- Events

- Tapu 2022: Mareikura | Goddess

Tapu 2022: Mareikura | Goddess

Part of Tapu Wāhine series

Video | 1 hour 24 mins

Event recorded on Tuesday 8 March 2022

Come with us on a journey into the stories of Atua Wāhine through the lens of modern challenges faced by women.

Transcript — Tapu 2022: Mareikura | Goddess part 1

Speakers

Narrators voice, Ngāhui Murphy (Ngāti Manawa, Ngāti Ruapani ki Waikaremoana, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Kahungunu), Tui Te Hau (Ngāti Rongomaiwahine, Te Arawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa), Moana Ormsby (Ngai Tāmanuhiri, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kōnohi, Upokorehe, Ngāti Maniapoto), Te Raina Atareta Ferris (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Raukawa), Ataria Sharman Tapuika (Ngāpuhi), Vanessa Eldridge (Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Rongomaiwahine).

[Music playing]

[Birds quacking and chirping]

[Fire crackling]

Introduction

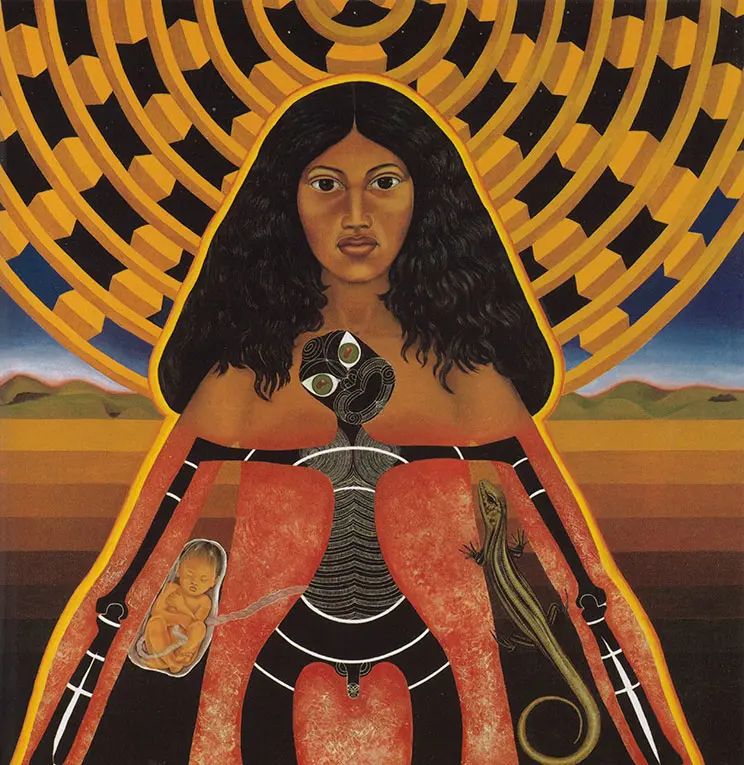

In 1984 ‘Wāhine Toa’ was conceived and created by two courageous wāhine Māori Robyn Kahukiwa (Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare) and Patricia Grace (Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Ngāti Raukawa, Te Āti Awa,

Transformational in its content and its kaupapa, Wahine Toa was the first book of Māori ‘mythology’ written and illustrated by Wāhine Māori.

The creation narratives depicted put Wāhine Māori at the centre of Te Ao Māori, revolutionising the way Wāhine Māori thought of themselves, their Tūpuna and their futures.

These narratives present Wāhine Atua, Wāhine Māori, as powerful and self-determining protagonists of their own lives.

Tapu: Mareikura / Goddess is our love letter to the work of Patricia and Robyn and to all the women who have been brave enough to share their stories. These contemporary voices are testament to the power to embolden our resolve in who we are, the stories we hold and the courage to share them.

Ngā mihi nui Robyn rāua ko Patricia

Papatūānuku

Narrators voice: Papatūānuku, there was a time when I was as one with Rangi, but now we live far apart. Between us but not separating us, were our many children to whom we had given life and nourishment and into whose hands had been given future life and growth. But this future life and growth required light and space. So our children set us apart, causing Ranginui, the father, and me, Papatūānuku, the mother, great pain and anguish.

Such was our suffering that our children turned me away from Rangi, so that we could not see one another's pain. It was our offspring Tāne-mahuta who succeeded in thrusting us apart, and it was Tāne who later formed from red earth a new life shape. It was Tāwhiri-mātea who raged in jealousy against Tāne and Tangaroa. I hid Haumia-tiketike and Rongo-mā-tāne away to keep them safe while Tangaroa drew his children to him, too, to shelter them.

Tūmatauenga, strongest of all our offspring withstood Tāwhiri's onslaught and stood astride Earth where he will stand forever, and it was this great Tūmatauenga who first of all cut the sinews which bound Rangi and me, causing the flow of blood, which ridden the now sacred ocre coloured clay. It was Tūmatauenga who assigned to me the karakia of great abundance and who originated the hunting and cooking of food.

So now Rangi dwells far above, giving space for growth. From his dwelling place, he is ever witness to life and death, joy and sorrow, hope, despair, destruction, invention, jealousy, treachery, courage, faith, and love, and the many earthly happenings. He directs the warmth and light that nourishes seeding towards and into the Earthness that I am while I remain the nursing parent, clutching to my belly, our trembling, fire-gifted child Rūaumoko.

Rangi and I are lovers set apart, yet love has not diminished. Neither has sorrow, but love and sorrow find expression still as my own mists of morning sighs rise to mingle with the caressing night dew tears of Rangi.

Ngāhuia Murphy

Ngāhuia Murphy: Te urunga tū te urunga tapu hī e hī!

Te aho tapairu o Hine-te-iwaiwa hī e hī e!

Te tuhuā i te kōmata o te rangi hī e hī e!

Ngā niho tetē o Hinenui hī e hī e!

I te kōra tīokaoka a Mahuika hī e hī e!

I te tara koikoi o Hine-nui-te-pō hī e hī!

Tēnā tātou. Ka rere rā aku mihi i te Mānuka Tūtahi i te Moana-a-Toi, te waka nei o Mātaatua ki a koutou e hau taringa mai nei ki ēnei pitopito kōrero, tēnā koutou. Ka huri ōku whakaaro ki ngā mate o te motu, o runga whānau, o runga hapū, o runga marae, ka tangi ā-ngākau atu nei ki a koutou, haere ki tō tātou tipuna kuia a Hine-whakapau-tāngata-ki-te-pō. Koutou ki a koutou, tātou te hunga ora ki a tātou, tēnā tātou. Tōku kuia, ko Panekire te maunga, ko Waikare te moana ko Ngāti Ruapani te iwi. Tōku koroua, ko Tawhiuau te maunga, ko Rangitaiki te awa, ko Ngāti Manawa te iwi. Ko Ngahuia Murphy tōku ingoa. Kia ora tātou.

It's a privilege to be a part of this kaupapa celebrating the Atua Wāhine and doing it through honouring the landmark book Wāhine Toa by Robyn Kahukiwa and Patricia Grace which brought back to us the Atua Wāhine, their stories and interpretations of their images that have been stolen from us as Wāhine through colonial Christianity that demonised the Atua Wāhine and us as creators of life.

