- Events

- Early printing in the Pacific Islands

Early printing in the Pacific Islands

Part of Connecting to collections 2023 series

Video | 59 mins

Event recorded on Tuesday 21 March 2023

This talk by Suliana Vea, Geraldine Warren and Anthony Tedeschi will explore the history of printing in the Pacific region. They will delve into the Turnbull Library’s rich holdings and show some of the earliest printed texts, with a special focus on the use of tapa as a printing substrate.

Transcript — Early printing in the Pacific Islands

Speakers

Lynette Shum, Anna Vea, Suliana Vea, Geraldine Warren and Anthony Tedeschi

Mihi and acknowledgements

Lynette Shum: Welcome to our Connecting to Collections online from the Alexander Turnbull Library. Ko Lynette Shum ahau. I'm with the Alexander Turnbull Library's Outreach Services team. And I'm delighted you've joined us today to learn more about early Pacific printing. With our presenters, Anthony Tedeschi, Suliana Vea, and Geraldine Warren. But first, a little housekeeping.

As you'll see when you join the webinar, we are recording it. And as this is a webinar, your videos and microphones are turned off. However, there's still an opportunity to interact with those of us in the room and with others in the audience. If you would like to share where you join us from, have any general questions or comments, then please add them to the chat. If you have any questions for our presenters, any of them, then please add those to Q&A. You'll find both buttons at the bottom of your Zoom screen. We will be monitoring chat and Q&A. At the end of the presentation, I will come back to ask the presenters any questions we receive.

We will also be adding links to chat during the presentation. If you want to save those links, click on the ellipsis, that is the three little dots beside the chat button and select Save Chat.

I'll now hand over to Anna Vea, mother of Suliana Vea, the Alexander Turnbull Library Research Librarian Pacific for our karakia before Suliana gives us a brief introduction to today's session. Thank you, Anna.

Anna Vea: Thank you, tau lotu.

E ‘Otua mafimafi ko koe ko emau Tamai fakahevani ae ‘Afiona

E ‘Otua ‘oku mau fakamalo kiate koe i he aho lelei kuo ke foaki mai, ke mau ma’u he aho koeni.

‘Otua ‘oku mau hanga hake kiate koe, ‘Otua akinaulotu kotoa pe oku nau kau ki he polokalama koeni.

Tapuekina akinautolu e ‘Otua, ‘omi ha ngaahi fakakaukau ‘oku taau mo fe’unga ke fekumi ki he anga oe mo’ui mo e ngaue ki he mau ki’i Otumotu Pasifiki.

‘Otua tapuekina fakafo’ituitui akinautolu koe’uhi ke nau lea’aki ha ngaahi fakakaukau oku taau mo fe’unga moe ngaue.

Kau mai koe ‘Eiki iate kimautolu hono kotoa pe, pea ke tapuaki mai.

Kole katoa ae ngaahi malohi ni i’he huafa ae Tamai moe ‘Alo moe Laumalie Ma’onioni,

‘Emeni.

Materials that we have in our collections

Suliana Vea: ‘Emeni. Kia ora, Mālō e lelei everyone. My name is Suliana Vea and for this talk, we just wanted to raise awareness of the materials that we have in our collections. They are available for everyone to view. You just have to go through our the little registration process and you have to come on-site for the majority of materials to view them. Unless they have been digitised. But yeah we just wanted to inform you guys of what we do have, and also let you know that we welcome enquiries.

You can go to our homepage and put your enquiry through Ask a Librarian. So Anthony, he will be talking about — sorry, Geraldine will be starting us today. So she'll be talking about the early missionaries in the Pacific. And then we'll have Anthony who will be talking about some of examples of early printing in the Pacific that we have in our collections, and then I'll just be talking about Tapa and a few items that we have that are printed on Tapa. So, I'll give it to you Geraldine.

Background and historical context

Geraldine Warren: Ngā mihi, Suliana.

Kia ora, Tēnā koutou katoa. Ko Geraldine Warren ahau. Ko Ngāti Porou, Ko Ngāti Kahungunu. Ko Ngāti Maniapoto ōku iwi. Nō Aotearoa ahau. Ko tāku tūranga he Kairupi nō Aotearoa me te Moana nui a Kiwa. (I am the New Zealand and Pacific Curator).

So this is a brief introduction and, next slide, please. Okay.

So Christianity was said to have been introduced to the Pacific Islands by missionaries. And in particular, Protestant missionaries within the South Pacific were the norm. Protestant missionaries were British and American, and Roman Catholics were mainly French. And in this slide here, it's an unknown artist who's done a sketch of well, who came to be known as Queen of Tahiti in Māori, Queen Pōmare IV.

And, as I've put in the notes, Christianity started in Tahiti and moved from the East to the West. And you see in this image. From my understanding of it, it shows the queen and her husband in a full dress or formal dress. And the next two images are in their walking outfits, and the figure in pink is their son. And as you can see, they seem to have adopted-- and it's European dress. The date of this image is 1847. And Christianity was taken to Tahiti by the London Missionary Society in 1797, so fairly early.

