- Events

- New Zealand cartographic heritage: the land, the people, the stories

New Zealand cartographic heritage: the land, the people, the stories

Part of Turnbull up close series

Video | 1 hour

Event recorded on Tuesday 12 October 2021

This online visual tour of New Zealand government maps, with Cartographic Curator Igor Drecki, will provide you with the opportunity to discover them in a new light and appreciate the creative beauty of cartography

Transcript — New Zealand cartographic heritage: the land, the people, the stories

Speakers

Joan McCracken, Igor Drecki

Welcome

Joan McCracken: Kia ora koutou. Ko Joan McCracken aho. I'm with the Alexander Turnbull Library's outreach services team. And it's my real pleasure to welcome you all to our very first Turnbull Up Close online. And now hopefully you can see me as well as hear me. Turnbull Up Close is usually held on site and the hour long sessions hosted by the libraries curators give a small group of people the chance to get a special up close introduction to some of the library's wonderful collections.

COVID restrictions mean that this isn't possible this month. But instead we have an opportunity to take a closer look at part of the library's extensive collection of maps online with curator Igor Drecki. A little housekeeping before Igor's presentation. As you will have seen when you joined the webinar, we are recording it.

And as this is a webinar, your videos and microphones are turned off. However, there's still an opportunity to interact with those of us in the room and with the others in the audience. If you'd like to share where you're joining us from, have any general questions or comments, then please add them to the chat.

If you have any questions for Igor, then add those to Q&A. You'll find both buttons at the bottom of your Zoom screen. Our colleague [INAUDIBLE] will be monitoring chat and Q&A. At the end of the presentation, I'll come back to ask Igor any questions we receive.

I am now delighted to introduce the curator cartographic and geospatial collections at the Alexander Turnbull Library Igor Drecki. Igor trained as a professional cartographer and worked in the private local government and academic sectors before joining the library earlier this year. As he says, cartography and maps have always been at the heart of my professional pursuits. We're really looking forward to your presentation, Igor.

Introduction

Igor Drecki: Good afternoon, everyone. My name is Igor Drecki. I was already introduced. I'm curator cartographic and geospatial collections at the Alexander Turnbull Library. And I'm also a professional cartographer. And a lot that you will hear from me today will actually be from me as a cartographer, not only a person that looks after cartographic heritage.

I'd like to start with looking at what East New Zealand cartographic heritage. So the cartographic heritage for me is something to do with the nation, with its history and character, with the tradition, its achievements, and the objects. And I like to put maps in the middle of it just for the sake of being cartographer.

Cartography on the other hand, is interweaving art, and science, and technology. Puts maps in the heart of cartography because this combination of art, science, and technology is used in order to make maps, to study them, and to use them. So all taken together, the New Zealand cartographic heritage to me is the way cartography is contributing to shaping the nation, and touching the hearts and minds of New Zealanders.

The land

And I'd like to now move into three parts. The first one being about the maps, about the land. All these maps that you will see very shortly are coming from our collections, from the digitization program, we ran in partnership with University of Auckland, but with a support of a wide range of institutions like LINZ, New Zealand Defense Force, University of Otago.

So we cartographers like to look at the maps as-- and put them in some sort of types. So here they are general maps that shows the landmass of, in this case, New Zealand. Very general. Not too much detail. Just to give a bit of understanding of where we are in the world.

We've got topographic maps that look at inventory of our landscape, of our developments. We've got cadastral maps that shows property boundaries and land ownership. We've got mosaic maps, maps that were created using aerial photography and then somehow put together into geographic space, so we can actually make sense of the location and how the land looks like from the bird's eye.

We've got street maps, which are currently under a bit of stress through our vehicle navigation systems and so on. But we do have them. We have land inventory maps. Maps that record our soils, our land suitability. Very important treasure that we have in our land. We've got also maps that look above the ground. They are aeronautical charts that talk about navigating the airspace. And similarly, we've got hydrographic charts that actually look at navigating the sea surrounding New Zealand.

Government through these maps that produced over the last 150 years also to care for a long time producing maps for our New Zealand defense forces. And here is an example of one of the training area maps. We are probably familiar with the recreation maps. The ones that accompany us on our trips here and there on our walking tracks, on our escapades.

There are some manuscript maps produced for brochures, posters, publications with amazing artistry embedded in them.