Yeah, so it's a real privilege and honour to bring a little bit of kōrero today Papatūānuku, the mother. Papatūānuku, the mother, the source of life, the creatress of life, the oldest and most enduring of religions and spiritual traditions right around the world. And I guess the place to start is kōrero from the late tohunga, Huiarangi Waikere Puru, nō Taranaki ia, he said, ‘He mauri tangata whenua take, take’. We're not Māori. We're Tangata Whenua.

We are born from the womb of the mother Papatūānuku. The source of our identity, our sustenance, our survival, our inspiration our healing, our spiritual revelation comes from the mother Papatūānuku. We don't come from Jesus. We don't come from some random male god in the sky. Just like my kuia Rangimarie Pere said, if God was a male, men would be having the babies. That's what she actually said.

We come from the womb of the Earth, mother Papatūānuku, from Kurawaka, from Kurawaka, the vulva of the Earth, through our whakapapa to Hineahuone, the first wāhine. Kurawaka, the vulva of the mother Papatūānuku, Kurawaka, the vulva of Wāhine 'cause Kurawaka is us.

Kurawaka is our whole sexual and sensual body. And it's a stolen ground, and we need to reclaim it. We need to reclaim the sacred, original lands, the original territory, the original whare-wananga, the original stomping grounds of the people which is Kurawaka, that the feminine reproductive body, yeah, which has been demonised and stolen through colonial Christianity and patriarchy.

Kurawaka is the vulva. It's the sacred gate. It's the only way in and out of this world. It's the passage, the channel that runs between Te Ao Wairua and Te Ao Marama. We've been taught to feel ashamed of our own bodies. We find it very, very difficult to connect with our own tara with the birth canal, with the inner temple of the cosmos, the womb. We find it hard to bring our awareness there because we've been disconnected from our own sacred ground, yeah and taught to believe that it's the source of female inferiority, and that it's spiritually defiling, which is crazy because we come from that house. We come from the blood of Wāhine. If you uplift Wāhine, the people will thrive.

So one of the last things I want to say is He wāhine, he whenua. He wāhine he whenua. We are the human counterpart of the mother Papatūānuku. We're the creators of life. He wāhine he whenua. Wāhine are the human counterpart to the mother Papatūānuku. He wāhine he whenua; wāhine in the land, the source of life, and the creators of life. We are both known as the whare tangata, we kaitiaki, whakapapa and the mauri of the iwi. So if you uplift Wāhine and revere the mother, revere the whare tangata, the people will thrive. If you oppress her, that impacts the well-being of the people.

When you oppress Wāhine-- because at the moment, we've got a situation as tangata whenua, we have broken relationships to the Atua Wāhine, into the divine feminine, and we don't honour Wāhine as the source of life and the foundations of the hapu and iwi. He wāhine he whenua. And because we have broken relationships with Wāhine, the consequence of that is broken relationships to Papatūānuku, the Earth, the source of our identity, and survival, and well-being, which has led to climate crisis.

The crisis that we face as humanity isn't the climate. It's the fact that we are disconnected from the mother, so the most important thing to me is that we reconnect and restore our relationships with the Atua Wāhine and with Papatūānuku, the mother of Wāhine because Papatūānuku was the missing link. We'll never be whole until we recover our relationship with her, the source of life. No reira, mauriora te whare tangata. Mauri ora ngā Atua Wāhine. Tēnā tatou.

Hineahuone

Narrators voice: Hineahuone, I sneezed, and therefore, I lived. Tāne, the procreator, set the parents apart so that there could be light and growth, so that people could be generated on Earth. After the separation of Rangi and Papa, Tāne wished to justify his deed by joining the male and heavenly element of himself to the female, earthly element that I am in order to generate mortal beings.

He searched everywhere for me, the uha of mankind, but I was hidden from him. He found instead the uha of plant life and by joining the male element of himself to this female element, gave birth to plant life on Earth. He found the uha of various creatures of Earth and gave growth to animal life. It was Papatūānuku, the Earth Mother, who kept me hidden, keeping secret the hiding place of the uha of mankind.

Then, when all was ready on Earth for mortal beings, she told Tāne to form woman from clay at Kurawaka. So Tāne went to Kurawaka, the pubic area of Papatūānuku and formed a new shape for me from clay being assisted in this by the great being and the many godly beings of the high heavens who gifted or shaped the different parts of me.

Tāne blew on me. My eyes opened, and I drew breath. I sneezed and was alive, but Tāne's searching was not yet over. He sought a way in which to combine our two elements and so produce mortal life. He searched my body, acting in its orifices. These first contacts produced earwax, tears, mucous, saliva, sweat, and excretia. But in acting within my clitoral opening, our male and female elements came together, and Hinetītama was conceived. Within my human shape, I, Hineahuone held the first human life.

Hinetītama

Narrators voice: Hinetītama, my mother was formed from Papatūānuku by the hands of Tāne. I was formed in the womb of my mother when Tāne entered her, combining both male and female elements, but I did not know at first that Tāne was my father. I was their firstborn named Hinetītama, being the dawn and being, therefore, the daughter who bound earthly night to earthly day.

I later became the wife of Tāne not knowing that he was my father, and we parented several daughters. One day, I asked Tāne who my father was. He would not answer me directly, saying only, put your question to the posts of the house. It was then that I knew that Tāne, my husband, was also my father. I was bone of his bone, and yet I was wife to him.

I was angry and ashamed because of this and decided that I could not continue either to be wife to Tāne or earthly mother to our children. So I left the world of light, telling Tāne not to follow me. I told him to remain with our children and to care for them in the world of light. I will go on to the dark world, I said, where I will welcome our children when their earthly life is ended. I will go in order to prepare an afterlife for them where once again, I can be a loving mother. I will be known from now on as Hinenuitepō.

Tui Te Hau

Tui Te Hau: Korihi te manu, Takiri mai i te ata, ka au, ka au, ka awatea. Tīhei mauriora. Ko Nukutaurua te maunga, ko Whangawihi te awa, ko Rongowāhine ahau. Nō reira, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa. Kia ora, everyone.

My name is Tui Te Hau, and I'm the Director of Public Engagement at the National Library. I wanted to start my korero today as a love letter to Robyn. When Wāhine Toa was launched, I was a 20-something-year-old trying to find my way in the world. Robyn's paintings were thrilling. They were packed with stories and full of colour. Was the first time I remember mighty woman being portrayed in art, and also these Wāhine Atua were powerful, proud, sensual, and beautiful. And it was the first time that I'd heard some of those stories, and it was even more wonderful that they were being told by these two incredible Māori woman.

Robyn's described online as an influential figure and feminist in contemporary Māori art and that she exhibits works whose values remain central to her core practice, Wāhine Toa, woman of strength, power, and courage. Her works are internationally and nationally renown. And I'm really humbled Patricia and Robyn enabled us to use the work for inspiration for our talks.

I couldn't afford to book the first time round, and I was really pleased when it was reprinted. You should buy yourself a copy and buy three more for three people that you love. My talk is about Hinetītama and reflections on our physical self. I want to preface it all by saying it's a collection of personal thoughts that hopefully will come together and stimulate your own thinking. And these are my views, and they don't reflect the views of the library.

Hinetītama is my favorite of all of the paintings, but in my earlier days, I used to relate to her story as sad. It was about deception, lost love, losing her children, going off to be on her own. I guess our view of the world is formed by where we're at at that point in time, and I was younger and less sure of myself. And that was the lens I was looking through.

