- Events

- E oho! Contemporary pursuit of justice for Māori

E oho! Contemporary pursuit of justice for Māori

Part of E oho! Waitangi series

Video | 1 hour 10 mins

Event recorded on Thursday 28 April 2022

Hear Māori rights defenders Annette Sykes and Tina Ngata discuss what justice campaigns look and feel like, and what recent events have rallied acts of resistance.

Transcript — E oho! Contemporary pursuit of justice for Māori — Part 1

Speakers

Annette Sykes, Tina Ngata, Paul Meredith

Opening karakia and mihi

Paul Meredith: Kia ora tātou. Ka tipu te waikoro, te wai, te wai o mure, rire rire hau, pai mārire. Ka tipu, ka pihi, ka rite, ka rau, ka hua, ka toi, toi nui, toi ora, toi matua. Whāno, whāno, haramai te toki, haumi e, hui e, tāiki e.

Ko tāku nei he mihi atu nei ki a tātou kua huihui mai nei. Huihui mai nei ki te wānanga i tēnei o ngā kaupapa, Contemporary pursuit of Māori justice. Heoi anō mihi atu ki ngā kaikōrero o te wā, mea atu ki a kōrua, Tina, Annette, tēnei rā te mihi nui ki a kōrua.

E tika ana kia whai whakaaro ki a rātou kua mene atu ki te pō. Tika ana kia whai whakaaro ki a Moana, tērā rangatira, pūkenga, mātanga, rangatira kua haere ki tua o te ārai.

E taea e tātou te aha? Atu i te maumahara ki ngā mahi nunui i oti nei i a ia me te whai i ōna tapuwae. E whakaaro tangi ki a ia, tātou kua pōhara nei, tātou te iwi Māori. Otirā ngā mate maha kei waenganui i a tātou tēnei ka tangi, tēnei ka tangi, tēnei ka tangi.

Heoi anō ko te whakatau noa ake ko rātou ko te hunga mate ki a rātou, hoki ma ki a tātou te hunga ora, tēnei rā te mihi atu ki a tātou, nā reira kia ora tātou.

Introduction

So Annette. Kia ora tātou. It's my pleasure to help facilitate this talk today and welcome our two speakers. Probably don't really need much of an introduction. Our first speaker is Annette Sykes, a well-known wahine toa, activist, human rights lawyer, Māori lawyer.

I've had the pleasure of being cross-examined by Annette a few times. It's always a great experience. Sometimes a bit scary. Heoi anō, it's been a long time fighting for Māori rights, he mihi ki a koe Annette.

And also Tina, one of our new intellectuals, a mother from the East Coast, heavily involved in advocacy for environmental, indigenous, human rights issues. I also saw you a number of times on TV around the COVID and your mahi for your community there in Te Araroa nei. So mihi nui ki a koe. So I think I'm now going to hand over to you, Annette, ask you just to speak for maybe 10 minutes.

Mihi

Annette Sykes: Kia ora e te rangatira. Kei te mihi atu ki a koutou I huihui mai nei kei raro I te maru o tenā, o te āhuatanga o te ao hurihuri nei.

Kei te mihi ki te kaimanaaki I a tātou I runga I te whakaaro hōhonu, o te āhua Māori, hei whai whakaaro mō tō tātou nei kaupapa e pā ana ki te Whakaputanga me te Tiriti, me ngā tikanga Māori. Koinā te Tiriti o tō tātou nei whenua.

Na, ka huri atu nei ki te mana whakahī o Hikurangi, tēnā koe e te tuahine, e te mareikura, i tae mai hei hoa mo te kaupapa nei. Tēnā koe, koutou mā hoki. Me whai whakaaro me whakapū I tēnei āhuatanga. Kei te mihi.

Whakataukī and Mira Szaszy

I've got 10 minutes, and trying to promote a presentation via Zoom around 40 years of activism is a bit of a challenge. But I put together a pictorial effort on my part to show you how my activism began and some of the activist pursuits that we've been involved in. I can't even say that the starting point for my activism was at university, because my first protest was with Tame Iti against the Tasman Pulp and Paper Mill effluent discharge into the Tarawera River, and I think I was about 9 at that time. But I wanted to start with this.

He tau ora te tau, he tau ngehe te tau, he tau mo te wahine. Rapua he purapura e ora ai te iwi.

The year is good, a year of well-being, a year of peace, a year for woman. It was first listening to this whakataukī -- can I go to the next slide, please-- that I was inspired by the late Dame Mira Szaszy when I was at a conference contemplating whether to go to Auckland or Victoria University. It was a Māori Leadership Conference in the 1970s when she challenged the right of men to deny the right of women to speak on university settings wānanga.

And she started challenge to those that were in attendance. That was the Māori Leadership Conference her contemporaries at the time with the late Professor Ranginui Walker and a number of other, I think, great intellectuals of that period in the 1970s and '80s. Api Mahuika was there and Koro-- about the fact that universities' cultures seemed to be developing about a patriarchal approach that was denying the need for the growth of both Māori women leadership, but the roles for us to adapt and the way we live.

And so I think one of the first activism efforts that I became part of was at Victoria University when I enrolled in my first year there with now Judge Fox and a number of other Māori women challenging when they were building Te Herenga Waka as a result of the occupation that we had lead, by the way, in our university for the-- why a kawa was being developed that would only promote young Māori male men, most of them from boarding schools of the like of Te Aute and St. Stephens to have the right to speak.

