known at a time. At least one consensus view of that. Whereas we, of course, know that there are these volatile faults that occur along those plains. And given the right conditions, they can have a really devastating result.

New Zealand historical atlas: visualising New Zealand

So after a period through the '80s. And so there are several atlases like that. And they all hit similar bases. They're different. But they're very much looking at: these are the things that exist and this is how we, with these forwards that are about presenting the nation to the world.

In the '80s, there's really not very much outside of maybe some school atlases and some reference atlases, such as that other New Zealand atlas that I showed from 1987 to show the cover of. But then we get to the ‘New Zealand historical atlas, visualising New Zealand’ from — which was published in 1997. And it's an extraordinary. It's a towering accomplishment.

Again, there's very heavy government involvement. But the composition of the committees and editorial teams who worked on it is really different. Perhaps, one of the most notable things is when compared to others that stands out is that there's a dedicated Māori committee who are advising and contributing to this atlas.

There's a cast of thousands beyond these really like giants of New Zealand academia. People like Jock Phillips as the chief historian. Sir Tipene O'Regan, Professor Evelyn Stokes. There's name after name after name through here.

Including in the acknowledgments, Joan McCracken is credited and many other Turnbull staff for their assistance in different aspects of supporting the archival research. And just looking at a few of these spreads, they're really remarkable.

It's one of the first things that I think of when I look at this atlas is it's trying to explain rather than just — it has a point of view. It's situated in time and space. It's looking backwards and forwards and trying to connect everything together.

And there's an emphasis on movement and there's an emphasis on change. On any given page, there is so much going on. So, for example, here, we're looking at Stone Resources, the discovery and use by Māori.

We've got Argillite Quarry sites in Northeast Nelson up there. We've got the distribution and movement of stone resources at different times in Māori history. There's a small case study of Aotea, Great Barrier Island showing both where there was obsidian and basalt sources on the island, but also where they were found in different parts of Aotearoa.

There's images of an island. There's silcrete deposits and sites in Otago. And then there's some images of the progression of how to make an adze or a specific type of adze. And it's just incredible.

This atlas keep me awake so many times at night looking at it. When we were working on ours — and I personally don't think it comes, our work comes close to this.

Here's another example from later. This is around colonial communication. It's challenging the reader in so many ways, this particular spread. It's looking at how changes and both the development of communications infrastructure, but also the changes in technology altered conceptions of time and space.

And it's also doing this through these quite unusual and challenging uses of cartographic projection. For example, the circular image to the map to the left, which is centered on Littleton and then distorts space according to time. It places Littleton at the center of a world and then shows how the various connections via different modes of transport.

Similarly, just the choice of what to include and how to title things and divide things into sections. So there's an entire section which has the title of the spread ‘From progress to uncertainty’. And so they look at the last — the contributors look at the last 30 years prior to the atlas being created.

And look at some of the changes that have occurred in terms of — in this spread, it's around demography, unemployment, economic change, and also social change and attitudes towards issues such as the future of South Westland's forests, opinions of the Springbok tour, opinions on homosexual law reform, and trying to show a nation that is wrestling with things and one that doesn't quite know where it's going, which is a real difference to some of those earlier atlases.

One thing that I do find tricky about the atlas is even as someone who spends all their time looking at maps and graphs, it is a hard read for me. There's so much going on. And I love that they have this at the start of the book.

There is a ‘How to use the New Zealand historical atlas‘ section where they teach the reader how to interpret the spreads in which it had come in the atlas, even showing down the bottom left there. Different ways that the eye might navigate through a plate. And that sometimes you're supposed to look like an S and sometimes you go round in a circle and other times.

As a design object, it's really intense. I do fear sometimes that there is a little bit too much packed in there. But, oh my goodness. It's unparalleled in terms of the amount of information and nuance.

And I can return to this over and over and over again and see something new. So there are little things in there, which I think are maybe even get in the way of the interpretation. For example, the railway track as a timeline.

I don't know how well that works. And I fear sometimes that it takes away rather than contributes. But then when I get past those little design obstacles, it's a knock-out, this thing.

Contemporary Atlas of New Zealand

Another atlas which is not quite so widely known and discussed came out two years later also from Bateman. This is the ‘Contemporary Atlas of New Zealand’. And I think it's a really important work.

It's by Russell Kirkpatrick who was one of the cartographers on the ‘Historical atlas’. And, again, it primarily focuses on the present but it does look back as well. And I think it even more heavily leans into challenging the reader by presenting things in unfamiliar ways.