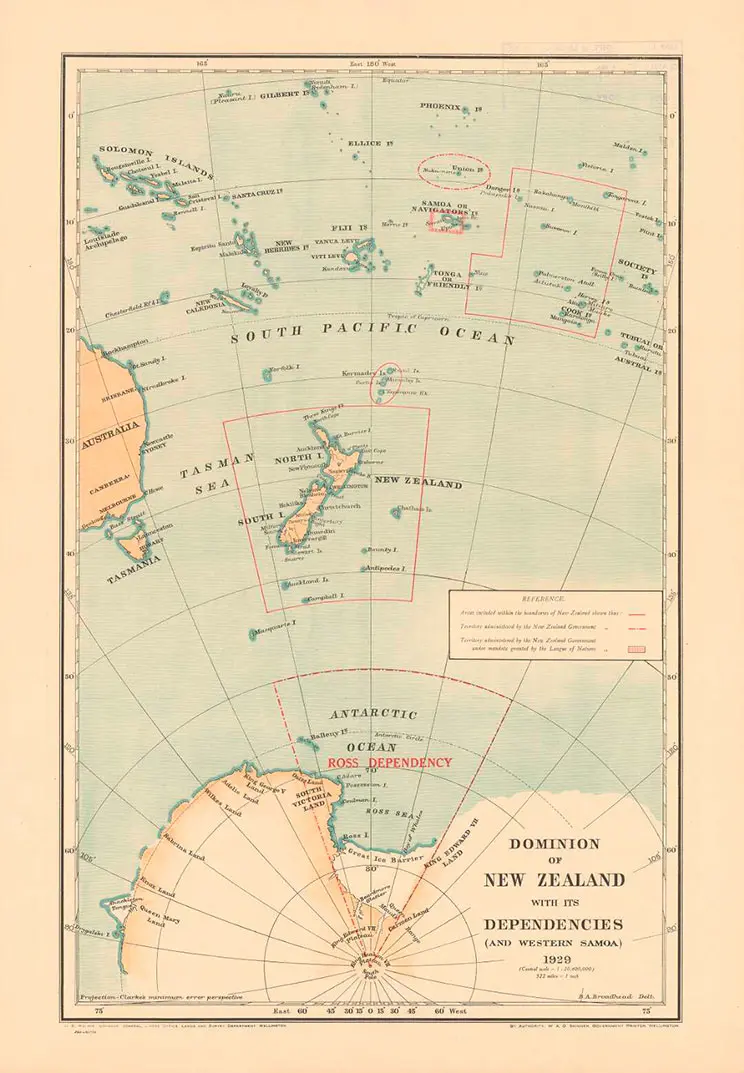

So apart from New Zealand maps, talking about geography here. The New Zealand government took care of mapping our offshore islands. About mapping our neighbors like South Pacific, in this case, a map of Samoa and land ownership over there from 1921. We obviously have interest in mapping Antarctica, in particular Ross Dependency. This map is a collaborative work between the US Geological Survey, and LINZ, or its predecessor the Land and Survey.

Thematically, we've got maps of conflict, like one here. New Zealand wars from 1869. We've got maps of sorrow. The maps that show in this case, the aftermath of the Christchurch earthquake, with disused roads showing the suburbs that were occupied by happy families. They are now gone.

We've got maps of celebration. Maps that show, in this case, our first National Park, and some say fifth in the world to be established. A magnificent gift as well. We've got maps of achievement. In this case, we've got railway lines of the North Island. It's quite interesting to look at this map and see the planned railway line between Te Awamutu and Hastings. I wish it was built at any pace.

We've got maps of reconciliation. The map that shows Māori names on modern maps. And we've got maps of experimentation. The maps that sometimes were produced ahead of their time, like this one that is 62 years old-- sorry 52 years old. And it's something that I would argue that, for presentation of topographic high terrain model or high terrain landscape, is still something we've got a bit of a catch up to do. But it was produced by our cartographers.

The people

And since I mentioned the cartographers, I'd like to spend the second part of my presentation on people, on cartographers. People behind all these maps. And in this case, I'd like to present to you my own take of what it means to be a cartographer. What is important to us cartographers. What is important to me.

The map makers

The act of creating a map is something that I cherish a lot as a cartographer. Every new mapping project is like discovering the beauty of cartography from scratch. Reassuring me that I am in the right profession and providing opportunity to apply my creative talents.