So I deliberately chose this kaupapa at the start about activism, because, I think, in most recent weeks, there's been a lot of information in the media about what happened at my dear friend's Moana Jackson tangihanga. and why a number of the woman that he had worked with over the years paid the honor to him of speaking on the marae ātea in the forefront of the blaze of media to carry forth the challenge that Dame Mira had made much, much earlier to many of us.

I think I was 17 when I first heard her raise these issues about the equality of women and the need for the adaptation of our culture. So activism, for me, has been deeply rooted, not only in challenging Pākehā pedagogies of patriarchy but also Māori practices that have followed the patriarchy without looking very clearly at matters on this issue. There are three tapu that I was brought up with, fathers spoke and children of fathers that not speak.

I can now say, just about every tangi I go to, the sons of fathers who are still alive are speaking. The second tapu was that tuakana should speak, and teina shouldn't speak. I can say that, at every forum that I go to, quite often, it's two or three cousins that are speaking and holding that setting. And it's the third tapu that has found its more difficulty for adaptation in the modern context.

And so sometimes when you're confronting these tikanga, you have to look deeply into the values that you want to assert. For Mira Szaszy, it was about equality of women, about participation. But also about ensuring the richness of the tapestry of the matauranga that Māori women possess becomes very visible in the art of whaikōrero and then the art of participation on the ātea I'm hoping that Moana, who enabled us to have that space cherished to us during this tangihanga was pleased.

I certainly was honored to watch Tina Whitcliff. I found her speech one of the most-- I think it's a historical moment the way that she brought the challenges of his life together and his Te Arawa and Ngāti Pōrou whakapapa to meet that challenge. Can I go to the next slide to identify the kind of activity that really has dominated my life and my legal practice?

Te Reo Māori Society

When I was at Victoria University, the Te Reo Māori Society had been established under the auspices of great leaders like Koro Dewes, Cathy Dewes Robert Pouwhare, Joseph Te Rito, Lee Smith, Donna Gardiner there was a whole range of them. And I think I was about five or six years past that first wave of Māori students. This was my first march. I'd never marched. I was a kind of a girly girl when I came back from— I'd been overseas for a little while. I went to summer school in Cambridge, and I came back to university. I was at the back with a paper bag over my head because I was really shy about walking down the main street of Lambton Quay not too sure what was going on.

I had Dun Mihaka and Diane Prince not far away from me, who I think should be remembered as one of the greatest activists in the way that they challenge during the courts process is the right to speak Te Reo Māori in court to the point that Dun actually had his arm broken because he refused to speak English when he was arrested. And he refused to address the judge in English. And he actually held himself to the cell bars down in mainstream Wellington Police Station at that time.

But you know, I just wanted to show that our marchers back in that early time, they weren't the kinds of numbers that we get now. But they were just ordinary folk, men and women who had a passion about things. A lot of them, like Amster Ready there in the front there, and Aunty Tere very strong advocates in the world. But if you look through it, most of them, a lot of Pākehā and Māori, working together to see something, the injustice of the denial of our languages in the same status as Pākehā being developed.

Te Reo Māori Waitangi claim

Can I the next slide, please? And this was my first case. I graduated from law school. And everybody talks about this famous case we did to get Te Reo Māori recognised as an official language. I was assisted in the case by Rawiri Rangitauira. He's the lawyer behind me. But you'll see some common faces there, Kathy, Huirangi Waikerepuru, Tom Roa, Piripi Walker, Lee Smith.

This was the rōpū that did that case. And it mobilised a nation of Māori, the Māori nation. We had, over a period of six weeks, a range of hapū and iwi travel down at their own steam to fight for that. And while living after about, I think, two years of the liberation, by the way, Waitangi tribunal was recommended to be an official language. And then the Māori Language Act eventually came into place in the 1980s.

That struggle was 15 years. I just want to say that Māori understand, we're in this for the long game, not the short game. There's many in this photo have passed on. Hirini Mead was the professor at the Māori Studies at Te Herenga Waka. But I can tell you, the powerhouse in our team was his wife, the late June Mead.

In those days, we didn't have photocopiers. We used the gestetner. And we were over at her place all the time doing our pamphlets, all part of the tools of activism. A lot of the Māori women they were the inaugural members of the Kōhanga Reo movement that has grown to what it is today. And I always like to just remind us, sometimes from the humblest beginnings, from the thinking of change, you can achieve great outcomes. Can I have the next slide, please?

Matriarchs at the front

My next involvement was at the end of my university law degree. I changed universities by this stage and gone up to Auckland. And these three women had been working together diligently to challenge land rights confiscation. I developed a very close friendship with Eva and Titewhai. I met Whina a couple of times. But the power of these three women, I think, is still reverberating in our current generations.

They're quite different personalities, quite often didn't get on with each other. But you need to be really clear that the three of them, and even Sue Nikora, who you see in the background there, those woman united the four winds I think, to challenge the land rights processes of the 1970s and '80s. And this was us and the hīkoi to Waitangi in '84 with Tainui.

We left from Huntley in the morning, and we went up to Waitangi to challenge the processes of privatisation that were happening at that stage and to try and seek significant constitutional change on the back of the fights of Ngā Tamatoa who are in the right of the photo at the back. So quite often, it was the matriarchs in the front with the rangatahi activism at the back providing the muscle as well as the strategy for many of the things that are going together.