But hers is also a really powerful story of motherhood, sacrifice, determination, having really clear boundaries, self-love, rising above, and ultimately, transformation all on her terms. There was something about the story that sat a little bit uncomfortably with me, and that was the reference to incest. Even though that's not what I'm going to touch on today, it just didn't feel right to gloss over it. And at the very least, I wanted to acknowledge it.

The fact that Robyn and Patricia touched on the subject of incest at that time was way ahead of their time. They were brave and courageous women. Hinetītama felt shame, but not only did she feel shame, she expressed that she felt shame. And that's groundbreaking. Shame has, up until recent times, been a silent and solo activity.

Talking openly about shame and vulnerability is pretty commonplace today, pioneered by the work of social anthropologist Brené Brown. You might have read some of her work or seen her Netflix talk. One of her books is a collaboration with a lady called Tarana J. Burke, and it's called You Are Your Best Thing. And the book is a collection of short stories about Black people's experience of shame, and it came about during the Black Lives Matter movement.

And there's a bit that I really loved. It really resonated with me, and I wanted to share it with you. It's what Brené calls foreboding joy. She says, "we're afraid that the feeling of joy won't last, or that there won't be enough, or that the transition to disappointment or whatever it has in store for us next will be too difficult. We've learned that giving in to joy is at best setting ourselves up for disappointment or at worst, inviting disaster. And we struggle with the worthiness issue. Do we deserve joy given our inadequacies and our imperfections?"

The writer of this particular story in the book is Austin Channing Brown, and they say, "but I have discovered a far more despicable agent of foreboding joy in the form of racism. For Black people and other people of colour, there is a level of apprehension that isn't brought from the uneasy feeling of undeservedness but from the knowledge that racism is the silent stalker, always willing to wring joy from our lives. This level of foreboding joy is not in our heads. It's an evidence of our experience."

I guess one of the most straightforward examples of this in play in Aotearoa is what our parents and grandparents went through when they were physically punished for speaking te reo at school. And that intergenerational legacy is evident today even though much has been done to restore the language.

There's another aspect. In the He Tohu exhibition, I really loved the wording around the suffrage petition. It talks about the fact that woman fought for the right to have a say in the country, and I love that. The Māori woman who signed the petition is part of the Christian Temperance Movement agreed that they would not partake of alcohol, tobacco or mark themselves with the moko kauae. That was a big price to pay. Māori women were landowners, were and are landowners, decision makers, tribal leaders, and yet it's ironic that woman were fighting for rights that Māori woman already had.

I love that Robyn has never shied away from the hard or uncomfortable, and her fearless work continues as she paints about our unique Māori experience and identity and the present issues in ongoing injustices for Māori through her medium of art. Seeing yourself in your experience in the world is really important. My name Tui is much more commonplace than it used to be, but there was never a personalised mug or necklace for me.

I remember only a couple of years ago, when I worked at Te Papa, I was trying out this new digital interactive that they had made, and it assigned you one of two names by default. And one of those names was Tui. When I went to try it out and the name that popped up was Tui, which was the default, I thought that my clever mates at Te Papa were using artificial intelligence, robots or there was a camera, and someone was watching, and they knew it was me that had just stepped up.

It took me ages to finally get it that actually, that's the default. So half the people that were coming up we're going to get that name. It's kind of funny, but it's also kind of tragic. How many tamariki experience life with their name never being spoken, never being displayed in the world or mangle in mispronunciation?

But the most insidious form of shame is not the embarrassment from others. It's the shame we heap on ourselves, and nowhere is this more apparent than the relationship that woman have with their bodies. A couple of examples, I experienced period poverty all throughout school and at varsity, but it wasn't called that back then. I didn't have a name. I would really have to decide between sanitary products and something important like food or rent. And food and rent would always have to win.

It wouldn't have occurred to me to ask for help. It was my own private shame at the intersection between bodily functions and the burden of poverty. It's really awesome that it's talked about so freely today and that young girls are provided with free supplies. When I started working and earnt my own pay, I would look at my stock of sanitary pads in the bathroom, and I would think: man, Tui, you've really made it!

One of the earliest feminist books I ever read was Fat is a Feminist Issue. I feel I've spent my entire life apologising for my fleshiness and my genetics. When I was younger, a stranger came up to me one day and told me I was beautiful, that I could even be Miss New Zealand one day. But then they glanced down at my legs and turned to the other person they were with and said, hmm but her legs are fat. Skipping, skipping's really good for fat legs.

The happy embarrassment that I had started to feel was quickly replaced by self-loathing, and interestingly, from that point on and as a result of some other events that reinforced that, I made a decision that I had the wrong body or that I had the wrong head. I'm not quite sure, but essentially, I lived for many years like that and at one point, not even looking at a full-length mirror.

It occurred to me one day much, much later that actually, I could have made quite a different decision, and it could have been something like, actually: wow, Tui, your head's really amazing! Imagine what my life would have been like if I had made decisions with the glass as half full as opposed to the glass is half empty. The other thing I could have done is got angry: Who are you to judge me, stranger? But I didn't.

Over the last year, I've actually lost a lot of weight, and it's because I didn't want to be an older, immobile person I wanted to be healthy, and I wanted to be able to get around. I thought that I would be louder and sassier when I lost weight, but actually, I've become quieter because there is a less sabotaging dialogue going on in my head.

The amazing Rose Pere spoke about this and our love or hate for ourself, and she was a true inspiration to me. I Remember a talk she gave about wearing colourful clothes and putting on her make up in the morning, especially after she had recovered from a period of illness. She said, as she applied her eyeshadow: eyes, I love you. Thank you. The big question is what would Hinetītama say to all of it?

As I said, I really love that kōrero around foreboding joy and the joy that we deny ourselves because we're not enough. There's something wrong with us. We feel shame and embarrassment. When actually, I think what we can learn from Hinetītama is that we are always offered the opportunity for transformation and it's up to us to walk through their door and take it.

All of this reminded me of a quote that I found online and which I kind of played around with, and I wanted to end my kōrero on it, and it goes something like this, "I sat with my shame long enough until she told me her real name was anger. I sat with my anger long enough until she told me her real name was grief. I sat with my grief long enough until she told me, get your shit together, girl! Go out there. Be powerful." Kia ora.

Taranga

Narrators voice: Taranga, I am Taranga. I am both of this world and not of this world, inhabiting earthly land by night and by day, the land of the manapou trees. Māui-pōtiki is my youngest child, the child of my old age. I gave birth to him on the beach, secretly. He was stillborn. Without proper ritual or ceremony, I cut off my top knot of hair, wrapped him in it, and put him on the sea to be cared for by the gulls and fishes, but I knew the power of my hair.

I returned home not fully knowing what would happen but believing that this child could one day seek me out both in the earthly land and the land of the manapou trees, and indeed, one day this last born child came looking for his brothers and me. He knew our names and the circumstances of his birth so that I recognised him and wept over him.

He was strange and most magical and most loving. He was both human and godly and one day, followed me to the land of the manapou trees where I welcomed him and showed him to his father. This is our last born, I said: He is called Māui-tiki-tiki-a-Taranga, and Makeatutara said to Māui: that is a warrior's name.He will do great things for the people of Earth.