It is also like Thanksgiving for the gift of creativity, because creativity is not something that can be learned at a University, or through in-house training. It can only be discovered and nourished, worked and perfected, multiplied and freely given out. It is at the heart of cartography that so elegantly and ingeniously mixes art with science and technology.

To me, creativity requires our constant attention, care, and development. Only then, we are truly embracing the gifts, and through our maps share it.

The spirit of being a cartographer is to serve, using our talents and unleashing the power of our discipline to create well-researched, useful, and aesthetically pleasing maps provides the right environment to serve.

Whether it's a tramper using our map on the Tongariro Walking Track, or a curious teacher examining our Atlas to tell a story to their class. These are just examples of experiencing the true joy of getting a reward often unnoticeable to the actual users for our cartographic work.

With the call to serve comes responsibility. It is up to me to represent the truth, to the best of my knowledge, using not only cartographic principles, but also ethical ones. Our maps, globes, displays, and visualisations are here to enlighten, inspire, educate, challenge, inform, fulfill, to guide. I am very much aware of my role and my duty to serve.

Being cartographer often demands from me taking a stand, defending my design choices, and protecting my professionalism, and integrity to remain faithful to the ethical principles of my beloved discipline. This is not easy. The discrepancy between customer wishes and the best cartographic practice sometimes creates an ethical dilemma.

To me however, this dilemma is only theoretical. As a cartographer and a professional, I have a duty to maintain graphical integrity of my products. The purpose of the map, its scale, and target audience determines the design approach I need to employ and execute. I cannot change it. Otherwise, it is not cartography.

I believe that adherence to the truth and ethical principles should always be exercised. Only then can I remain faithful to cartography and help in maintaining the respect it deserves.

The community

Cartographers are quiet achievers that strive for the best and are always surprised by recognition. It is wonderful that we also have a community out there that really cherish our work. And whether it is someone painting the maps, like here Mark Wooller's work. Or someone enhancing them, like, Andrew Tyrrell, spending time with the 1960s NZMS 1 to an inch mile series, sheet of Christchurch and applying the modern relief shading and digital terrain model to actually make it 3 dimensional.

With some, we've got some people that photograph the maps. Like here, they're largest Atlas in the world that we've got in our collection. Some use the maps in their escapades to the high peaks of our mountains. Some getting excited about them and others simply wear them.

It seems that all enjoy maps. We all cherish maps. And it's a matter of just sharing this joy of interacting with maps, and sometimes with cartographers. This photo of four nice people smiling is also a testimony to the institutional support we are getting as cartographers. Each one of them represents different parts of the industry. We've got policy makers here. We've got curators. We've got freelance cartographers. We've got also government cartographers.

And this institutional knowledge is shared and cherished by our community. And Turnbull is not-- it's playing its part as well. Here we've got Chris Szekely opening the National Cartographic Conference in 19-- sorry-- in 2016. We've got Mark Crookston that opened our conference in 2018 sharing powerful stories about his understanding of maps and how maps played a role in his life to some degree.

Through organizations such as National Library, Turnbull Library, Land Information New Zealand, we also managed to attract our politicians, in this case honorable Eugenie Sage, Minister of Land Information in the previous government who came to share her time with us at our conference.

And there are some space for friendly chats, like Chris is talking here with Professor Menno-Jan Kraak, president of the International Cartographic Association that was our guest of honor here in New Zealand at our conference. So we really much sharing-- sorry. We are very thankful for this wonderful community. And through them, we can discover and cherish, embrace, and share the beauty, value, and depth of New Zealand cartography.

The stories

And now we're moving to the stories, stories that are embedded in maps. And I suspect some of them are very well known to you. And perhaps there will be toll to gain. But I hope there will be something fresh in the way, how I'd like to present them to you. Through the lens of cartography. Through the lens of cartography.

The shifting sands

Here's the story of the shifting sands that shows the dynamic environment we live in. It's not only that our Southern Alps are moving up by about 4 to 6 millimeters a year. But it's also our coast that is maybe even more-- these dynamics are even more pronounced.

In the space of 27 years, between the first map on the left and the one on the right, we had amazing changes to the North Head of the Manukau Harbor. We can see the accumulation of sand, the change of the coastline, the differences in the little lakes and the outlets of streams going into the sea.