And London Missionary Society, of course, were British evangelists. And my interest in this image is trying to understand the role of the ordinary person within supporting their monarch, or their rulers, or the missionary themselves. They seem to be the hidden figures or the untold stories, and one of the gaps within the Alexander Turnbull Library. And for me, Patiti was the high priest of Oro on Moorea — information about that. Next slide, please.

So when I've been looking through our records, we seem to have information mainly on the British figures. The European figures, like this gentleman here, this is quite well-known. But as I said, my interest is — I was intrigued by what missionaries brought to the Pacific and their responses to it. Like this gentleman became an advisor to Queen Pōmare IV.

And as you can see, he got into I guess a dispute over Christian theory and asked the Queen to deport French Catholic missionaries, which lead on to the French intervention, and so on. But I still am looking for the background information on who supported those missionaries and things like that. Next slide, please. OK. And from Tahiti, Maohi and others, also move through to Tonga. And with Tonga itself in 1822, the Wesleyan mission was established.

And then 1827, as in the notes, and please excuse my pronunciation, Taufa'ahau Tupou of Ha'apai and Vava'u converted. And he, along with other Chiefs was one of the more influential converts. And in time with the assistance of the Wesleyan Mission was to eventually became Tupou, the first king of Tonga. And again, my interest is who are those other Chiefs in their stories because behind the missionaries is the story of, I guess, connections. But again, those unknown figures. Next slide, please.

And I came across this image and only this image. I couldn't find any information on Reverend Pita Vi. The title calls them the first Wesleyan Native Minister. And I have not been able to find anything else within our collection besides this image. And within the information within the Library that I've come across, it gives other names like this. And I won't try to say them, but again, my interest has always spiked by these things. And you'll see by his dress and also by that of the King in the first image, how they've adapted the European dress.

Because of connections to power and also with Christianity became literacy — books, printing presses. Next slide, please. OK. And as I said, in 1822 Wesleyan missions were established. And the Wesleyan mission was based in Australia. And in 1885 there was a division between King Tupou and the Reverend Shirley Baker and Moulton. And I've just put little notes in there to remind me of the different, I guess, interests that were at play.

And I believe this house behind him belonged to the King. And an interesting time within Tongan history had brought to play by two Europeans who were influential in education, and printing, and literacy. Next image, please. And one of the things that stuck out to me was the religious war that started between the Wesleyans between Moulton and Baker. And that there was reports of an attempted assassination on the Reverend Shirley Baker.

And this was between the same denomination, between two Europeans. I believe that King Tupou I established his own free church with the power base in Tonga. And Moulton, the power rested with the Australian Wesleyan Church. So this is from Papers Past. You can view this online, the report of — there are many reports in there of the assassination attempt, so feel free to go take a look at them. Next slide. Because I believe from Tonga Lotu 'i Tonga was taken to Samoa.

And that was by many Tongan and Samoan converts using earlier links and not just by Europeans. And I came across this image within the Turnbull collections, and I found it very fascinating. A beautiful image and it talks about his Rarotongan wife. And in my notes here London Missionary Society brought from Raiatea, Huahine, Borabora and Aitutaki, early converts. I wondered if he was one of them, things like that. Of course, I don't know. I'm sure there are experts out there who can tell me and correct me and what things I present today. I'll be fascinated to hear from you.

And also down there in my quick studies, I came across a record that said that the King — sorry, Malietoa Laupepa threw Pita Vi into the harbour to test his faith. He survived and returned to shore. And Pita Vi, as you recall, was about two or three slides back. So, next slide, please. And the Reverend John Williams again, much of our information is around these European figures. And he was at the London Missionary Society.

And again, these names I came across, I couldn't find them in our collections. There are gaps, particularly in Pacific people. And even just knowing what to call them because it doesn't seem to be clear what positions, what acknowledgment was given to them in their time. So I believe that is the last slide that I have, and I will just introduce Anthony Tedeschi. Anthony has been with the Turnbull as the Curator of Rare Books and Fine Printing since 2015.

He holds advanced degrees in English literature and Library Science with the specialisation in rare books librarianship and has published on various aspects of book history. So I'll just turn over to Anthony. Kia ora.

Original examples of early printing in the Pacific

Anthony Tedeschi: Ngā mihi nui, Geraldine, for that. And welcome everybody to the session. Yes, so I have the honour to show some of the original examples of early printing in the Pacific for my section of the talk. And just to put it into a broader context — if we look at printing in the wider Pacific region, it dates back to the sixth or seventh century CE in China. And then printing had developed — brought again by missionaries into Mexico, and Peru, and the Philippines by the 16th century.

And then the nearest to our region shall we say, Australasia, was the printing press that set up in Australia in 1795. And their first fruits of that press, what was printed in 1802. But it was later in the 19th century that the first presses arrived in Melanesia, Micronesia, and in Polynesia through the missionaries that Geraldine has described. And so what I'm going to show are some of the earliest examples I could find from different Pacific Islands in the region.

And it's worth bearing in mind there is earlier material in the collection in different Pacific Island languages. But they were, as they were printed mainly in the United Kingdom and in Australia. I've excluded those and we're just focusing on local efforts in printing. So next slide, please.