And I think that was one of the-- I think, if you want to look at the sense of how we achieve justice, it was weaving that tapestry of skill base together, recognising the old and the young both had strategic analysis that was part of the success of our movement.

Eva Rickard and Raglan golf course

I want go to the next slide. It's taken taken at Eva's birthday just prior to she passed away.

We just had her land returned after the protests at a Māori Land Court sitting in Hamilton where, after much negotiation, her lawyer had been Dame Silvia Cartwright, right through the processes following the arrests at Raglan. But I was fortunate to be the one that finished it for her. And my friendship for Eva kept me in good stead.

But also, when the Tainui settlement was negotiated, we joined forces together with many of us to challenge Bob Mahuta and a number of others that were promoting a treaty settlement framework based on the fiscal envelope processes, which denied Māori fundamental rights of ownership to water, geothermal, seek limits and caps in terms of the amount and quantum of money that was available to us, but more fundamentally, denied the rights of Hapū to be recognised as the primary rights holders in treaty claims, substituting it with something called the Large Natural Group.

And Eva and I, I think our friendship was a good training ground for me. So any budding activist out there,find your local auntie, your local nanny. They have more skills in the way to deal with the strategies of change than anyone else.

People-- can I have the next slide-- will remember that this is more of Eva. She was actually arrested with 19 other people at the Raglan golf course. She was ostracised by her tribe.

The 19 other people arrested with her were people like Hana Jackson and Syd Jackson, and Angeline, and Roly Hubbard. They weren't the rich and famous or even the media-focused Māori of that period. I think people need to understand, quite often, those that the media attribute as being the leadership of activist groups are not those. And I just think in contemporary times, we need to be really clear when we're dealing with media that we have strategies as well.

Eva was an extraordinary woman. And she kept the heart of the nation just like Whina did. And I think this photo spoke volumes for the way she was mistreated on that occasion. And then again, as I said, 30 years later, subsequently vindicated with the return of her land that had been wrongfully taken for an aerodrome in the 1940s.

Merata Mita and Bastion Point

Can I go to the next slide? This woman here I think changed the face of how activists were perceived, largely because of the Patu squad film, which I recommend to everybody to watch. Merata Mita, who is from Te Arawa She was part of the first kind of protest group that I was part of with Hana Jackson, and Syd Jackson, and Tui Pokeopa, and Tame Iti. It was called Te Kotahitanga o Waiariki.

During my involvement with them, I was actually the babysitter. I was nowhere near the front. But Merata was controlling the media at Bastion Point. Tuhi Po and Tame were occupying Bastion Point. And Hana and Syd were also deeply involved in the establishment of Māori unions. But I think the way that the images of Bastion Point were captured, the way it went out, and the injustice that was being inflicted by the Muldoon-led government, you cannot underestimate the contribution that Merata it to made in it.

Of course, she was one of the first that developed the Māori cinematography that's actually dominating the stage worldwide with the film Utu, as well, during this period. I can go to the next slide to some of the photos that she took at Bastion Point Are the things that captured the hearts and minds. So when you're looking for purpose and struggle, that's what you have to go to.

Tariana Turia and Pākaitore

Can I go to the next slide? I moved now to one of the other main activities that we became involved with I think that also moved the nation. And that was Pākaitore , which you must recognise Dame Tariana Turia was one of the main creators of that movement who, a number of the members of the Catholic Church and the Rūnanga Whakawhaungatanga o ngā Hāhi of the country were involved.

They were very conservative leadership there, but lead by groups like Niko Tangaroa, who was a strong unionist, Ken Mair, who had previously been in the armed forces was a Navy man had returned home and others that led that Pākaitore struggle. And if I go to the next slide, my roles in these were to mobilise our people to walk. And I think for me, that was kind of another big movement that was starting to emerge.

They were becoming more localised from the trips that we'd had to Waitangi from Tainui up to Waitangi. And then we were in the middle of Whanganui in here. And again, you see, it's not the rich and famous, although Atareta Poananga is in there. It's the people that have come, mobilised because they felt the sense of injustice that had been occurred with Michael Laws, as he was the mayor of Whanganui at that time, and the denial of Pākaitore to be returned and restored to its people.

It eventually was, although I understand that the treaty settlement is still going. The power of the activism was to focus the issue to the questions of the racism that was being inflicted on the peoples of Whanganui at the time and a range of issues. I represented all of those that were arrested at this particular March. One of the key cases I was reflecting on from this was the time when Ken was arrested.

We tried to get a karakia into court. And of course, the judge denied us the right to have a karakia. He was held in contempt of court. So was I. And Ken was actually held for 21 days before he was finally released after an appeal.

Mereana Pitman, Ani Mikaere and Moana Jackson

Can I go to the next slide, please? Now, these intellectuals should not be underestimated in the way protests have developed. You may or may not recognise them. But the three I want to draw focus to is Mereana Pitman, she has to be one of the staunchest minds in the protest movement of the '70s and '80s. Ani Mikaere who rejected Pākehā academia and set up the course at Wānaga on Māori laws and philosophy and the late Dr. Moana Jackson. The other two woman in this are visiting spokesperson at the first Māori criminal justice who we had to set up our own criminal justice system. It was being hosted at the time by Ngāti Kahungunu Moana's people.