And one day, I said, he will challenge your great ancestress Hine-nui-te-pō so that people will be immortal. But later, because of our stake in the tohe ceremony, I knew that this final deed could not be accomplished. I felt much sorrow then, but I also felt great pride in knowing that this child was my own creation, that through my actions, he had been given special powers, which would be used in attaining great gifts for mankind.

Moana Ormsby

Moana Ormsby: Koutou e pae nei, tēnā koutou.

Kei ngā maunga whakahī o tēnā whaitua, o tēnā whaitua, koutou e whakarauika mai nei e mihi ana ki a tātou katoa i roto i ngā āhuatanga o te mate urutā e rērere nei. Ko ngā whakaaro nui ki a tātou katoa.

Koutou ngā mana o te puna mātauranga o Aotearoa, kia tika atu rā tēnei ki a koutou, tēnā koutou. Tēnā koutou e manaaki mai nei i ngā mātāwaka o te motu, e whakaahuru nei i ngā taonga a kui mā, a koro mā, tēnā koutou katoa. Ko Hikurangi ki te uma, ko Nukutaimemeha ki te tihi, ko te rohe o Te Mata ki te rei o Waiapu, ko te kura o te kahu, ko te huia i te awa, ko Horouta.

Ko te aru nei te taki o Uepōhatu, ko te kei o te tangata ko Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare. Ko te kiri o te kōkā nei kua pēperekōu, kua haea, waihoki nei e Awa, e Manawa, e Tūhoe, Ngati Porou nukurau, he iwi moke, he whanokē.

Like Māui, I was born in secrecy, and the choice to give me up for adoption was no less traumatic for my mother than it was for Taranga to give her baby to the sea. And like Māui, I longed to know who my people were. It wasn't a feeling of emptiness. There was no void that I needed to fill. I was content but curious, curious to know the kaleidoscope of faces that stared back at me from the mirror, the colour of my eyes, the kink in my hair, the shape of my jaw, shapeshifter, Pūnehu.

I thought of my mother often and wondered how it must have felt to walk away from the hospital with empty arms. She had to trust herself completely. When Taranga gave her baby to the ocean, she didn't know what the outcome of that decision would be. Like my mother, she had to trust in something greater than herself. All they had was hope, hope that this choice was for the best, hope for forgiveness, hope that one day, we'll meet again.

Taranga returned home believing that Māui would seek her out. My mother returned home knowing that one day, she would come find me. Taranga spent years seeing Māui in the eyes of her sons. She could imagine the shape of him, hear the sound of him through them, build a mental picture of what he might look like, measure his accomplishments by those of his brothers.

When they meet, she recognised him immediately. His brothers resented her for the attention she gave him. My siblings resented me for the pain that my mother had carried all those years, the guilt she wore every day. I used to think that if I walk past my mother in the street, she would know me. She would stop me and tell me that for the longest time, she had searched the faces of every child that she had ever passed hoping to see me.

As a customary practice, wāangai was done with the full knowledge of the hapū and the whānau. And there were several reasons to whāngai a child, but all of them focused on the extension of whānau, the strengthening of blood links. The child often knew who their parents were and their siblings. Adoption removes you from the village. It separates you from those things that link you to your origins and leaves you to recreate yourself from a mold that is unfamiliar to your bones. Adoption closes the door where whāngai holds the door open.

Perhaps, it was too painful to leave me with the village, to be confronted by her inability to care for me, or maybe she believed that she deserved to be punished. After all, she'd left a marriage with two children, pregnant with somebody else's child and then found herself pregnant with me soon after having my sister. I think she felt that closing the door was her only option.

My adoption was celebrated by the family who raised me. There was a story told over and over again, animated, reliving every moment as if it had happened yesterday, never ever I judging my mother for the gift that she had given them. She was present in their prayers, and by their example, she was present in mine. How incredibly fortunate was I to be adopted by people who came from the same place as me, whose faces looked like mine, whose bones felt familiar, and then to be whāngai to my nan who raised me Ringatū from Monday to Saturday and Anglican on Sunday.

God, church, language, culture, all that was present in my everyday life but absent in the lives of my siblings. I had a solid understanding of who I was and where I came from. My siblings continue to struggle with all things that are natural to me. We are grown now. The resentment has faded, replaced by acceptance and love. My sisters are the gift our dying father left as we worked together to make his final days comfortable. I am the middle child, and for the first time, I have a tuakana.

We are mothers and grandmothers, and I've learned that I look more like my mother than they do. I sound like her, and I peer over the top of my glasses like she did. My tuakana is logical, methodical. She likes the security of planning and routine. My teina is impulsive, emotional, and adventurous. I am the perfect blend of them both. I'm grateful always for the life that I was given and for the life that I have. The women who raised me, my mama, my nan, and the woman who made it possible, my mom.

Nō ngā rangi tūhāhā te wairua o te tangata. I tōna whakairatanga ka hono te wairua me te tinana o te tangata. I tērā wā tonu ka tau tōna mauri, tōna tapu, tōna wehi, tōna ihomatua, tōna mana, tōna ihi, tōna whatumanawa, tōna hinengaro, tōna auahatanga, tōna ngākau, tōna pūmanawa. Nā, ka tipu ngātahi te wairua me te tinana i roto i te kōpū o te whaea. Nō reira, aku iti, aku rahi, aku whakateitei, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa.

Mahuika

Mahuika, where do you come from, I called, and he replied, I come from the West. Then come and tell me what you want, I said, because you are a relative of mine. You must be Māui-pōtiki. I have heard of your deeds on Earth. I am Mahuika who keeps fire. Fire has been lost to the world, Māui said, so I have come to ask you for a flame. So I pulled out one of my flaring fingernails and gave it to him. He thanked me and went on his way, but when he was out of sight, he doused the fire in a stream.

I did not know at the time that he had done this deliberately. He returned and asked me for more fire, so I pulled out my second fingernail and gave it to him. And again, once out of sight, he put out the fire. My mokai came running to me saying, he is killing your children. Māui returned again and again, and each time, because he was a relative of mine and because of a promise I had made to the people of Earth, I gave him fire. Soon, I had given him all of my fingernails except for one.

When he returned for this last nail, I became angry. You asked too much, I called, and threw the last fire nail at his feet so that fire leapt and spread about him. He turned and ran with the flames pursuing him, and as fire began to surround him, he changed into a hawk so that he could fly above it. But when the rising flames caught hold of his wing feathers and scorched him, he dived down into a lake only to find that the water was boiling.

What a dilemma he was in then. He had to beg his ancestor Tāwhiri-mātea to send rain. It was rain, the drenching rain that saved Māui and almost destroyed me. Fire was almost lost to the world, but as the flood waters rose about me, I sent the last seeds of fire into the earthly trees, the kaikomako, mahoe, totara, patete, and pukatea and asked these trees to be the guardians of fire forever.

Te Raina Atareta Ferris

Te Raina Atareta Ferris: Me aro koe ki te whiua o te ahi o Mahuika i roto i a koe.

Hear the presence of the flicker of fire that is within you. Mahuika, te atua o te ahi . Mahuika is the goddess, the Mareikura, that Atua of the flame, of the fire. Fire, her fire was depicted in her fingernails, but she is more than that because we know our energy comes out through our fingernails. But before it can get to our fingernails, it has traversed every cell of our body and every organ of our body, and when we wiri, it's Mahuika's fire being transferred where it's directed.