So many of the examples that I'll show came from the collection of the library's founder, Alexander Horsburgh Turnbull. There he is as a rather dashing 23-year-old.

Turnbull joined the Polynesian Society in 1893. And I suspect it was most likely around that time that encouraged or interest in collecting in the broader Pacific and not just New Zealand material in his European interests. But in widening his net, casting his net to collecting material printed in different Pacific Islands around that same time. And his sources, as you can see on screen, he would contact missionary societies for material.

He would discuss or trade material with other private collectors such as Thomas Morland Hocken, Dr Hocken in Dunedin. And he had a vast network of international book dealers from upon which he would draw. Mainly in France for his Pacific language material, either dealers in France or a French dealer in London named Dulao that he bought from quite extensively in Pacific Island material. And you can see the collection today. Turnbull lay the foundation, has grown to over 780 books from the 19th century alone.

Now, that number is an estimate just based on my sort of searching around the catalogue, limiting it to the 19th century and to different Pacific Island languages and coming up with a total number of records. So it's likely there is definitely more than that. And that's just printed material. Now, the output of the presses since they're all founded by missionary societies, as you would expect, would be primarily religious, administrative, or for the purposes of language study and education. So spelling sheets and grammars and such.

Now, many of these books or perhaps all of them have not been examined or described in a great detail. So this is my first time seeing many of them, which was fantastic. So what I tried to do was add in some interesting aspects about these specific copies mainly from what I could find from about the previous owners, where there is evidence for that. Next slide, please.

So there's a slight delay on my end with the slides being changed. So that would be just a moment. There we go. Great. Thanks Lynette.

So as Geraldine noted, the first missionaries to arrive in the South Pacific, the London Missionary Society in the late 18th century. So they were also the first ones to bring in the first printing press into the South Pacific region, establishing it in 1817 — oh, one moment. There we are. Apologies, the light's on a timer.

In 1817 and now the press was initially destined to go straight to Tahiti, the island of Tahiti, but the missionaries stopped along the way and set up the island or set up the press in the island of Mo'orea much to King Pōmare's annoyance.

I think he wanted to come straight out, but he and his retinue travelled to Mo'orea and he had a go at printing. According to the missionary's account, he tried his hand at setting some type and pulling the printing press and printing off a small sheet to see how the technology works. Eventually, the press was set up in a Huahine that you see there. And this is the earliest example in the collection of printing in the South Pacific, is this English language report printed in December of 1819 describing the establishment of the mission at Huahine.

And naming the different missionaries who were involved in its founding. Some of whom were no longer present on the island, including Lancelot Threlkeld, who had gone back to Raiatea. And we can see in the horizontal image, it says Mr. Threlkeld and Raiatea below. So this copy had been folded up and then posted to Threlkeld, so he had a copy with him. Next slide, please. So these two examples are the earliest examples printed in the Tahitian dialect in the collection.

So the first is you can see a copy of the Gospel of Matthew. These were both printed at the Winward Mission Press in Burder's point. And that first one was done by William Ellis, his in 1819, and then reprinted in 2,900 copies, I think, the following year. And the Gospel of John from 1821, that was a translation done by the missionary Henry Knot in conjunction with King Pōmare II who helped provide the translation work.

And as you can see, that copy is noted as being bound with a grammar of the Tahitian dialect printed in Tahiti in 1823. And that is the first printed grammar of the Tahitian language to be published, undertaken by John Davies. Next slide, please.

Moving to Hawaii in the 1820s, you see the first press was established there in 1822 by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. And again, the earliest example we have of printing in Hawaii is another English language text, which is called The Good Devised printed in Oahu in 1824.

And it's essentially an attempt by the missionaries to curtail drinking by the various sailors who were calling into port, a call for temperance. How successful that was, others can possibly comment. In terms of the Hawaiian language printing, the other example, the scripture lessons that you see on the right, printed in 1825, is the earliest example we have in the collection of printing in a Hawaiian dialect. Those were both done by Elisha Loomis, I think. And then next slide, please.

This volume of hymns in Hawaiian, most likely printed by Stephen Shepherd in 1828, this collection of hymns. And in addition to Mr J Hill who we see his inscription is at the top of the title page, dated around 1831, is this present is this Germanic bookplate. And this German inscription that you can see at the centre of your screen. And I've been able to identify the inscriber, Hans Conon von der Gabelentz, who was a noted linguist in Germany in the 19th century who did a lot of work translating between Mandarin and other Chinese languages, into German and out.

And the inscription reads that his wife, his frau, picked up this book in 1853 in Leipzig and then brought it to him as a gift. And I just wanted to show this as a great example of the wanderings of books. So we have a book printed in Hawaii in 1828 and winds up in an English collection, presumably of Mr Hill in 1831. Twenty years later or so it finds itself in Leipzig in Germany bought by Gabelentz and then remained in his collection until it was dispersed somehow. And then wound up in Turnbull's library back in the Pacific in New Zealand. Next slide, please.