And we brought a range of people, and something like 4,000, to talk how we might reclaim tikanga Māori as the first law of this country. In any movement, you have to have an engine room. You have to have clear, decisive action.

And can I say, Moana Jackson is going to be sorely missed because he was really the conductor in the engine room for us. He was the engineer, quite often. And I don't know who's going to fill that role as we move forward.

Foreshore and seabed

But in movements with change, these are the contemporary challenges that we have to face. Can I go to the next slide? The foreshore and seabed debacle, that's Hilda Harawira’s mother in the middle there. I just can't thank the people of Te Tai Tokerau and Kahungunu enough who mobilised 60,000 Māori to march to Wellington to show the basic of our human rights by a government that deliberately legislated against what the Court of Appeal not had recognised would be our rights.

These matters, of course, were taken to the United Nations. The Special Rapporteur, Stavenhagen, and another have come back to try and rectify it. But all of us will remember that, by the stroke of a pen, our land was confiscated and through legislation.

I think it's a deep, gnawing issue for us at the moment. The protests went through every town. Here in Rotorua, we had six or seven Kapa Haka groups Te Mātārae-i-o-Rehu was one of the most noted ones.

But I just want to say, in movements, it's young and old. It's the rich and the poor. It's those that are prepared to put their bodies on the line that really make the difference, I think, in mass movement for change. Can I go to the next slide?

‘Terrorist’ raids

Everyone might remember me, I think, in this case, which was the terrorist attacks on the part of the violent state, the state terrorism that occurred to the peoples of Te Uruwera. I defended 18 of the 25 that were arrested. All of my 18 were eventually acquitted. But it was a 10-year trial. And this was one of the protests outside the courthouse in the courthouse in Rotorua.

One of the things I've got to thank the people was that the public, the Māori public never gave up. When they saw the injustice of what happened to the people of Rūātoki and Te Waimana and Maungapōhatu they mobilised. And they were outside the court, screaming for the release of all of those that were wrongfully charged. Under the Terrorist Suppression Act, they were able to be held for 21 days without charge. And during that time, there was huge pressure put on the government with marches to Wellington and to the Solicitor General's office to stop it. And those were erupting moments. These weren't planned. They were just people that cared enough to make sense of justice and to work on to do it. Can we go to the next slide?

Racism within the state

And then in more recent times, what we've been confronted is the racism and the suggestion that because we seek power as Māori to give effect to Te Tiriti principles of equality and equitable outcome that we're actually uppity in our own approach. And of course, some of the reactions to Pākaitore, to the demands for equality that have been made by Māori, the National Party and Don Brash’s speech. But they even penalise people in their own party.

Can I go to the next slide? We should remember the racism that was suffered by Dame Georgina te Heuheu, because her party decided that they wanted an old white man in charge of Māori affairs because she seemed to be too pro Māori in her speaking and support for many of the issues around the fiscal envelope that her own father-in-law was decrying. So I just want to say that when you're protesting quite often, you want to protest against the state, you also need to understand that within the state itself, there is layers of racism that are working to undermine even those that are using the system for incremental change.

And we need to recognise those as allies and to support them when they're actually being frustrated in their efforts. The last issue that I wanted to highlight, because I think it segueways into where Tina's going to take us is one of the biggest matches that we were involved. Can I go to the next slide?

Multi-agreement on investment march

Arose actually from our Waitangi discussions around the multilateral agreement on investment. For people who don't know, Hiraina Marsden is the daughter of Māori Marsden.

There, she’s the creator of — one of the three designers of the Tino Rangatiratanga flag. Can we go to the next slide?

And that mobilised us to all attend before we went on the MAI march to meet Nelson Mandela, this is a photo at Tūrangawaewae when Nelson was here with some of our Indigenous contemporaries from the Pacific who'd actually come here like Oscar Temaru, who we'd actually protested with in Tahiti against the nuclear-free independence movement, coming to join Eva, Tame and those that have fought for our matters like Hilda when Nelson arrived. We were all part of those welcoming ceremonies.

Can I go to the next slide?

And this was who was the Multi Agreement on Investment marchers. They were young women that could see that the capitalism values that were being used to exploit Papatūānuku, weren’t those things that we wish to achieve as a future for our children and our mokopuna.

Many of them are lecturing now, are artists. Many of them are already working in the space to ensure the sustainable environment that the mana o te taiao is something tangible for our future generations and looking carefully at free-trade agreements and how they are undermining our mana and sovereignty over our own land through the institution of transnational capital.

TPPA and anti-mandate protest

One of the last matches we did, if we go to the next slide, was in Auckland. You might remember, it was organised by, I think, the Green Party and the Māori movements. It was a significant protest during the signing of the TPPA that had been organised by our government. I think the issues related to free trade are still high on our concern because of the undermining of our sovereignty.