The map on the right has got about 2 square kilometers more sand than land than the one on the left. 2 square kilometers. That's equivalent of 2000 of generous quarter of an acre sections. So it's quite a lot. Plenty to fill in a lot of sandpits for kids.

The disappearing (Ben) island

Here is the story of the disappearing island, and amongst a few we call it Ben Island. The map was there, and it's still there. Although it disappeared for 30 years. It disappeared somewhere between 1977 and 1984 from our maps. It may be from someone's memory. There was a period when following the metrication in New Zealand.

New Zealand's cartographic scene and obviously the government responsible for official mapping of New Zealand had a wonderful opportunity to redraw the maps from scratch. One of the things that were used in order to make the new maps, the 1 to 50,000 topo maps were the aerial photography.

And it seems that the people that drew this particular sheets face an interesting challenge that a cloud obscured the island when they were drawing it so they missed the island. And not only a cartographer missed it, because we do miss things. But also the people that check our work, the quality checking, failed.

And it took Ben Jones, one of the digitization technicians behind doing this wonderful digitization program that I'm sharing with you all these maps from. It took him to actually notice that. And we contacted LINZ in 2000-- sometime between maybe 2015, and said, hey, can you investigate it.

The island is shown on the bottom left corner on a photography taken in the 2014, 2016 photography season. So the [INAUDIBLE] is still there. We checked it yesterday. I checked it yesterday, and it's still there. And we were pleased that LINZ put it back on. So sometimes we-- in this case, we also argue to LINZ that maybe it should be called Ben Island, because Ben found it. But unfortunately our request and our suggestion is still unanswered, maybe one day.

The reappearing naval base

Here's the story of a reappearing Naval base. The first image, one of the mosaic maps is from 1951. A few short years after the drama of World War II. At the time, obviously, the National Security was still something of importance. So the decision was made to obscure the area of the Devonport Naval base, and also some areas North of it, towards the top edge of this image.

Also facilities on the North Head have been obscured by vegetation and patches of sand. Interestingly, even Torpedo Wharf, you can see perhaps a black marker over the name, because torpedo could actually give something away about what it is all about. And the Naval base reappeared in 1972 when all this scare was over, and we could actually show things as they really are.

The Napier Earthquake 1931

There is also human stories. In this case, in the Napier earthquake. And it's a story of early surveys of this part of the country. And the map on the left shows a triangulation map. Still pretty much an island up there in 1878. And then a map that was curiously printed in 1932, but the map was done prior to the earthquake of 1931. The slide shows the big lagoon there.

So this is a cadastral map showing, obviously, the land subdivisions and their properties. And then the earthquake came. An earthquake that had a devastating effect on Napier. So the earthquake damaged-- the damage was probably not as substantial as the aftermath of the fire that actually completely destroyed the city.

What happened next is that surveys came back, and did a wonderful job of surveying the uplifted land, making sure that everything is again, measured properly and according to the best practice and standards back in 1933. The new map has been drawn. Where the bay or the harbor disappeared, is all dry land. And big plots of land have been assigned to these areas.

So what about the people? The people cleared the city, the rubble. They were determined to rebuild the city. They built the Arch, called New Napier Arch, and on top of it there is this saying, "Courage is the thing. All goes when courage goes." This is a nation building, shaping the nation type of thing that happened in Napier. Where people picked up, rebuilt, and rebuilt with wonderful flair.

And we've got Art Deco Capital of New Zealand, maybe of the world. And that resilience is shown through celebration that is going through Napier these days with the lovely times of people dressing up, fashioned 1930 type of dress, cars, and architecture.

Remarkably, Napier Earthquake also provided, as I mentioned, this state of the art survey that was able to provide an impetus for initiative towards the end of the '30s to provide a first comprehensive of New Zealand at 1 to 1 inch to a mile series. And the very first sheet was produced in Napier and Hastings area in 1939. The only sheet without a grid.

The humour

There is some humor on the maps. And here we've got a map that shows a little bird in the corner of a particular sheet. We've got fish remains sitting on the rocks. We've got initials, probably hard to see, very small in the rock drawing in the Quail Island in the Lyttelton Harbor. We've got also a name, LES, drawn in the cliffs of Flea Bay on the South part of the Banks Peninsula.