So she has the internal fire within you. She is a combination of energy, of pure, purifying energy that is combined in every part of your body that is ignited from day dot. And sometimes that fire burns vibrantly like the picture on the wall at the back, and sometimes that fire can dim and almost get snuffed out. And it does get snuffed out when we die, so kua mutu tōna, ōna ahua i roto i a koe.

So Mahuika is a real critical Atua in our ability to stay alive during our lifetime. The keeper of your fire is her, and whenever you need her, you should call on her and talk to her, have a communion with her, know that she even exists inside of you, inside of every cell of your body. And that's something that a lot of our wāhine don't know.

So I'm Raina Atareta Ferris, born a Sciascia. I live in Pōrangahou, and this is our marae space here called Kurawaka. And this wall behind me represents the cosmos. We talk about the Orokohanga o te Ao Māori. And that centrepiece, he picks the first voice and te Ao Māori is the voice of the wāhine, and the first voice that opens the ritual of pōwhiri is wāhine. So there's a whole significance dialogue behind that one uranga of us wāhine.

Anyway, I'm here. I've been asked to come and talk about Mahuika's contribution or manifestation to us during menopause, and all of those who have been through menopause, I'm sure have some indication of what Mahuika does during our menopausal years. So over the years, when we've researched her as Atua, she has become a beautiful Wāhine Atua to talk about during menopause, and she manifests herself during menopause through providing a mechanism that can cleanse, and purify, and reset our bodies for the next taumata.

And we feel that energy when we have hot flushes, night sweats, body sweats, mood swings, can't sleep. So anyone who has been through menopause will know what I'm talking about, and those are the times when she's active, her energy is active. Mahuika, the kā is the ignition, igniting of those energies inside you. So you are in control, and you are in control by being aware that there is this Atua inside of us, guiding their principle but also by being in communion with her and having a dialogue with her as if she was the doctor.

So instead of going to the doctor, you can go inside, and talk to her, and seek counsel because there's a fabulous whakatauki that says, if we don't go within, you go without. So internalising your mindset, your spirit, your thoughts to providing rongoa for yourself, and that's probably hard to do today because we're so conditioned to look outside for the help.

So Mahuika is the Atua that keeps your internal flame alight, keeps it glowing. It cleanses. It purifies. It burns. Burning something, it provides space to reset something new. So when we go through menopause, as wāhine, we've been through being young girls, young woman. We've had our ikura. Every month, she comes along and helps in that process of shedding the blood and cleansing the whare tangata for the next egg that may come down the ovary tubes and prepares for that session in our life when we're ready to conceive children and bear children.

And so menopause is a transition in our life. It shifts us out of that phase into the next phase, and Ruahinetanga is our word for menopause. So I'll try and use that word Ruahinetanga. When we become Wāhine, we become Ruahine, and Ruahinetanga it is the phase that we're going through, the time of transition, and that can take years. It does take years. It's not something that happens overnight.

So in order to survive the years of transition, of bodily transition, of mental transition, or spiritual transition, or emotional transition, we have to be aware of what's going on in our body. So in this instance, Mahuika is the Atua you can call upon to help cleanse, help purify, help burn the things they don't need-- you're not needing anymore. And then as you come through, make your way through the stages of Ruahinetanga, you no longer produce eggs, so our ovaries stop producing eggs. And then we end up with our hormones being out of balance, and our ovaries don't produce estrogen or progesterone.

So it can be quite a stressful time for some women to get through, quite a harrowing time for other women. Some don't get through it fully intact. Some do. The lucky ones get through it. And you come through your Ruahinetanga, and you end up in your Wairuahinetanga, which is when you're then now able to step up into the taumata of the kaikaranga and take on the role of the guardian of the wairua of the pae karangaAnd that is the process of menopause, is preparing you of Ruahinetanga, is preparing you for your Wairuahinetanga taumata.

Ah, Wairuahinetanga. So what's that about? That's about you being able to work in the realm of wairua in an instant. You, your heart, your consciousness is heightened. You become more able to see beyond the tangible. You can tap into a spirit instantly because you've elevated your consciousness to another level of awareness.

And Ruahinetanga prepares you for that. Your ovaries are no longer producing eggs. And you're now available to hold the pae karanga 24/7. Because sometimes that is the expectation that you're available 24/7, or that we operate 24/7. Because tikanga doesn't allow it. But that's the taumata, wāhine mā.

You are able to work in the element of wairua. But in your feminine grace as the hākui of yourhapū. And so, it's a taumata that has a lot of responsibility and obligation and a lot of reward too. Nō reira, ko hou te wā

Wairuahinetanga. So we have ruahinetanga, wairuahinetanga and the next taumata after that as we return as wairua hikirangi. So that's the cycle of life that we can look forward to, if we're lucky enough to grow into that era of our lives. Nō reira, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa.

Murirangawhenua

Murirangawhenua. I went for days without food, my stomach swollen with hunger. I did not know why my family was treating me like this, leaving me in my old age and blindness to starve. Then one day, when my face was turned to the West, I smelled food. And I smelled men. "There is someone near," I called. But there was no reply.

"Because you come from the West and are therefore a descendant of mine, you will be safe," I called. "I will not harm you. I will not eat you." Then I heard a movement close by. "Come near," I said. "You must be Māui. Māui the Trickster. I've heard of you."

He spoke gently in reply. And my anger left me. "Why did you treat me so badly, throwing away my food?" I asked. "Why did you leave me to starve? "It was necessary," he said. "I have come to ask for your jawbone, which will help me in what I want to achieve." So I replied, "That's right. I have been expecting you. You may as well have it, now that parts of me are already dead from starvation."

I removed the bone from my decaying jaw, the bone of enchantment and knowledge, and gave it to Māui. "Take it," I said. "It will assist you in the earthly tasks you undertake. Take it with you when you go to seek out the ancestor of eels. Take it with you when you seek the new land. Take it on your journey to the sun."

He said, "I will keep it with me always." And he took it from me and washed it in the stream. "It is my gift to you," I said. "And through you, it is my gift to the people of the earthly land."

Ataria Sharman Tapuika

Ataria Sharman Tapuika: He hōnore, he kororia ki te atua, he maungārongo ki te whenua, he whakaaro pai ki ngā tāngata katoa. E ngā atua wahine me ngā atua tāne, kei te mihi, kei te mihi. E kui mā, e koro mā, tēnā koutou. Tēnā koutou e ngā kaiwhakahaere mō tā rātou mahi i tēnei wānanga mō te kaupapa ngā atua wahine, he mihi, he mihi. Tēnā koutou katoa. Ko Whakarara me Rangiuru ngā maunga. Ko Mātaatua, ko Te Arawa ngā waka. Ko Matauri tōku moana i te rohe whenua o Te Taitokerau. Ko Kaituna te awa i te rohe whenua o Te Arawa. Ko Te Tāpui, ko Te Paamu ngā marae. Ko Ngā puhi, ko Tapuika ngā iwi. Ko Ngāti Kura, ko Ngāti Marukukere ngā hapū. Ko Ataria Sharman tōku ingoa. Kei Whangārei ahau e noho ana. Kei Whanganui-a-Tara e tipu ake ana ahau. He kaituhi, me kaiwāwahi matua ahau. Nō reira tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa.