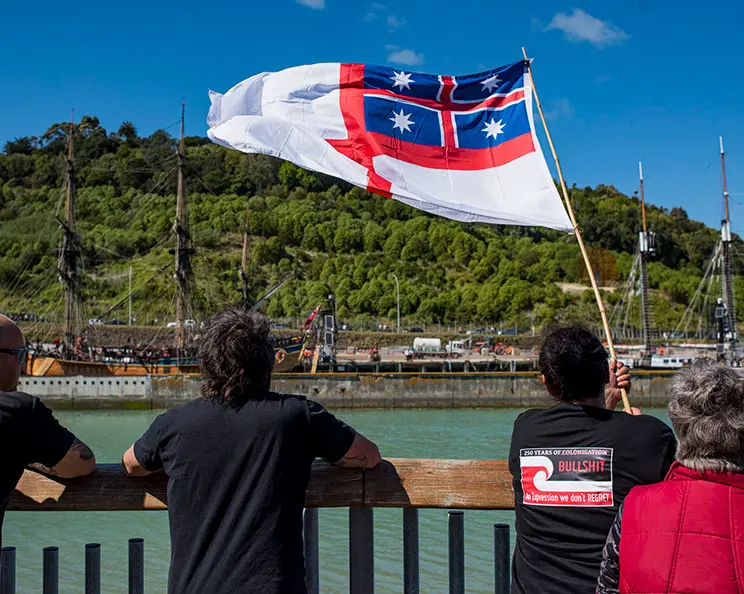

And in this march here, when we had a collaboration of a number of Pākehā, Māori, and environmental across the spectrum groups, I think it showed that there are some values that bring us together, that there are single issues that we can fight together, and we need to do this. I contrast with the kind of organisation of this movement with what happened with the anti mandate debacle that I saw happen in parliament. I mean, I saw the Tino Rangatiratanga flag flying with the Nazi flag.

I don't know if people know this. I came out of the Court of Appeal and I demanded that the Nazi flag be taken down and the Tino Rangatiratanga flag repatriated to me during the anti mandate march. You can't use our kaupapa to then try and use it as a mask to shield fundamental racism and other issues.

And I think that's one of the challenges that we face in organising protest at the moment.

And the contemporary sense is how we organise together to educate for justice and the liberation that we all seek. So I hope in that 10 minutes, I've given you a snapshot of my life, my commitment, but how in the contemporary terms, you guys have to do it.

Paul Meredith: He rawe katoa ngā kōrero. Think you have enough to write a book on it.

Annette Sykes: It's called "Holding the Line." It's in process.

Paul Meredith: Ka pai. Over to you now, Tina? Tēnā koe.

Tina Ngata: Tēnā koe Paul, ngā hau kua whakawātea te ara mo te hui nei i raro i te marumaru o te wāhi ngaro nei. Ka mihi ki a koe, ki a koutou kua karanga mai ki a māua, kia noho tahi, kia kōrero tahi e pā ana ki ngā huatanga o te wā nei, o te rā.

Ki a koe e te mareikura, e te tuakana Annette, me te mana me te rangatira o tō tū o ngā tau o ngā tekau tau kua pahure ake nei. Hei aha, hei whai tikanga, hei whai oranga mō ngā mokopuna heke iho, nei tā mihi, ngā mihi mutunga kore ki a koe.

Continuing the legacy of resistance

Really honoured and daunted to be following a kōrero of such an amazing kōrero. I could have sat and listened to that for a long time. And I guess really, I don't have this amazing legacy kōrero to share in the same way. But there's a lot of connections from what I was going to have a chat about today to what Annette just shared with us.

And I'm just going to share screens. Hopefully, that's showing now. And it's really about some of our thoughts I guess, some of my thoughts around continuing the legacy of resistance, this amazing legacy that's just been laid before us by Annette. I'll talk a little bit to some of the stuff I've been involved in but just really some reflections around that legacy.

United Nations Permanent Forum for Indigenous Issues

And I'm mindful at the moment that right now, the United Nations Permanent Forum for Indigenous Issues is on overseas. It's been on hold for two years because of COVID. And so just sending my thoughts over to all of our Indigenous brothers and sisters, and those that are representing our rights in that space, and just thinking about the work that's been put into and the amazing stances that Annette has made in that space, the formative work of people like Moana in the space, one of the architects of the Declaration for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Ngāneko Minhinnick those who have worked so hard to find that space for us to have our voice so that we can tell our own stories rather than having our stories told in that international forum by our colonial oppressors, more often than not.

So and it was in this space that I kind of stepped into. And it really came off, I guess you could say, the foreshore and seabed march because the United Nations were looking to appoint Helen Clark, or they were considering her as the Secretary General for the United Nations General Assembly. And it felt really important at the time to point out that probably our nation's largest contemporary land grab happened under the purview of Clark.

And so I felt it was important to take it into that space, take that story into that space. And when I went into that space, I was supported by Moana. And Moana had given me some kōrero to help me understand what I was going into. But also, I sat and I listened.

And there was three-minute snippets. And you had three-minute snippets of rights violations and injustices from all over the world, extreme rights violations from all over the world. And it was so heavy and so hurtful.

And I really didn't know. I could identify with a lot of it. It was very similar things that was happening to us that I saw happening in other places.

But also, there were many things just beyond the pale. And it was very heavy, a very heavy space to go into. But also, I learned in that space around the doctrine of discovery. And I had no idea. Really, I had never heard of it before, at that point.

And thankfully, at that point, we did have Moana who I could go back to go, what is this thing? Because it's in the preamble to the Declaration for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. What are they talking about with this Doctrine of Discovery?

And so I was given a masterclass, thankfully, on what the Doctrine of Discovery meant. But also I was amazed that we didn't really understand it here. But also that it was this driver, it was described as the driver of all Indigenous dispossession in Africa, in Asia, in the Americas, right around the world. It was the driver of all Indigenous dispossession.