The deeper issue

And I guess when we think about it, perhaps it's not only about the humor. Perhaps there is a deeper meaning in all that. And looking at this 1902 map, we see at least five names on this map. We've got the name of the surveyor general. We've got the name of the chief surveyor, of chief draftsmen. We've got a name of a cartographer. We've got the name of the government printer.

These names are proudly displayed on these maps. And I don't have a sample of the map, contemporary map that shows the names, because they are not there. We know more about cartographers of the past than we know about cartographers now.

Map projections

Map projections. My favorites. Perhaps a little technical. But if you think about it, earth is obviously, spherical. So in order to represent the Earth on the flat sheet of paper, some distortion occurs. And they are taken care of by map projections. Map projections, these are a technical aspect of cartography, and the aim is to limit the distortion to the minimum.

In 1942, Edward Walsh came up with a Transverse Mercator projection for New Zealand, separate to the North and South Island. He did that in order to minimize the scale distortion, which is one of the elements of measuring the quality of the map projection. And he achieved what was then an amazing result of having 1.7 meter out over 1 kilometer. So that's 1 kilometer in reality on the map in the worst case scenario was 1 kilometer, 1 meter, and 1.7 meters. So it was longer by that amount.

Then it comes 1973. And as I mentioned the metrication gave impetus for the redesign of New Zealand topographic maps. And here comes Ian Reilly from DSIR, who developed a projection that minimized the worst error in New Zealand for 1 kilometer of 23 centimeters. So that in worst case scenario that 1 kilometer is just slightly longer by 23 centimeters. That's 50 years ago.

And this projection called New Zealand Map Projection was not unfortunately named Ian Reilly projection. But I learned about it during my studies in Poland. Because it was one of the most amazing projections and testimony to the ingenuity of people behind these sort of calculations.

And now we're moving to the current New Zealand Transverse Mercator projection. Not only we don't know who actually designed it, and maybe some will say or maybe it's Mercator himself. But looking at the scale distortion for the projection we've got now, I'm a little bit worried. Worried about the fact that we do not cherish what was the world class amazing projection developed in the '70s, and cannot match it with all this technology, and sub-centimeter a precision of geodesy surveying these days.

The design

The design. Here's a topographic map, 1 inch to a mile from 1884. The design here also is a testimony to the technology that was used and is used in order to make maps. Here, we've got hachuring, a technique used to show the slopes and the aspect of terrain. So the darker parts of the terrain, the darker lines drawn on this image, on this map shows steeper slopes. The lighter ones would show more gentle slopes.

Incredibly we can easily see the ridges. We can see the valleys. And we watch, fast forward 60 years to this NZMS 1-1 inch to a mile series. It was done in a bit of a hurry. So the third dimension is gone. Well, it's shown by contours. But there is no relief shading. There is no hachuring, there's no three dimensional feel to the map.

The rapid leap here is the leap in the technology that was possible to have a very precise picture of land in this case marked through the contour lines. And obviously the shingles in the river and other features that actually were impossible to draw at that level of accuracy back in the 1880s.

And we're moving forward another 30 years, or 40 years, or 50 years. And we've got a New Zealand topographic map at 50,000. Where we refined that precision accuracy. We've got better techniques in order to more precisely determine the shape of our Earth. To show the landscape of our cherished land.

And here is also the land relief. And we can see some ridges. And we can see the valleys. And putting these maps together it shows the development that has been aided by technology moving forward. But looking at this 1884 format, it's something artistic in it that is somehow missing from all the maps produced afterwards.

Something that magically shows this terrain in some way that is not as visible in the other maps produced later. Maybe something more similar to the map of experimentation that I showed you before. I'm really curious, how our maps will look in 2035. How much of our creativity will help us to aid that design, to harness the technology, and pronounce the art that is such a critical part of cartography.

Conclusion

I hope that my talk just to some degree helps to maybe answer, to show, to illuminate the way cartography is contributing to shaping the nation. They're touching the hearts and minds of New Zealanders.

The maps used in this presentation come from a collaborative government map digitization program run between 2010 and 2016. Most maps are available from Alexander Turnbull Library as physical and/or digital copies augmented by onscreen viewer. And many are downloadable from the University of Auckland Library's GeoDataHub.

The people that I showed in this presentation are New Zealand cartographers and members, and supporters of the local cartographic community. Thanks to them we discover and cherish, embrace and share the beauty, value, and depth of New Zealand cartographic heritage. They are the people whose names are no longer on maps that we know so little about them.