So these are two examples of printing on the island of Tonga established in 1831 by William Woon would have been the printer of these two texts. And the one on the left, as you can see, is scripture lessons, perhaps the first book printed in Tonga. And I couldn't find any other examples of this book having survived, but it's quite possible it's out there. If other institutions are watching, and you have a copy, please do let me know. I'd like to hear more about them.

And the other book printed the following year are these selections from Genesis, but what I'd like to do is Suliana and I were looking through the slides last week and these resonated with her in particular. So I wonder if Suliana, if you'd like to comment on the scripture lessons, and just that moment of seeing them.

Suliana Vea: Thanks, Anthony. So yeah, me and Anthony we're going through the slides last week and I was so surprised to see this book, Koe fehu'i moe tala. Koe tohhi eni kihe Otua, the first one. So, I remember, like when we were in Sunday school. And they used to ask that at Sunday school and also at my mom's church, Sunday school and white Sunday. And the kids — you're little, you're probably like under five, and you get asked these questions — they ask you in here.

So it says like, the first question was like, "Kohai naa ne gaohi koe?" And that means who made you. So they'll ask you that. And then the little kid will be like, "Koe otua" — the Lord. And then they'll ask again, "Koeha ae Otua?" which it says here is like "Koe Laumalie lahi" or whatever. But not to take up all the time, but yeah, I was really surprised to see that this existed from so long ago, from the 1800s and it's still in use now.

It's still in use today. And I was asking my mum about it. I was like, how did you guys like — where do these questions come from? She said it was just in there like lessons. It was in their Sunday school lessons and I was also part of their tests as well. So I was telling her, you know like that's from 1830, that's from a long time ago you guys still use it in church like still now. Like they're in the Methodist church, the old Wesleyan Methodist Church. But yeah, so that was like really buzzy to see this because I don't know where it came from.

I just always heard it and it's always been asked to kids and they're always answering the question, so it was awesome to see where it originally came from. And it's still used today. Thanks, Anthony.

Anthony Tedeschi: Well, thanks, Suliana. That's fantastic. You have to bring your Mum in to have a look at these in person sometime. We can easily get them out for her. Next slide, please.

So here, we're looking at two books in the Fijian dialect. Now, you'll notice that the first press was established in Fiji in 1839. And these texts date to 1838 and were printed in Tonga. Now, this seemed to be quite common from what I can find, is printing in one specific island where a press has already been established and set up in different Pacific languages for those books to be sent out until a press was established there.

To engage with the community and with the missionaries who are already there. And so this is a — you can see a four-page language primer bound with the Gospel of Matthew printed in Vava'u in 1838. And there's more to say about this copy. Next slide, please. Just waiting for the next — there it is. So don't adjust your screen. The images are correct. So what that is, is the previous book we just saw, is bound in these blue paper wrappers and pasted to the other side of those wrappers, are these fragments of printing, again, in the Fijian dialect.

And so they were just as a fragment being used as the binding. And if you have a look at the text and the imprint details, you can see it's a catechism and hymn book printed in 1836. This is a fragment of the first book printed in a Fijian language. Why it was used in this manner, it could have been the printing was incorrect, or faulty, or a test print. And so they just recycled the paper, which would have been rather scarce, into this binding material. So there's a nice little discovery, the use and re-use of previous material. Next slide, please.

So much like this example here, this collection of sermons from 1850 printed in Fiji this time not in Tonga. And that's the binding on it, which is cloth and it looks to be most likely a dress fabric. If anyone wants to comment on that, that'd be fantastic. We do have examples in the collection elsewhere of the wives of some of the missionaries donating material from their dresses or other fabrics to create the binding of the book. And this could possibly be what happened here.

It would be great to have that captured and to know of other examples of fabric bindings in the Pacific region in other collections. In terms of John Inglis, I'm not entirely sure who he is. There was a missionary who came from Scotland and settled in New Zealand named John Inglis, who was involved in cross-Polynesian matters. But so maybe him or I also found the newspaper article of an Australian named John Inglis who moved to Fiji and wrote about his life there. So it could be him, so more work to be done. Next slide, please.

So we're moving on to Samoa here. First press established 1839. And of what we can see, the book on the left is an example of the first book to be printed in Samoa, which is a comparison of different religions, Christian religions, and they printed about 5,000 copies of it. And what essentially it was, was a sectarian piece of propaganda, right. So the London Missionary Society essentially used this to attack Catholics and Catholicism as a way to prevent papists or French or Catholic French missionaries from coming into Samoa.

And also as an attempt to find a rallying point for the different Christian Protestant denomination converts. It didn't go down very well with many people, as you could imagine. They thought it was great, not so much broadly. And so for the second book printed in Samoa is this short, 16-page spelling book for children printed in 1839 as well. And they printed about 6,000 copies. And the numbers really interesting in terms of how much they were printing. You think 6,000 copies, the number of pages included, the amount of paper for testing.

It's quite an intensive process. And given you have to transport this material most likely from England. Next slide, please. Now, this is the Library's copy of O LE SULU SAMOA or the Samoan torch, the first periodical to be published in Samoa. And you'll notice a link — sorry, go back to the slide, please. Thank you. You'll notice I added a link to Auckland Museum. So really, I'm not going to say much more about it. But I will encourage everyone watching to go to Auckland Museum and look at the blog post about this publication.