And I thought, well, that's pretty huge. I think I need to learn about it and find out, is that the driver of Indigenous dispossession Aotearoa as well? And so these are some of the early questions that I had from engaging in this space. And I want to acknowledge that in this space, it's often misrepresented as a lot of bureaucrats.

But there are activists, there are grassroots people who fight and fundraise and sometimes hitchhike across the country to be able to go there to find their voice and place their voice in that forum. And it was a lot of work from our Indigenous leaders to be able to put that forum together for that to happen. And that's another form of a legacy also for us to respect as well.

I'm going to quickly give two-second overview of the Doctrine of Discovery so that people understand what I'm talking about there. And it's really abridged. We could spend hours talking about it. But essentially, what we are talking about when I say the Doctrine of Discovery is that we're looking at a global, imperialist regime.

Doctrine of discovery

And it was set up over 500 years ago. In fact, you can go back further to the Crusades as the beginning of these kind of papal laws that was based upon white Christian supremacy. And it set in train a series of events that led to the kings and queens, the monarchs of Europe sending out people to conquer the globe, to set up out grow their empire, to set up systems of extraction, and at some point or another, most nations around the world have been impacted by it.

They were discovered and claimed and then extracted from. And the whole thing really is an economic exercise. The full name is the Doctrine of Christian Discovery. And it's often talked about as a religious concept.

But it is, at its heart, an international, transnational economic project that has worn the cloak of religion. And it has worn the cloak of economy. It's worn many cloaks. But it's always, at its heart, been an economic project.

So it was carried out over quite a few years, fundamental to the story is the post World War II conference called the Bretton Woods conference where a lot of these nations who became rich through the system of extraction from Indigenous territories, the disposition of Indigenous peoples, and the enslavement of Black peoples, which happened at the same time as the Doctrine of Discovery and was first applied here in northwest Africa.

So it did two things. It set the context for Indigenous dispossession. And it set the context for the enslavement of Black peoples. And that continued around the world as a system of extraction and exploitation. And it was embedded into international trade and international relations and our international economy through the Bretton Woods conference of 1944.

That conference saw the founding of international institutions like the World Trade Organization, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and set up systems of loan and debt. It's still maintained poverty and third-world debt and marginalization of impoverished peoples around the world. And that still exists today.

But it also set the context for all of this, in fact. All of the, I guess you would say, tikanga, under, you know tikanga kino,under this regime, all of us set the context for modern imperialism as it appears and corporate imperialism. So corporate empires, their practices and their principles and their protocols are based upon this legacy and this history of classic imperialism.

And what we see a lot in these kind of transnational trade agreements and issues of the lowering of environmental protections and regulations, the degradation of Indigenous rights, particularly as they have pertained to the environment, all of that has its roots in the system that was set up through the Bretton Woods conference and international monetary institutions that were based upon all of this history of exploitation and extraction and creating global empires that centered all of the wealth upon the global North.

Global imperialism and the rise of the far-right

So that's just the quick, abridged version, story of the Doctrine of Discovery. Now, what does that look like today? It's taken quite a few twists and turns over time. And one of the things that's happened is that all of this amazing work, what Annette has talked about before, the blood and the sweat and the tears and the advancements of these people over time has led to social justice, the social progression.

They knelt down for the social justice. Many of them are still in power today. Many of them are in government today.

But also, quite a few of them have great economic power. And they have worked very hard to destabilise and regress the progress that has been made through this legacy of resistance. And what we see today through the insurrections and the mimicking of what we have seen over in the far right over in the US over here and the transnational spread of these ideas of supremacy and needing to dial back on progression and the denial of climate change, a lot of those things still also are a continuation of this legacy of white supremacy and imperialism as well.

And it's taken different forms. So we see it obviously and a lot of these far-right leaders here. But it's also been capitalised upon by other far-right leaders such as Modi. And it's also been capitalised upon and utilised with in Aotearoa to confuse and subvert Māori resistance movements as well. It's capitalised off the lack of trust that we have with those systems and has created a diversion and uses diversion tactics.

Annette referred to that when she talked about some of the things that we've seen with the Trump flags, and the Tino Rangatiratanga flags, and the Whakaminenga], and these references to our Mana Motuhake movement sitting alongside extreme right and even Nazi insignia as well. And so there's an extreme destabilising and deliberately confusing tactics that are used by the white supremacist and global right movement to dial back essentially and regress the social justice progress that's been made by the likes of Annette by the likes of Moana by the likes of Tame and by the likes of international movements, climate movements, international Indigenous movements as well.

And so that's a lot of what we're seeing playing out right now. And it's something that, for those of us that are coming into the space of having to carry this legacy on, we need to learn about this. We need to learn about it, because otherwise, kei te potiti haere. We will wind up getting pulled off track. And you can see it happening already that some of us are getting pulled off track by the deliberately confusing tactics of the far right. And these people are very dangerous.

But I want to point out is that this is an international movement. And they are internationally funded. They are internationally managed. They operate without borders. And they are very affluent as well. And so we need to be very aware of the transnational and international nature of the rise of the global far right and what that means when it comes to Aotearoa here as well.

And it's a real change also. Sorry, before I go on. It's a real challenge also for the Beehive. And this picture isn't just done here because of the protesters. This picture is in here because the Beehive itself, and I'm not talking about any particular party. I'm talking about the Westminster parliamentary system of Aotearoa is also a mokopuna of this story of imperialism and colonialism.