Kia ora koutou kua hui mai nei ki tēnei hui ki te whakarongo i ngā kōrero o Murirangawhenua. Ka nui te koa mō tō koutou manawanui ki te aro mai, ki te tautoko i ngā kaupapa e pā ana ki ngā atua wahine.

Kia ora koutou. My name is Ataria. I live in Whanganui. And in 2019, I completed my master's in Māori studies on the kaupapa Mana Wāhine, and the characteristics of Atua Wāhine at Te Herenga Waka ki Pōneke.

My research involved reading a lot of pukapuka and speaking to other Wāhine Māori across all ages and their experience with the their Atua Wāhine. Since then, I found a real passion in promoting the pūrākau of our Atua Wāhine, as it is my perspective that through colonisation their narratives have been purposely withheld from wāhine Māori to disempower us. And so, wherever I can I try to share their stories.

One of the ways in which I have done this is I wrote a children's fantasy fiction novel Hine and the Tohunga portal, which was published by Huia publishers and has actually has Mahuika as one of the characters in it. So notMurirangawhenua but Mahuika.

And I also edited a collection of writings by Wāhine Māori on the Atua wāhine called the Atua Wāhine Collection. If you are interested in either of these two pukapuka, you can find more information on my website, AtariaSharman.com.

Murirangawhenua. I am going to kōrero today about Murirangawhenua, a well-known tūpuna wāhine from the [SPEAKING MAORI] of Māui. Well, in the story that we know, Murirangawhenua is an old and blind elderly woman who is dependent on her relatives to bring her kai.

And her moko Māui, her cheeky mysterious moko Māui tells the father he will take food to her. But instead, he throws the food away until she nears starvation. And only then does he approach her.

But in the story, before Māui reveals themselves, Murirangawhenua already knows that it is him. This is an important aspect, I think, because it reveals her abilities as matakite or someone with the ability to see into the future, someone with special intuitive spiritual faculties.

And one of the things that came up in my master's research was in my interviews of Wāhine Māori was that quite a few of them could identify matakite within their immediate whānau. were mothers, aunties, and grandmothers, just like Murirangawhenua.

I believe, well, what I take from this story, an important aspect is that it highlights the spiritual powers of Wāhine, such as matakite. Know that Māui asks Murirangawhenua for her jawbone because of its magical powers knowing that it will help him to achieve his goals.

And in spite of his behaviour of the food, she still gives it to him as a gift for her descendants, which also highlights unconditional love. Murirangawhenua has an unconditional love for Māui, and no matter that he starved her, she still loves him and she still wants to help him achieve his goals.

In the version of the story by Kahukiwa and Grace, 1984, the reason given in the story is that her body is already decaying. And she will no longer need it. Māui then uses this jawbone to fashion a hook, which he uses to fish up Te-Ika-a-Māuiand later as a patū to slow Te Rā, the sun.

In my perspective, Murirangawhenua jawbone is symbolic. Although kauae means jawbone in Māori, it can also mean knowledge. And instead of literally removing and giving Māui her jawbone, she gives him her knowledge. She gives him knowledge, and mātauranga, her speech, or the moving of her jaw through kōrero, through speaking, just like what I am doing right now. I am moving the jawbone.

Obviously, with age, we all know this, comes experience and learning throughout life. And so, we value the whakaaro of our elders. And we know that we have much to learn from them because they have experienced many more days and nights than we have.

So we see in the story that important knowledge that Māui themoko, the mokoof Murirangawhenua , needs in order to complete the task that we know he's destined to do are transferred to him from his elder and his kuia, Murirangawhenua, and that this happens through the removing of her jawbone and the sharing of her kōrero with him.

And it kind of demonstrate this feeling, if you remember yourself back to a time when you were sitting with elders, older, more knowledgeable people, and really felt like you kind of had this knowing, oh, I should be listening to this. I should be listening to this. Something very special was taking place around you as they spoke. And you were sitting there, a younger and less worldly person, trying to make sense of it all.

That's the feeling I'm talking about. That's the transfer of knowledge from someone older down to the next generation. And perhaps, that's what Māui felt when Murirangawhenua was sharing her jawbone with him too.

The story of Murirangawhenua is a repository of knowledge. And when this knowledge is given to Māui, he uses it to shape his world. To bring the context or the meaning of the story into our modern times, I don't personally think this is any different to mokopuna who are raised by the elders today, or privileged enough to spend a lot of time with the elders, and to learn the lessons from their elders, and then use those lessons to care for themselves and their communities to live fulfilled lives.

There are three kuia in the Māui narratives that I know of. Mahuika is fire. Murirangawhenua is the bones of the land. And Hine-nui-te-pōis the never-ending cycles of life and death. All three represent important aspects of Maori life that Māui has to learn about. And he is not just given this knowledge, he has to earn it.

Of course, as well as guiding their male descendants, the kuia has the important role of guiding younger, Māori women too. The story of Murirangawhenua and Māui is symbolic of the transfer of knowledge from an elder to their mokopuna in order to set them up for success in this world.

And this particular version, Murirangawhenua is a kuia, a wise woman. And Māui goes on to have great success and for his deeds still to be shared many hundreds or perhaps thousands of years later, if he was ever a real person, demonstrates the importance of the relationship between tamariki and our elders.

The messages in the story are still very relevant to us today. And I hope that thiskōrero on Murirangawhenua has been useful for you. And perhaps some of us spark some of your own whakaaro around this narrative. Thank you very much for listening.

Hinenuitepo

Hinenuitepo. It was because of shame that I left the world of light for the dark world and promised to await my children and their descendants, to welcome them here in Rarohenga. Now the time is near. Now, at last, does Māui come towards me, coming in the hope that he will conquer me, and that the children of hard-won light will never know death.

When I have defeated Māui, I will thereafter welcome my descendants in death. But I do not cause death and did not ordain it. Human death was ordained when human life was ordained. And we, my father husband Tāne,Taranga, who gave special birth to Māui, Makea-tū-tara speaker of the tohi rights, Māui Pōtiki and I, Hinenuitepō are merely the instruments, the practicalities, in the sequence of death.

See Māui now. In the world of life, he has achieved all he can achieve. He comes now to challenge me in the world of no light, seeking to achieve what cannot be achieved. To defeat death, he will need to gain living entry into my womb and living exit. But this he cannot do.

Now he stands at the edge of light, exuberant, changing from one disguise to another, while the little birds watch, excited and trembling. My vagina, where he must enter, is set with teeth of obsidian, and is a gateway through which only those who have already achieved death may freely pass. He will attempt to enter in life, hoping that I am asleep. But he will be cut in two, meeting his death. Only then can he be made welcome.

Come, Māui-tiketike-a-Taranga. Your bird companions chuckle and flutter at the strange sight of you. But they are not your undoing. There is one purpose only for these obsidian teeth, in this, your last journey, where you will give you a final gift to those of hers, the gift not of immortality, but of homecoming following death.

Come, survivor of seas, lengthener of days, obtainer of fire, fisher of land, keeper of the magical jawbone of Murirangawhenua . Death is yours. Your chosen death is yours. Your deeds will be spoken of in the world of light. But you will never be seen there again.