It's fantastic. It's the best resource that I've read. Really insightful. I've noted the names of the blog contributors there. And so if anybody from Auckland museum is watching, kudos to you for the fantastic work you're doing with your Pacific language material. Next slide, please. And so this is an example that hearkens back to what Geraldine was saying about trying to uncover the unknown or the names of people who worked on it. So the Samoan presses, we know that Blair, the missionary printer.

He trained some local Samoans in the art of printing and in typesetting. And so they were likely involved in the production of the Samoan Torch and other periodicals and publications. Here in the Caroline Islands, the initial missionaries had trouble with their printing press. And so they brought in a printer from Hawaii. And we see him named there, Simeon Kanakaole, who was there for one year, printed three books, Turnbull holds two of the three, before he really missed his family and then returned to Hawaii.

But it's fantastic we have his name and we know a little bit of information about him, but not too much. So if anybody does have more information about Simeon again, I'd like to know more about him and his life and perhaps his printing in Hawaii if he was involved in it there. And then the last slide for me is this short, little spelling sheet. Now, we were supposed to give this talk last year, but unfortunately, we had to postpone. And that would have been during Kiribas language week.

So this would have been the first slide I wanted to show, but I didn't want to leave it out from this presentation. And you can imagine perhaps not many of these survive, given the very ephemeral nature. And you can also see that was printed in Ponape as well. And then transported and shipped to Kiribas. So that's just a quick overview, a snippet as it were, of some of the examples of early printing we have in the collection. And as Suliana noted, these are all available for scholars or anyone just generally interested to come in and have a look.

So then I will just hand over back to Suliana to talk about printing on tapa as a substrate. So over to you, Suliana. Malo.

Printing on tapa as a substrate

Suliana Vea: Malo aupito, Anthony. Malo e lelei. My name is Suliana Vea. I am the Research Librarian Pacific at the Alexander Turnbull Library. I work in the Research Enquiries team. So please, I am not an expert on Tapa and this is just all general information. I hope this will just inspire you to go and do more research yourself into what's out there and the whole process of Tapa. So yeah. I'll just start my talk. So next slide, please.

So Tapa. Tapa is known as bark cloth in the Pacific. It's known as Kapa in Hawaii, Siapo in Samoa, Hiapo in Niue, Ngato in Tonga, and Masi in Fiji. So each island had their own distinctive designs, colors, and patterns. But I think Hawaii had the most — they had the most variety. They had way more designs. I don't have images of that, but this is just to give you an outlook of what is out there. So yeah. The first image is Hiapo from Niue, which is held at Te Papa.

And then the second image is Kapa from — so it's Hawaiian, it's from the 1770s, and it's held at Te Papa as well in the Te Papa collection. So next slide, please. So Tapa is made out of the inner bark of certain trees, the most common being the Paper Mulberry, which is also known as the Aute plant here in New Zealand. Originates from — some sources were saying Southeast Asia and some would just say East Asia, so originates from Asia. And it is said to have been brought over from the La Pita people and that's up into the Pacific.

Because it's not natural. It doesn't grow there naturally in the Pacific. So there are other varieties of Tapa. They were made from breadfruit trees and banyan or wild fig. So these are just images of the paper mulberry on trees, and then the image of breadfruit. So breadfruit is a common — we usually eat that in the Pacific, especially Tonga. We love it. People like me. Next slide, please. So it's said that the origin of the word Tapa comes from Samoa. So in regards to the uncoloured border of the bark cloth sheet.

So if you can see this image here and then you can see the outside border, how it's white, although some of it's tattered. It comes from — that's where the background, the border of it. But when that's done, when it's all made together it's known as Siapo. So Kapa in Hawaiian also means edge, border, or boundary, which is similar to other definitions in the Pacific. In Tonga it also means the same thing. We call it tapa. So it's said there the term tapa was popularized in the early 19th century with European contact.

And it is also used worldwide now for bark cloth. Next slide, please, Lynette. So there's a whole process that goes into making Tapa and I don't have the time to go through that. I just wanted to show you these images. It does involve stripping the bark off the tree and then beating, which you can see in these images, the ladies are beating the bark and spreading it. But next slide, please, Lynette. These are links that I thought I'll just put in there for you guys, that are a good visual or good, was this blog that I came across, which gives step-by-step and shows the images.

Even though it's about making Tapa in Tonga, it's the last link that's on this page here. Coconet also has a lot of videos on there and talks about Siapo in Samoa and also making Masi in Fiji. I thought I'll just put in two links here in regards to — because Niue they are no longer making Tapa. And so there's an artist, Cora-Allan Wickliffe, which I thought she was trying to make Hiapo. And so she started that — she's trying to start back up that tradition.