And so it's very easy to draw our people into hating on that and build a bit of a chorus of malcontent that is really there to destabilise the system and regress our journey as opposed to progressing it towards Mana Motuhake and Tino Rangatiratanga. So one of the takeaways from that story? It's that imperialism and colonialism is the root cause of global injustice. And I don't care.

I mean, unless you're one of the top 1%, you're negatively impacted by it. Pākehā mai, Māori mai, all of us are negatively impacted by this. And in fact, because it's also the root cause of climate change, there is no escaping it for anybody.

And movements like the climate change movement need to understand we're not actually going to sort this until we get to the core issue of imperialism and colonialism. You won't be solving some of these existential issues like our COVID pandemics, which are still raging on with multiple variants because these rich countries that have become rich off the back of Indigenous groups are refusing to allow for vaccines to be equitably shared to poor countries that have been made poor through this history of imperialism and colonialism.

And similar to climate change, we won't solve that until we get to the root cause of dealing with imperialism and colonialism as it appears within Trump governments and as it appears within New Zealand governments, multiple New Zealand governments as well. As I said before, the global phenomena, they're globally funded. They're globally constructed. And they exist within governments as well as within extremist organisations.

So you can't just point the finger at New Zealand's far right, some of these ones on their sideline accounts posting horrible stuff. And it's terrible stuff. And that needs to be addressed. But let's not pretend that that's the only place where this exists as well.

And in fact, the lack of movement of our government and the inability of this government to be able to act against white supremacist and far-right extremism in Aotearoa, when you compare that to how they've acted against Māori activists and Māori rights campaigners in previous years, the difference in the response of our government between those is directly connected to the fact that white supremacy also exists within our government, not just within these far-right extremist organisations.

It's connected to and it's a response, the rise and white supremacist threat and risk around us and rights campaigners and environmental rights campaigners that we're currently experiencing is directly connected to advances in social justice. And it seeks to regress social justice movement and the lack of government response, as I just said before, to the rise in white supremacist threats is also connected to the opposition in social justice. And those are inescapable truths that the government also needs to deeply consider if it wants to really tend to the issues that are in front of it right now.

How can we respond?

So for us, what are the things that we can do to respond because it's huge? Like, when I say that it's international, it's huge. It's a huge international phenomena. And it feels daunting for us to have to do it. But just like Annette said, you've got to hold the line.

And what is the line look like? Here's the line. And we've had many-- And this is one of the tactics of the far right is to confuse us around what holding the line looks like. Our line of resistance, I think that was happening in the 1920s.

And the part of the resistance of Parihaka, the peaceful resistance of Parihaka, and our land marches and the reo marches, as Annette has so beautifully laid out before us just now. And the history of Ngā Tamatoa and the marches, the history of our marches ,of our hīkoi to Waitangi and the Foreshore and Seabed March, the incredible work of Annette, and Moana, and Ngā Nikorātou katoa, and look at how that, as a legacy, needs to shape and inform our pathway going forward and how we engage internationally with this movement.

And so in connecting to global resistance movements has to come with this deep understanding of the whakapapa of resistance that we come from so that we can respectfully engage with the Black Lives Matter movement and understand that it's started in the same place of the Doctrine of Discovery and has taken different pathways. And it intersects with ours in many ways. But also to understand that you're not going to deal with climate justice until you deal with racial justice and connecting to these huge movements like the Indigenous rights movement.

There are over 500 million Indigenous peoples around the world. And we are only on one fifth of our land entitlement. They're our rightful lands.

But in that one fifth, we've been able to sequest 330 times the global CO2 emissions, just in our little bit we've been able to hold on to. So what would that look like if the LANDBACK movement actually got traction and we were able to get our Indigenous rights returned around our lands. There would be global ramifications for that.

And I guess I just want to finish on this because that really, we see the Tino Rangatiratanga flag being flown very cavalierly, I guess. I don't know if that's a word, cavalierly, in a very cavalier fashion in this last year alongside the Trump flag, which really hurt our hearts. Tino Rangatiratanga is about Mana Motuhake.It is about self determination. And don't let anybody else sway what you think. It's actually about and it is about this legacy and this history and this story.

And so I think we need to work really hard to reclaim that, to reclaim the mana, and to hold fast, to hold the line around the mana of these symbols and of these stories and telling these stories so that we can engage internationally and pursue these rights, whether it be around the table to deal with multilateral agreements or trade agreements and investment, transnational issues such as climate change and COVID and plastic pollution or all our transnational issues like white supremacy and the rise of the global right, all of these things need a transnational awareness for our movement moving forward.

And that needs to be grounded in the whakapapa of the legacy that we've come from. So I guess that was all I had to share today. But, yeah. Mae anō ki a koutou, ki a koe anō hoki Annette, mō tō mahi rangatira. Tēnā koutou.

Transcript — E oho! Contemporary pursuit of justice for Māori — Part 2

Questions

Paul Meredith: Kia ora koe e Tina. Rawe katoa ngā kōrero.

I think Annette probably gives us confidence a new generation of intellectuals. That was very, very impressive. We are going to take some questions. And so I invite you to put on the chat your questions. Just to note that anything inappropriate will haere ki waho.