I will wait at this side of death for those who follow. Because I am the mother who welcomes and cares for those children whose earthly life has ended.

Transcript — Tapu 2022: Mareikura | Goddess part 2

Vanessa Eldridge: Nau mai rā te hā o ngā wāhine

I haere mai koe i a Hine-te-iwaiwa

I ahu mai koe i a Hine-ahu-one

Ki runga whakairia

Haumi e, hui e, tāiki e.

Tēnā koutou katoa, whānau. I te taha o taku matua, ko Carl Eldridge tōna ingoa, mai i te Eldridge whānau i Wikitōria, i Ahitereira, ko Ngāti Pākehā ia. I te taha o tōku koroua ko Te Rito o Te Rangi Te Rito tōna ingoa. Ko Kurahaupō te waka, ko Maungakāhia te maunga, ko Whangawehi te awa, ko Tuahuru te marae, ko Rongomaiwahine te iwi. I te taha o tōku kuia ko Murirangawhenua Rameka tōna ingoa. Ko Takitimu te waka, ko Puketapu te maunga, ko Ngaruroro te awa, ko Ōmāhu te marae, ko Ngāti Kahungunu te iwi.

So kia ora everybody, thank you so much, to the National Library for having me come to speak with you all today. I'm very grateful for many things. In preparation for today's kōrero, I reflected on my gratitude, particularly to Hinenuitepō and what she contributes in my life, which she manifests in my life, both as a wāhine Māori, but also as somebody that's worked in palliative care for over 10 years at Mary Potter Hospice in Wellington caring for and with our Māori whānau in this region.

It is unlikely-- and I'm not somebody that can remember a 12-minute speech. So you'll have to forgive my wandering eyes and bobbing head as I look at my notes.

So once again, I'm thrilled and honoured to be able to speak today. Thank you so much to Whaea Pat and Whaea Robyn Kahukiwa for creating this amazing pukapuka. So I reflected upon my gratitude to Hinenuitepō , how this whakapapa, to this ātua], in fact to this tūpuna] in what their whakapapa legacy is, how that rocks up in my life.

The pukapuka Wāhine Toa was my first exposure to Hinenuitepō . My grandparents were gone before I hit my teens. And pondering ātua didn't align with my mother's Anglican view of the world.

This text and others by Whaea Pat, Mihipeka Edwards, Ani Mikaere, all informed my sense of being Wāhine Māori, alongside kaumātua, my grandmother, my mum, my tuakana, the amazing Tiritoa] Wāhine in my family, alongside some awesome hoa haere and Kaiako have informed how I am in the world.

I believe the book Wāhine Toa was a pivotal text for Indigenous women everywhere, and in a sense helps to introduce me to me. The opening of Hinenuitepō’s story starts out, and it's because of shame I left the world of light for the dark world and promised to await my children and their descendants to welcome them here in Rarohenga. That was her perspective. The reader's perspective can and should be whatever we make of it.

I've thought about that shame that she feels. Was it a shame of incest? Shame of being duped? Ashamed of not knowing her true heritage or who her father was? Yet in a sense, who else could it have been? I imagine her response to the situation would align with how many, many women would respond in her position. The word incest makes many of us recoil. The shame, the guilt, and the responsibility that people carry.

But I tell myself, to not be constrained by mankind's physical or metaphysical perspectives when exploring ātua. It is an unfathomable realm of multiple potentialities. If Tāne was amongst the greatest ātua, he may well have had the very loving ability to present himself in any ahua that would be most attractive to any Hinetītama. I think of the Haututu feats of Māui the demigod. But just imagine what Tāne could have done.

Hinenuitepō has taught me that shame and whakamā should be left with the instigator, not the recipient of the harm. And I will shun shame. Yet Hinetītama accepted the truth of her situation. According to Whiti Ihimaera in Navigating the stars, she decided to create a path Tahekeroa, the path of death.

She farewelled Tāne at the gateway to Kuwatawata and said she would meet her children in the courtyard beyond at Rarohenga. She would create an alternate realm safe from the jealous taunts of Whiro, who wished harm to Tāne offspring. Her children would continue through the pathway to be met by the tūpuna] in te ao wairua.

She's taught me that we can ascend adversity, recreate ourselves, and make new futures and realities. A woman's sense of unconditional love and motherhood can, I believe, whakapapaback to Hinenuitepō .

I recall walking with my younger son one day. As a young fella, he was wont to pondering potential fates and episodes in his own head, all of his own ego and his greatness. In his mind's eye, he always emerges as an exceptionally brilliant or handsome, protective, strong, almost smart-assed character, whatever his fictional scenario needed.

Whilst out walking one day he said to me, "How much do you love me, mum?" With little thought and quick response I said, "I'd kill for you. I'd die for you." And kept on walking. He stopped. And I looked back at him, impatient to keep on moving.

He seemed a bit shocked or taken aback. He looked at me curiously and weirdly. "That's pretty raw, mum. That's pretty raw, mum. That's cold, scary shit." I thought it was plainer than breathing myself.

I said to him, "Why do you ask, son?" It seems he was thinking about a parallel existence where someone had abused or maimed he or his brother. He was wondering how differently his parents might respond to such a situation, probably hoping we'd tear them limb from limb in some boss retribution.

He asked a further question. "What if someone killed dad? Would you take them out? Would you have died for dad?" This was too easy, given the recent separation. "No, I wouldn't. And that would leave you exposed and parentless. And it's different."

Hine decided that her children's spiritual pathway to the ancestors was her most important role. She sacrificed living with them in the light for this. What a sacrifice and what aroha. Hine shows me there is no greater love than that of a mother for her child.

In palliative care, our role is to enable a good death, with a person and the whānau are prepared as best as possible for the transition. Sometimes I ponder my own good death. And I'm not the only weirdo to have started a Spotify playlist for my tangihanga.

On D-day, I want crisp cotton sheets, light, flowers, music, and a cocooning in aroha. It's a feminine space that smells good. I don't want noise, but laughter is OK. But mostly, I want advice that helps me be composed for release, a space fat with mauri.

My death will be unique to me, as yours will to you. I think about Hine. I wonder what karanga will sound like. I wonder what the karanga of my tūpuna beyond will feel like. I know some of that karanga responsibility for myself, what that is for me, and particularly welcoming my mokopuna into Te Ao Marama when the time comes.

Working for the dying isn't for everyone. Yet the manaaki of whānau and the individual when they are their most vulnerable is a rewarding privilege. It's a tapu time, and it deserves reverence. I have seen that the wider transition, although usually peaceful, may be uncomfortable. The physical transition occasionally painful. We see the best of people. And we see the worst of people.

We see people transformed and reconciled before death. And we see others die as willfully and messily as they have lived. I've seen the last generation of a lineage die. I've seen people express their love in the strangest of ways. I've seen mokopuna enabled and empowered to care for their grandparents in ways that their own parents just could not.

I sense that dying may require vigilance and protection spiritually and physically from those of ill will or ignorance. For me, my whānau and the nannies will protect me at the wharenui and Hinenuitepō has made a safe realm to grant me safe passage beyond. She will see me safely to my tūpuna, this I know.