And interestingly the names of cartographers disappeared from New Zealand government maps in the 1960s. The last name of the surveyor general was on the map published in 2000-- sorry-- in 1997. There was a brief period where nautical cartographers were able to put their names on hydrographic charts in the late '80s, but their names disappeared for good from 1998.

And the stories, the stories that I presented here are my own, or told to me, and shared with me by fellow cartographers. And I do appreciate that some are widely known, but perhaps I managed to tell them from a cartographic perspective, a fresh perspective for some of you.

So I'd like to thank Plant Information New Zealand, topographic office, hydrographic authority for their work. For these amazing maps that they keep producing. For New Zealand Defence Force for looking after the maps. Producing the maps that enable us to look after our country from the defence perspective.

Thank you to the University of Auckland, School of Environment and the Library for supporting the large digitalization program that I could actually use now the fruits of it in this presentation. University of Otago, the National School of Surveying and Hocken Library for supporting us. Understanding technical aspects of georeferencing and good chats about surveying and treasures in Hocken Library. The National Library of New Zealand. Well I am part of it now. So I'll stop here.

I'd like to mention the cartographers by name. The ones that I showed the pictures of and the ones like Margaret Chappell, Bill Drake. Bill Drake's amazing relief shading of Mount Cook that I showed before.

Michael Farrell, Dave Lawrence, Mark Martin, Dave Moll, Lesley Murphy, Andrew Shelley, Roger Sheppard, Roger Smith, Janet Studman, Andrew Tyrrell. I'd like to thank artist Mark Wooller. And special thanks to Ben, Geoff, Graeme, Joan, Julie, and Leslie for this amazing opportunity and your support. And finally, to today's audience for tuning in. Thank you.

Questions

Joan McCracken: Kia ora Igor, thank you so much for that wonderful talk. We have had a little bit of a sound problem at the end. So if people can't hear us, will you let us know. If you can hear us, can you let us know. There's lots of fantastic comments in the chat, Igor. But we've also got some actual questions for you.

So first from Caroline, did the separate grid projection for the North and South Island cause more distortion for Cook Strait? I'm wondering if that's why they abandoned it.

Igor Drecki: It presented a big challenge, interestingly, mainly for navigation and aeronautical navigation more than topographic mapping. However, I think that is the main purpose of changing the projection. To use the metric projection in the '70s was to harness the opportunity of moving into the metric system, and obviously taking advantage of the developments in the-- and technology, and state of the art back in the '70s.

Joan McCracken: Thank you. And from Julie, thanks so much for your wonderful presentation. Could you please comment on the reason why cartographers names are no longer listed on maps and why this has changed?

Igor Drecki: That is a very interesting question. And helping with cartographers these days tend with-- make producers. In the very rigorous environment like government cartography, less and less is produced by a single person. More and more is produced by teams that work together in order to produce databases from which the maps are then drawn.

So it is possibly harder to identify individuals to put on the maps. But still, I believe there is room for having some ability for cartographers to show ownership, accountability, and pride in what they are doing. And if there is a will, there is a way. Even in such environments like Land Information New Zealand or Defense Force.

So on the other hand, private cartography still cherishes that tradition. And maps produced by freelance cartographers always display the names, because we like to be accountable for what we're doing. Because of our strive for truth, for integrity, for honesty, for professional ethics.

Joan McCracken: I'll unmute. That might help. We've had someone suggesting that people are just sneaking their initials or their names into the corners of maps. Do you think that does happen more than the example you showed us?

Igor Drecki: It's very hard to actually find these things on the maps. And I actually I believe that it is not a practice that is being exercised now. It was maybe a little bit easier before. But I do heard the story of a cartographer putting the name Veronica in Nelson Lakes National Park. It was a fake lake. And he named it Veronica because his daughter was named Veronica.

I have not came across this map. And I don't know whether it's a legend or true. But it's a wonderful that still cartographers somehow try to take that ownership even if it was against the rule.

Joan McCracken: It is quit a nice segue if someone has a map with the Lake Veronica on it and would like to donate it to the Alexander Turnbull Library, is that a possibility? Are we still collecting maps of these kinds?

Igor Drecki: We are always on the search for maps. And even if we are one of the most complete collections of maps, I am still surprised almost daily by people ringing and saying, I've got this map. There was a person just recently saying, I've got a Whitcombe and Tombs map number 22. Do you have any in your collection? Not only we don't have the map number 22. We don't have any, from 1 to 23 that we established that possibly were ever published.