There's a lot of unusual projection and maps which on first glance may not look familiar and need to be deciphered and interpreted. And in the act of doing that, draw you in, such as this dual spread of Polynesian settlement in the South Pacific and then the European exploration of the South Pacific, which are turned on their heads and looked at from the vantage of the islands rather than being flipped around on an angle with Antarctica just slightly off-page or off-map.

And in a way, that draws you in and makes you kind of question quite where you are. And I think in a way that actually enhances for myself, at least, my engagement with the material that's being presented and the ideas that are here.

Similarly, there's some really intense spreads. This one, for example, around migration is extraordinary in terms of how much information it packs in. But I do worry that sometimes it gets a little bit lost.

But when you're in it, it's really amazing. I mean, I think, there are seven or eight different visualisations here. Some of them layered on top of each other.

So top left, we've got an inter-regional migration showing the major net flows between regions of the country. Bottom left, we've got three different visualisations packed together. It's migration into Palmerston North where, again, it's one of these innovative projections where the globe is centered on Massey University campus.

And it's showing all of the different places that people are coming from. But it's also showing a bar graph, which is a breakdown of Palmerston North on census night 1991. And then also an age / sex structure of migrants to Palmerston North emphasising the large numbers of people in their 20s which makes sense for a university and research town.

And then top right, top right it's a lot. New Zealand arrivals with an Asian passport in 1991 to 1996 is the left-hand side. But then on the right-hand side of that same globe with the proportional circles is New Zealanders living in Asia on census night 1991 by region.

So it's like one is the people who are migrants coming into the country and moving places. And then on the right, it's like where people were living and where they've gone. And then finally, we've got internal migration between four major urban areas.

And so sometimes it's hard for me with maps like this or infographics really in a way like this to know quite what to take from each part. And so I think that individually each one of these has varying degrees of success. But together, I can't quite get there.

Microgeographies and the richness of lived experiences

But then there's some stuff that is just so beautiful and clean in here. This is one of my favourites. It's a series of microgeographies. And it's three women living in Christchurch. All of different ages, and their activity spaces over the course of a 28-year period.

So bottom left, we've got Jan who's in her mid-30s, is married with a couple of children and works part-time as a librarian's assistant. And we see quite a rich set of places that over the months, Jan visits.

So there's home and her two workplaces. But there's bars, and malls, and friends, and parties, and so on. Surf championships. And the circles are sized by how many hours the person spent there.

The second person, Sylvia, is married and in her mid-50s, much more of a focus on home. But does have these different walking trips, and trips to visit family, and shopping, and a visit to a doctor's surgery, and her son's doctors. And we see glimpses into the lives of these people.

And then finally, we've got Mrs. L in blue on the bottom right who's a widow of around 70 who resides with her youngest daughter and her son-in-law. And largely, lives this housebound life where the only visits are to an Aged Concern outing, a friend's house. The Palms mall for a couple of hours and to a doctor's surgery.

And so these three maps give these, to me at least, these incredible glimpses into other people's lives and into the richness of lives and differences in lived experiences. I'm conscious of time. But I'm nearly at the end of these.

And then I'll jump over to Joan. Sorry, I could keep on blabbering on about all this stuff for ages once I get on a roll. This, I think, is also incredible within the Contemporary atlas.

Again, it's this time we've got a microgeography where it's about responses to restructuring. And it's a precision golf course factory, I think, in Riccarton, somewhere in Christchurch. And it's about how the factory floor has changed between 1983 and 1999.

So you can see in 1983, there's a lot of those green icons of people, which represent unskilled labor across the irons, the woods, and the warehousing. And then by the time that the massive restructuring that's gone on and globalisation processes of the '80s and '90s have come to rest. We're down to just three, four people across those, the irons, the woods, and the warehouse. And then the rest is clerical and management.

And as the manufacturing no longer takes place so much in New Zealand, and instead, there's just a bit of assembly and most of the clubs come in from overseas. And the atlas tells these stories in ways that could be done with words and graphs. But there's something about the map that, for me, at least really grounds these things. Similarly, there's quite interesting microgeography of the 1998 power crisis in the CBD.

Hospital restructuring

I think this will be the last map that I talk about. This is also from Russell's ‘Contemporary atlas of New Zealand’. And it's looking at public hospitals by the number and types of beds.

So we've got 1985 on the left and 1997 on the right. And it's about the change in both the number and types of hospitals. So this was actually a map that we created, except we went from 1985 to 2019.