Wāhine Māori karanga to new life, the dead, tupuna, ātua, te taiao. And we have a pivotal role in protecting wairua. Some actually deliver and release wairua at Te Kāwatawata. Some hail to pull into our closer realms to receive our dying. Some ask tūpuna to wait until the whānau are ready. Wāhine are at the crossways of life and death. And Hinenuitepō reminds me of my whakapapa role and obligations as Wāhine Māori.

The last character I reflected upon this pūrākau was, of course, Māui-tiketike-a-Taranga. Māui te wero, Māui te hautatou, Māui the ADHD is how I think of him.

For me, Māui was the annoying class clown in primary school, the older male cousin that pinged my first bra strap and relished in my blush. The adolescent man boy who left me uneasy, not knowing if he was joking about something or not. The one that tortured my teachers and left me horrified and delighted in equal measures at their audacity. He's the Tāne energy that just doesn't know when to stop.

And older, knowing I was being played for cuddles, but bought my son those essential pair of pants all the same. When at dusk, I'd give in to an intimacy, yet well aware that the dawn may bring some tired and smug regret.

Hinenuitepō was free of all of that. She dealt with absolutes and certainties, no shape-shifting dance and foolishness for her. She welcomed literally into her survivor of seas, lengthener of days, obtainer of fire, fisher of land, keeper of the magical jawbone of Murirawhenua. Māui found his teeth in the teeth of her obsidian vagina, that powerful space that still holds a timeless yet deadly fascination.

It was not nor will ever be conquered. Hinenuitepō has left me with a whakapapa of purpose and belief. In almost closing, this is a summary of how Hinenuitepō may influence our lives.

Shun shame. Don't hold that which belongs to others. Understand our obligations and rolls as tangata Māori. We can rise and create new futures out of adversity. There is no greater love than that for a mother and child. And we will sacrifice for it. We should hold tapu and make beautiful all things pertaining to death. Let's live with purpose and self-belief and also take no shit from boys.

To all of our storytellers, writers, artists, and performers, thank you for continuing to push and strive to allow our people to see and learn about ourselves through you. To end my kōrero today, I won't share a waiata. I will share a poem by Hone Tūwhare to honour the whakapapa of Hinenuitepōin each and every of you. It is called, Hinenuitepō — The Fat Bitch.

Now if-- a big, big if-- I were at rangatira, oh boy. What tribute-paying tribes would I command to kneel beneath the elegant taiaha of your succulent beauty, and to swear allegiance to your lips, your saucy eyes, your rhythmic hips and bums, all-- oh, yes, your big flat feet.

What jewels I would fling. The stars shall be your pearls, actually fragmented purple pāua shells. The world-- the world, ah yes, yes, the world shall be a huge black oyster, pearls on a muka flax string. And you shall have orange-tinted clouds to wear at sunrise for decorative purposes only, strictly, if I were a rangatira.

Nō reira, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa. Haere rā, whānau.

[Nature sounds]

Ngā mihi nui Robyn rāua ko Patricia.

Any errors with the transcript, let us know and we will fix them. Email us at digital-services@dia.govt.nz

Fighting to be heard

National Library Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa is home to He Tohu, the exhibition featuring Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the original Te Petihana Whakamana Pōti Wahine with its 26,000 signatures.

In the late 1800s women fought rigorously to be heard and to gain the opportunity to vote in the general election. More than 125 years later, women are still fighting to be heard on many topics.

Explore the stories of Atua Wāhine

As part of the celebrations for International Women’s Day, this lunchtime talk brings together a group of formidable wāhine for the transformative experience ‘Tapu 2022: Mareikura/Goddess’. Our third annual Tapu event is inspired by the book, Wāhine Toa by Robyn Kahukiwa and Patricia Grace. Come with us on a virtual journey into the stories of these Atua Wāhine through the lens of modern challenges faced by women.

Register for a link to join this talk

This event will be delivered using Zoom. You do not need to install the software in order to attend, you can opt to run zoom from your browser.

Register if you’d like to join this talk. We will send you a link to use on the day.

About the speakers

Ataria Sharman Tapuika (Ngāpuhi) is a writer of essays, poetry and articles. She is the Editor at The Pantograph Punch and creator of Awa Wahine. Ataria has a Master of Arts in Māori Studies and spent a year researching mana wahine and atua wāhine as well as interviewing Māori women about their experiences with atua wāhine. The manuscript for her children's novel Hine and the Tohunga Portal was one of five selected for Te Papa Tupu in 2018. She has self-published a collection of writing by wāhine Māori called Atua Wāhine, and has a printed magazine, Awa Wahine, coming out soon.

Maakarita Paku (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Kurī, Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Te Aitanga a Hauiti, Lakota Oyate). ‘Manaakitia rā te mana me te ora o te tangata i ōna hikoinga i te mata o te whenua.’ Maakarita is blessed with eight children, age 8 to 27, and two mokopuna. She is passionate about traditional Māori birth practices, and empowering people with well-being of integrity and identity.

Te Raina Atareta Ferris (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Raukawa).

Kai Tahu ōku iwi.

Ngāti Kere, Ngāti Takihiku, Kāti Kaweriri, Ngāti Kuia,Ngāti Koata ōku hapū.

Kurawaka tōku marae, Rongomaraeroa tōku marae tūturu.

Porangahau tōku hau kainga.

Raina runs Māori education programmes teaching the artform of Karanga, Whaikōrero, Mahi Toi, Tangata Marae, Moteatea and te reo Māori. Te Raina has been teaching her karanga program for 21 years and it came about mainly to revitalise and strengthen the capacity of kaikaranga on marae throughout the motu. He honore nui mōku. Empowering wahine Māori is the ultimate goal, alongside building capacity of the pae karanga.

Vanessa Eldridge (Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Rongomaiwahine) is the Director of Health Equity at Mary Potter Hospice. Vanessa has led and developed several programmes relating to loss and grief for Māori and compassionate communities work. She is passionate about connecting to mana whenua and Pacific communities, especially through her work in providing equitable services for all. Vanessa is Wellington born and the mother of two fine sons.

Ngahuia Murphy (Ngāti Manawa, Ngāti Ruapani ki Waikaremoana, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Kahungunu) is the author of Te Awa Atua: Menstruation in the pre-colonial Māori World (2013) and Waiwhero: He Whakahirahiratanga o te Ira Wahine: A Celebration of Womanhood (2014).

Moana Ormsby (Ngai Tāmanuhiri, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kōnohi, Upokorehe, Ngāti Maniapoto) is Development Advisor Te Awe Kōtuku at Te Papa Tongarewa. Moana is the proud mother of two sons and grandmother of two granddaughters, and loves her cat called Chowder. Her love language is food and music.

Tui Te Hau (Ngāti Rongomaiwahine, Te Arawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) is the Director of Public Engagement at the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, leading the work that connects the knowledge and taonga held within the Library with communities and visitors. Tui has built complex national innovation programmes from scratch, including Mahuki: the world’s first business accelerator for the culture sector (located within Te Papa). Tui is passionate about creative entrepreneurship and innovation, and advancing the aspirations of Māori women.

Check before you come

Due to COVID-19 some of our events can be cancelled or postponed at very short notice. Please check the website for updated information about individual events before you come.

For more general information about National Library services and exhibitions have look at our COVID-19 page.

Robyn Kahukiwa, illustration of Hinetītama from Wāhine Toa (1984). Used with permission.