So always comes to us. If you are interested, if you believe that the map you have needs some protection and contributes to the New Zealand cartographic heritage, we are always happy to hear from you.

Joan McCracken: Thank you. There is another question here. Thank you, Igor. I am interested in the geospatial part of your role. Could you comment on this aspect, please?

Igor Drecki: My role as a cartographic and geospatial collections curator at Alexander Turnbull Library heralded a change of thinking in the library itself, in the National Library, Turnbull Library. We need to do some work around this. And we appreciate that more and more maps are done from geospatial data sets and databases. And we-- honestly speaking, we failed so far in capturing this information. In capturing these databases.

And we are the role. Hopefully, we'll bring a change in this area. And we will definitely try to do much better from now on with preserving and looking after geospatial collections New Zealanders are producing.

Joan McCracken: Thank you. If anyone's got any more questions. We do have a little more time. If you've put your question in chat, and I've missed it, could you please use the Q&A function? In the meantime, your biographies of cartographers, are there many of those? Has cartographers been the focus of many writings?

Igor Drecki: Of many?

Joan McCracken: Well, anyone written biographies about cartographers? And we've got a-- actually, I'll go on to Miriam's question because it is an extension of that. As someone interested especially in kids books, where endpapers sometimes, but not often enough, include maps of the world place they're set, I am curious whether those are made up maps in your own section for made up maps in the collection?

And also whether as a cartographer, yourself, have you made maps of places just for fun?

Igor Drecki: Yes, there are maps of fake areas. And perhaps it is no surprise, especially to fellow cartographers from the defence force where they use fake maps for training purposes and so on. And I've seen many of them in my lifetime. So yes. And we've got obviously, maps-- the token maps and of-- maps that are of non-existing worlds out there. Maps that are used to illustrate games.

So yes, there are maps of non-existing places as well. Whether, we've got them in our collection? That's a good question. I started here in April, so I've got a lot to do to accustom myself with about 80,000 maps that we've got. And honestly, I have not come across one of such places yet, but hopefully, I will.

And the question about cartographer, whether I've made a map like this? No. But I am guilty of putting a mark myself on some maps. I used to work for Wises publications, publisher of street maps, business directories, road maps. And particularly on the street maps there were street numbers put along the streets.

And when I was a cartographer I put street numbers corresponding to addresses of my family and friends around Auckland. So then they could say, hey, if you want to visit me just look at the map, and there will be my number there. And so I've got a confession to make here.

Joan McCracken: I think an exhibition of maps by Igor might be coming up in our future. Just to comment on Miriam's comment-- question about endpapers and maps. We had a lovely display here just very recently from the children's literature collections of maps and books for children. So there is a different sort of collection, but it's been noted that there are wonderful maps in children's books.

And just to go back to my previous question-- we've got a couple more minutes-- I was asking about biographies of cartographers, and people who are interested in learning more about the people who make maps. Are there biographies of cartographers?

Igor Drecki: Not many, if there are. I think that surveyors received much better attention of historians in New Zealand. And many of the early surveyors, especially land surveyors were also cartographers. Although, obviously, even going back to the nautical cartographers, and navigators. They were also attributed with many maps that were produced off of hydrograph charts of New Zealand waters.

However, books about cartographers and such-- I've got a couple of manuscripts of people that spend their life drawing maps, but they have not been published in-- and available to the general public. The New Zealand Cartographic Society, which I haven't mentioned has got initiative, publishing initiative that is actually trying to perhaps bridge that gap, and talking about some of the designs like the 260 book edited by [? Graeme ?] [INAUDIBLE] that talks about cartographers, how they came up with certain designs, and so on.

But perhaps it is more about the work and maybe this is what you are asking for and that's perfectly fine. However, not from the perspective of biography as such so there is a lot to do in this area, I'm sure.

Joan McCracken: Thank you. We've got three more questions. We've got 4 minutes. So a minute each. So I can say thank you. So does the National Library Collection also include maps that have only been digitally produced or is it only physical maps?

Igor Drecki: So the National Library Collection as I mentioned, it's about 80,000 physical items about 16,000 of them are manuscripts, the rest are published maps. However, we do have some digital maps that are only available digitally. And obviously, we've got a lot that are only physical without the digital surrogate.