So I'm going to show you this because I can speak to it a little more. But the data is the same. We track down the same government report as Russell had used to create his 1985 map.

And you'll see that there were, I think, 181 public hospitals prior to the rolling series of reforms that went on. And those public hospitals had 25,000 beds. And then following the four major restructures that went on through the '80s and '90s and into the 2000s.

We have in 2019 just 84 public hospitals. And the number of beds has gone from 10,700 down to — sorry, from 25,000 down to 10,700. The hospitals that do continue to exist.

There's far fewer specialist hospitals, things like mental health facilities, maternity, and geriatric. And a lot of the slack is being taken up by the private sector to varying degrees.

And I think I'm going to stop there. I had a little bit more to say. But I recognise that we are on time.

Conclusion — why make an atlas?

I guess just to end just to answer, why make an atlas. An atlas is a durable archive, especially a print atlas. It is something that I hope will persist and endure in people's homes and also in institutions like libraries and schools.

And it's a way to communicate spatial and environmental patterns and enables you to tell stories about place, about history, and people in a way that is not — it tells them through a lens which I think can be done with words and film and other forms of media. But maps are, there's certain things I think that can only be said through a map, particularly about the role of space.

I think that an atlas is a way to expose power structures and a way to expose inequality and injustice. And they are a means, or they can be a means, to challenge conventional perceptions. I think maps can raise environmental awareness. And that is something that I hope that we do in our second edition more effectively than we did in our first.

And I think that an atlas is also something that speaks to future generations. We're looking at these atlases from past decades today. Some of them 70 years old now or close to 70 years old. And their voices are things that continue.

And I'm going to look at time. I'm going to stop now and just move it over to Joan. But yeah, thank you very much. That went by a little quicker than I meant it to.

Thank you

Joan McCraken: Kia ora, Chris. That was so fantastic. Thank you.

There are lots of comments coming through and a couple of questions. But sorry we are at time. So we are going to have to finish there.

But I'd just like to say thank you again to you, Chris. Thank you very much to the people who have supported today's talk and to our audience. And I'd like to invite everyone back in November to our last talk for the year when our colleague Keith McEwen, curator of music here at the Turnbull will be sharing what is planned to celebrate 50 years since the Libraries Archive of New Zealand Music was established in 1974.

I know that Igor would have loved that talk, Chris. Thank you so much for dedicating it to him and for being with us today. And we'll finish with the Whakatauakī.

Mā te kimi ka kite

Mā te kite ka mōhio

Mā te mōhio ka mārama

We look forward to the next time you can join us. Ka kite ano.

Any errors with the transcript, let us know and we will fix them. Email us at digital-services@dia.govt.nz

The evolution of cartography

We will delve into prominent maps and atlases of Aotearoa from recent decades, considering evolution in the art and craft of cartography.

Exploring ‘behind the map’

Along the way, Chris will take us ‘behind the map’, delving into the nuances of cartographic design and its ability to provide insights and forge connections.

In memory of our colleague and friend, Igor Drecki (1966–2023), formerly Curator Cartographic and Geospatial at the Alexander Turnbull Library.

About the speakers

Dr Chris McDowall is a geographer and cartographer. He has held positions at the University of Auckland, Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research, and the National Library of New Zealand. His current role at Te Whatu Ora in Tāmaki Makaurau | Auckland involves mapping communicable diseases and environmental risks.

Chris is a co-creator of the award-winning book, We Are Here: An Atlas of Aotearoa (Massey University Press, 2019). His maps and data visualisations have been exhibited at the National Library and Auckland War Memorial Museum, and are featured widely in media.

A review of Chris’s book by Igor Drecki

Check before you come

Due to COVID-19, some of our events can be cancelled or postponed at very short notice. Please check the website for updated information about individual events before you come. For more general information about National Library services and exhibitions, have a look at our COVID-19 page.

Connecting to collections talks

Want to know more about the collections and services of the Alexander Turnbull Library and National Library of New Zealand? Keen to learn how you can connect to the collections and use them in your research or publication? Then these talks are for you. ‘Connecting to collections’ talks are held on the 3rd Tuesday of each month (February to November).

Have a look at some of the previous talks in the ‘Connecting to collections’ series.

Connecting to collections 2021

Connecting to collections 2022

Connecting to collections 2023

Dr Chris McDowall, co-author of the book, We Are Here: An Atlas of Aotearoa cover.