And also here in New Zealand, there's Nikau Hinden a few years back. She started trying to revitalise making Tapa here in New Zealand as well. Because you'll see that they went out and they started just going into making using flax. So and I think the plant couldn't also grow here in the New Zealand conditions. So feel free to go have a look. Go on YouTube. There's heaps of information out there for the whole process. And it's usually done — in this image, you can see a group of women or in a group. It's done in a group.

So yeah. A lot of people, a lot of hands go into making Tapa. So next slide, please. So there are various uses of Tapa in the Pacific. The most common one was clothing. And each island had its own distinctive — like in Tahiti it was said that if you wearing Tapa, it would show that you were upper class. And then the type of Tapa, and I think they dyed it as well. I couldn't find an image, though. We're just going to use this image that we have here.

So this is a woman in Samoa. This is her wearing a dress made out of Tapa. Next image, please. And this is also our people, Samoan men in Apia when they met Guy Powles who was a High Commissioner from New Zealand there at the time and their attire wearing Tapa. Next, please. So it's also used as masks, to make masks over in Papua New Guinea. And also in Rarotonga in Malaya. We can go to next slide. It's also made of--

We used them in Tonga. We make crafts out of them. We have fans, bags. Next slide, please. As you can see here, this is an image from 1909 in Fiji. And it was used as a hanging on the walls in the background in this house. Next image, please. And so more images of men and their Masi. This was for a ceremony for I think, Ratu. I'll have to go back and look into that. Next image, please. And then we use Tapa hard out in Tonga.

Honestly, it's like everywhere. It's decorated on the walls. It's used to walk on, weddings, funerals, to sleep on. Oh, I forgot. Sorry, when I was at the bedding. So we use it as — you can sleep on it. It was also used as blankets. I remember when we used to go to Tonga, and my mom used to say that because they didn't have mink blankets and stuff back then, they used Tata Mato as their blankets. She said it was really, really warm. But yeah, it's used for all sorts of things in the Pacific.

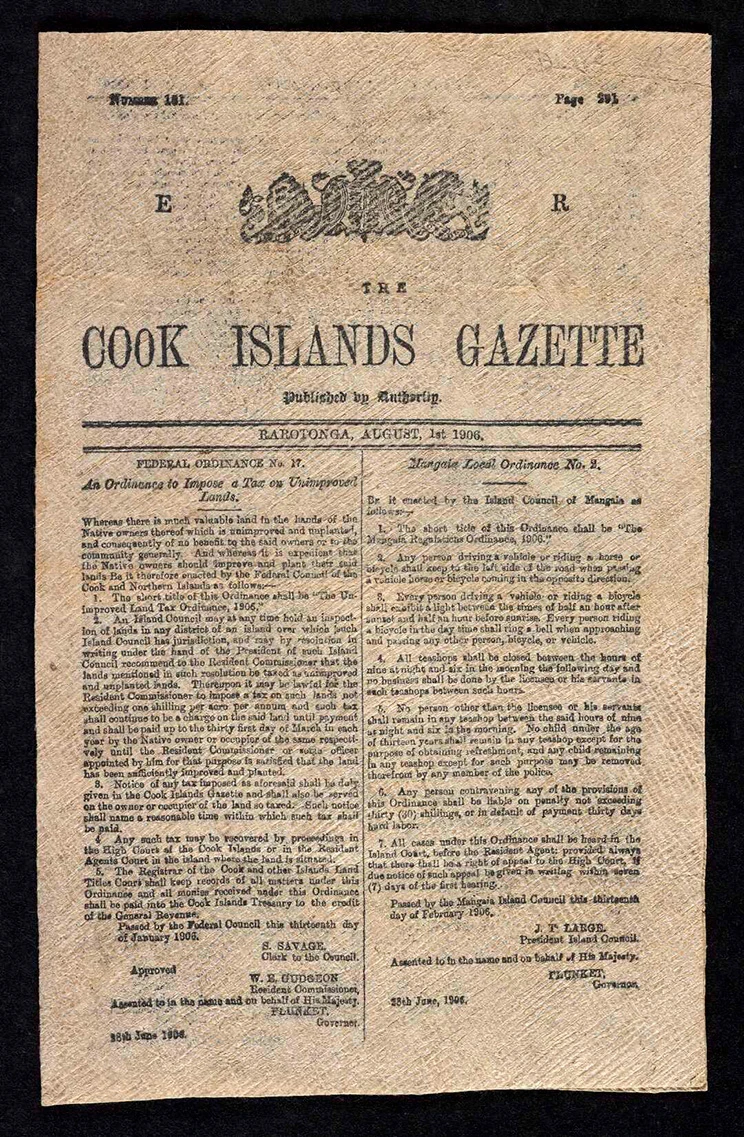

And as you can see here in this image, this is when Queen Elizabeth arrived visiting Tonga. And they put up a carpet. And so it's all — it comes in different sizes, depending on the use as well. So let's go to the next slide, please Lynette. So we have, I want to say three different serials that are printed on Tapa. I'll talk about the Samoa Times Extraordinary one at the end. But next slide, please. So we have the Cook Islands Gazette. So this is just like a pamphlet, but it's almost A4 size.