It presents a certain dilemma. Whether a map that we've got available only digitally is a genuine item within the collection if we don't have a physical item there. And I'm not talking, obviously, about the digital maps. I'm talking about the maps that are scans of physical maps. However, I still believe there is a value in enriching our collections by maps that we cannot quite have in our collection, or do not have currently, and still be able to at least show what they are through their digital surrogates

Joan McCracken: Thank you. That's a question that we've discussed a little bit ourselves haven't we, Igor. Another question, early surveyors made maps. Does Alexander Turnbull Library have any original surveyors field notes notebooks and maps?

Igor Drecki: Yes, we do. We are not probably as-- we don't have as many as National Archives, which are obviously the repository for government departments. And to many of these early surveyors were employed by the government, and that's why they are subject to collections by the National Archives.

But we do have some of them, like Charles Heaphy and Buchanan. We do have some of their original work here in our collection.

Joan McCracken: And some beautiful art works, as well by those people.

Igor Drecki: Absolutely.

Joan McCracken: And the very last question for today, do you or Turnbull Library hold a big collection of geological and geophysical maps?

Igor Drecki: Yes, we do. But probably mostly published materials. Still GNS science is the place to go for unpublished materials. And I understand they've got over 9,000 maps and charts that they have in their collection that are unpublished materials. So they are still custodians, and they're looking after this material themselves.

End of talk

Joan McCracken: Thank you. We're right on time. So I will just say thank you so much, Igor, for a fascinating presentation. And thank you to everyone who joined us today and for your contributions. You should receive a short survey, just two questions, when you leave the session. We would appreciate it if you have time to respond.

If you'd like to hear about future events being held at the library on site or online, and you are not already on our What's On mailing list, please do sign up. Lynnette, can you add the address to chat before people go? So ATL outreach address?

Thank you. And you can also subscribe to the events pages on the National Library website, www.natlib.govt.nz. A number of people have asked if we're making this recording available? We're working on it. We certainly hope to be able to do so. If you're really keen to get a copy, please let me know. Otherwise, look out for it on our website in the future.

So it's just up to me now. Thank you so much again, Igor. We really had a wonderful session with you. And we look forward to the next time you and the audience can join us. Ka kite ano.

Igor Drecki: Thank you.

Any errors with the transcript, let us know and we will fix them: digital-services@dia.govt.nz

Turnbull Up Close online

Our Turnbull Up Close sessions are usually held onsite and give a small group of people the chance to get a special up close introduction to some of the Library’s wonderful collections. COVID restrictions mean this isn’t possible this month, but instead we have an opportunity to take a closer look at part of the Library’s extensive collection of maps, online, with Curator Igor Drecki.

New Zealand Government maps

The collection of New Zealand government maps, collaboratively digitised by the National Library of New Zealand and the University of Auckland, provides a unique insight into the New Zealand cartographic heritage.

These authoritative maps of the country’s natural and social environment, together with maps of the South Pacific nations and Antarctica, have been produced by the Department of Lands and Survey (later called Department of Survey and Land Information, and recently Land Information New Zealand) since the 1870s. They cover a wide range of themes, from general, topographic and miscellaneous to aeronautical, mosaic and cadastral maps. The government also produced maps and charts for military and defence purposes.

Maps reveal fascinating stories

These maps reveal fascinating stories concerning land development, landscape changes, social trends and cultural events. They provide evidence of technological shift in map production, as well as in the advancement of cartography.

They tell human stories of the struggle for recognition and the pursuit of excellence. They are testimony to hundreds, possibly thousands of people that invested their talents and dedication to create them.

This visual tour of New Zealand government maps will provide you with the opportunity to discover them in a new light and appreciate the creative beauty of cartography

RSVP for a link to join this talk

This event will be delivered using Zoom. You do not need to install the software in order to attend, you can opt to instead run zoom from your browser.

Email us if you’d like to join this talk. We will send you a link to use on the day. Email ATLOutreach@dia.govt.nz

About the speaker

Igor Drecki is Curator, Cartographic and Geospatial Collections at the Alexander Turnbull Library. Trained as a professional cartographer, he has worked in the private, local government and academic sectors before joining the Library. Cartography and maps have always been at heart of his professional pursuits.

Map titled Dominion of New Zealand with its dependencies (and Western Samoa), 1929