Just like close, open. This was printed in 1906 Raratonga. Printed by Stephen Savage on the government printer. And this is one of our rare book items. You're welcome to come in and view it. It's in English and Cook Islands Māori. Can you go to the next slide, please Lynette. So this is just an example. So one side is in English. And then the other side is in Rarotongan. So next slide, please. So we also have the Te Torea, which is a publication by the Catholic Church in Raratonga.

So this was a special item, it was a Christmas supplement from Saturday, December 21, 1895. And yeah this is the same size, just a bit bigger A4 size-wise. As you can see, it's torn at the bottom. And it is in both English and Rarotongan. If you can go to the next slide, please. We don't have a complete set of this in our collection. We only have a few, but I know with Auckland War Memorial Museum, they have a more complete set over there.

With this publication, they were asking when we had a trip to the Cook Islands last year and the librarian there was asking us about if were going to digitise or give them copies of this publication. But I told her, we didn't have the full set. And so contact Auckland War Memorial Museum. But we are — it is on our list to be of the items to be digitised on Papers Past. So yeah. Next slide, please. So the Fiji Times. This issue is from Saturday, January 23, 1892.

This is really big. I was surprised at the size of this item. So it says there it's 47 centimetres by 71. It's all in English. I just wanted to zoom up, so you can see how it looks on the images or how it looks like Tapa from what we think is Tapa, because I want to talk about compared to the other — to the Samoa Extraordinary item after. So next slide, please. So you can see at the top a bit has been cut out. And what we receive in the collections is just that's how it is. So we've received it that way.

Sorry, I forgot to cut my comments over there about the complete set with Auckland War Memorial Museum. So just ignore that. But we have the Fiji Times. The majority of it is on microfilm in the reading room. So it's open for anyone to access if they come on-site. So next slide, please. We have another Fiji Times that is also on Tapa. This one's lighter, really, really light in colour. And this was said to be a special edition from midnight Saturday, April 21, 1906. And was published in Fiji by George L. Griffiths and John B. Hobson.

And again, it's another mix of — it's a way bigger size compared to the Te Torea in the Cook Islands Gazette that we showed before. And again, this is all in English as well. So next slide, please. That's just the back of it. Next slide, please. So now we come to this item. When we received this item, it was sheets of [INAUDIBLE] Tapa. So I got — I looked at it, and I was like, no, this doesn't look like Tapa from what I know from my experience of Ngatu because we have it at home.

So I got Ulu, one of my colleagues, one of my Samoan colleagues. I was like, they're now going to come out for us to have a look at it. And he was like yeah, no, yeah. So we both didn't think it was Tapa. So I asked our Conservations team to have a look at it. And if you just go to the next slide, please, Lynnette. So these are just some of the comments that we got from our conversation. So he was saying that it's probably paper, but it's made with the same bark material as Tapa probably mulberry bark, which is what they use for Japanese repair tissue.

But he said they had a look at it through the lightbox and the fibres were more popped and uniform, which was what me and Ulu thought because we're like, this is way too refined. It's like normal paper, for it to be Tapa. And because we couldn't see like with Tapa, you can see how it crosses over, the weaving or the stitches or whatever you call it like. You can see it, but in these images you couldn't. So yeah. So he was telling us that they had a look through it and it was more pulp and more uniform than found in a traditional hand-beaten Tapa cloth.

And we're talking about what's the difference — how can you differentiate paper and Tapa. And he was saying that both are beaten — fibres matted into a sheet. He would be surprised if these were beaten by hand. So yeah. That's probably the reason why when we received it, it was said to have been Tapa, but it doesn't look like it is Tapa from what we thought it was. Sorry, can you just go to the slide before? So yeah, this was printed — it doesn't give us much info in regards to the printer or anything.

Because this was given from someone's personal collections. And they had a number of items and newspaper things together. So yeah. It wasn't one that we just — this is one of our recent acquisitions. I think we got it like two years ago. So Wanda, I saw your comment. I'm trying to read through it, but yeah. I just thought what in — that's just an overview of what we do have on Tapa in our collections. That are serials. And yeah. I think we'll just end there. We have five more minutes. I don't know, Lynnette, if you want me to take over, or who's taking over.

Let's see. She might do it herself here. Let's see.

Pātai | Questions?

Lynette Shum: Ngā mihi, Suliana, Anthony, and Geraldine for that fascinating presentation. We do have some questions and there's just a couple of minutes for more. So please do add your inquiries to Q&A if you do have some. But I'll, first of all, ask — oh, no, it's questions. So they seem to be mostly — sorry, I have trouble doing this at the same time as the PowerPoint. So Susan Berman says if you're interested in content relating to early printing, she has a link there.

But what does it mean to have the posters or pepa printed in Rarotonga in the 1840s in Auckland Libraries heritage collections? Oh, sorry. That's not a question. So if you download the chat, you can get that information. Malo aupito, Suliana. Was there an early Tongan Wesleyan newspaper?

Was there an early Tongan Wesleyan newspaper?

Suliana Vea: I don't know. I'm not aware. Sorry. I don't know, but did you think, Anthony, we had one in our collections?

Anthony Tedeschi: I'm not sure. I don't. I'll have to just check. Yeah. Sorry.

Do you have any material from the London Missionary Society Beru printing press?

Lynette Shum: Do you have any material from the London Missionary Society Beru printing press?

Anthony Tedeschi: I couldn't find many examples. I think there were two in the collection printed in Beru. One from the 1930s and another from the 1940s, I believe, a review of the missions in the area. But those are it, just those two items from memory.

Where was Samoa Times printed? Was it a government printer or missionary press?

Lynette Shum: Fa’amolemole from Wanda, where was Samoa Times printed? Was it a government printer or missionary press?

Suliana Vea: I think Jay must have put up something in regards the Samoa Times because it's on papers past. I think he put a link in the chat, I think.

Lynette Shum: And I see people have raised their hand, but because we've disabled that function as it's a webinar, can you please put your questions into Q&A or chat. There's a question from Melanie — Anthony, does ATL hold a copy of Shaw's Tapa Cloth Book from Cook's Voyages?

Does the Alexander Turnbull Library hold a copy of Shaw's Tapa Cloth Book from Cook's Voyages?

Anthony Tedeschi: Yeah. We do. Yeah, it's from Turnbull's collection. So we do have a copy. I think a number of the specimens have been photographed and should be available through the catalogue record. I can send you the link to that.

Lynette Shum: It's very beautiful. I've seen it. Hi, Anthony. How were you able to establish the size of the print runs for some titles? For instance, the Samoan text, which had 6,000 copies. This is from Diane Woods.

How were you able to establish the size of the print runs for some titles?

Anthony Tedeschi: Hi, Di. Glad you could join us. Yeah there was a couple of books looking into printing in the Pacific specifically. And then based on missionary archives and records and correspondence where they would outline the size of the print runs for some of the books, obviously to estimate the amount of material needed and to report back to London or wherever the number of copies that were printed and distributed. I can send you an email about that as well if you'd like.

Lynette Shum: Well, that seems to be the end of the questions. So I'll invite Ana Vea to do our closing karakia. Malo Ana.

Closing blessing

Anna Vea: Mālō, tau lotu.

‘Otua oku mau fakafeta’i koe fakaosinga o e ngaue.

Fakamalo atu i he me’a kotoa pe ‘Otua.

Fai tapuekina mai ā ae toenga ‘emau fononga i he aho koeni, pea Ke kau mai.

Pea koe kelesi ae ‘Eiki ko Sisu Kalaisi moe ‘ofa oe ‘Otua koe Tamai fe’ohi moe Laumalie Ma’oni’oni ke nofo ma’u ho’o ‘ofa ‘iate kimautolu hono kotoa pe ‘o fai pe ‘o ta’engata.

‘Emeni.

Any errors with the transcript, let us know and we will fix them. Email us at digital-services@dia.govt.nz

Early Pacific texts from the Turnbull Library collection

Although printing first occurred within the broader Pacific region as early as the seventh century in China and by the sixteenth century in Mexico and Peru, it was not until the nineteenth century that the first printing presses arrived in the South Pacific Islands with the coming of various Christian missionary societies.

This talk by Turnbull Library staff members Geraldine Warren, Anthony Tedeschi and Suliana Vea will cover the arrival of some of these societies in the South Pacific as background to the establishment of the first presses in Tahiti, Tonga, Samoa and other islands.

They will then delve into the Turnbull Library’s rich holdings and show some original specimens of the earliest texts that were printed, with a special focus towards the end on the use of tapa as a printing substrate using further examples from the collections.

Register for a link to join this talk

This event will be delivered using Zoom. You do not need to install the software in order to attend, you can opt to run zoom from your browser.

Register if you’d like to join this talk and we'll send you the link to use on the day.

About the speakers

Anthony Tedeschi has been with the Turnbull as Curator Rare Books & Fine Printing since 2015. He holds advanced degrees in English Literature and Library Science, with a specialisation in rare books librarianship, and has published on various aspects of book history. He was awarded a Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Fellowship to undertake research overseas into the book-collecting practices of Alexander Turnbull, whose bequest just over 100 years ago and continuing legacy have been celebrated during ATL100.

Suliana Vea is the Research Librarian Pacific at the Alexander Turnbull Library. Born and bred in Wellington, she is of Tongan descent with ties to Ha'apai, Kolomotu'a and the West side of Tongatapu.

Geraldine Warren has been the New Zealand and Pacific Curator at the Alexander Turnbull Library since October 2021. She holds a MLIS (2008) and MCW (2019) from VUW, Wellington and was part of the Te Papa Tupu programme established by the Māori Literature Trust in 2020.

Check before you come

Due to COVID-19 some of our events can be cancelled or postponed at very short notice. Please check the website for updated information about individual events before you come.

For more general information about National Library services and exhibitions have look at our COVID-19 page.

Previous Connecting to collections talks

Have a look at some of the previous talks in the Connecting to collections series.

Connecting to collections 2021

Connecting to collections 2022

Newspaper page 'The Cook Island Gazette', 1 August 1906, printed on tapa cloth. Ref:45057771. Alexander Turnbull Library.