So just please keep them appropriate. But yeah, so please offer those questions now. I suppose I've got a few questions. I mean, Annette, I mean, you just mentioned you started when you were nine. What keeps you motivated? Are you seeing change?

Annette Sykes: I see changes and I see regression. But you know, I had a grandmother that instilled in us that we have to fight to get things back that were taken from us wrongfully. And so she was my model. You know, Tame was at Kauwerau working at the mill and there was a mauri stone that was going to be destroyed by the diggings from Fletcher Challenge.

So when your grandmother protests and there's only six of you, anything's possible. So you asked me what drives me - It's that. I've had some hard times when they threaten to charge me with sedition because I challenged the APEC Conference as a conference that Māori would support.

When I've seen some of my best friends beaten by the-- Angeline and Eva, Eva was beaten. It's really hard. And during the fiscal envelope stuff, my children were targeted, so that personal stuff keeps you focused. But you just set up strategies, because I'm sure our tīpuna faced worse kind of challenges then in the modern context.

But the other thing is, the injustice that's happening to our people, people are getting murdered on the streets by policemen. I'm sorry, if you don't do anything, you're part of the problem. That's just the simple answer to that. And just knowing that you're not alone, quite often I've been the one holding the flag. And there's six of you.

You just think there's 4,000 ancestors and you can keep going. Otherwise but lately, it hasn't just been six of us. It's been 4,000 of us or 60,000 of us. So the movement certainly worked. And can I say, Kura Kaupapa Māori radio stations and Māori television have been a major tool in ensuring that our messages are not silenced by white propaganda.

Paul Meredith: Of course, you were there, at that court case, which was at the forefront of that and the vanguard out that. Tina, what about you? I mean, I'm thinking about the Tuia250 and your involvement there. It would have been the challenging, I suppose one of the things I suppose the challenge is that sometimes even your own people might disagree.

Tuia250

Tina Ngata: Well, I think you can take it for granted that whatever your standards, we're not a homogeneous group. And in fact, it's often cast upon us that because you're Māori, you can only be one-dimensional and must have a particular opinion. But we've always had this kind of wide spectrum of opinion within Te Ao Māori. And there will always be people who agree or who disagree with what it is that you're going to stand for.

But I think one thing is you need to understand the issue deeply. You have to wānanga it. And some of the danger that I see these days is that there isn't a real depth of wānanga around the issue from our perspective and to understand what things mean for us. So because you have to be confident to be able to-- Even if it's just you. Even if it is ever just you physically, you'll have your thousands of tīpuna by your side.

But you're mostly have them by your side if you believe in it, if you stand for it, if you really believe in it in your heart that what you're doing is the right thing and you've had careful wānanga over where you stand. I also do though. I tend to look at the people who I respect and who I know have put in the yards, who have put in the work and see where they're standing on the matters as well.

So I have always looked to well, what's Annette got to say about this? What's Hone what's Kōkā Hilda, got to say about this? What does Angeline, what does Moana, what does-- And I have a look at what-- Because they have got that experience and that background and that legacy.

Tuia250, that also came out of that first experience when it was around about then that I learned that the government was even considering holding anniversaries to celebrate Captain Cook and learning as I was about the Doctrine of Discovery, it was just such a deep re-entrenchment of colonial fiction in our world that set the context for the continuation of colonialism, which is actually what we needed to be dismantling at this time for everybody's well-being, which is why we stood there.

But that came off the back of a lot of wānanga. And I also want to acknowledge that the support, Moana was just by my side right through that. Annette was a huge support, Terenga Huia and Kōkā Robyn Kahukiwa were massive supports at that time. And so when you have support from amazing people like that, you're able to keep putting that one foot in front of the other, even when you're exhausted.

What makes a Māori protest?

Paul Meredith: We've talked a lot about those the global issues. And a lot of our movements being influenced by global movements. What makes a protest a Māori protest? Maybe if you can answer that, I think Moana used to say you're a lawyer that's a Māori, or a Māori lawyer.

Yeah, and you hear the same thing with art. Well, are you a Māori artist, or are you-- and I think Ralph Hōtere was kind of famous for his discussions around that. Or are you a Māori and an artist? And I think it's the same thing each time is that, first and foremost, it needs to be by Māori for Māori.

And you can have your allies. And we do have some amazing allies that have joined. But sitting at the center of it and leading it needs to be Māori and tikanga Māori and kaupapa Māori. So it's the tikanga and the kaupapa and the leadership of it that I think creates that definition. But I'd be keen to hear what my tuakana has to say around that.

Annette Sykes: I can't disagree with anything that's been said there. But ahi kā has a lot to do with Māori practice. You recognise who leads as those that have the mana in place.

So you come in, not over the top of them, but supporting. And you bring your skills. And certainly for me, because I'm a national advocate, I don't go into places unless I feel that I can offer them or I've been asked to. So Paul, it's recognising who has the mana, who has the mana whakahaere who has the ahi kā of the kaupapa.

But then, there are some kaupapa that change, you know, like the transnational stuff we've just heard about. Black Lives Matter, that resonated right throughout the Māori world because the kaupapa there is mana. If your mana has been attacked, there are kaupapa values that transcend, I think, domestic reality.

So you just marched up. When I went to South Africa to sit with Winnie Mandela during the World Conference against racism within Angeline. And the vitriol she was having as a woman that was maligned by the media. Just being there with her was a way of just solidarity. And then Angela Davis come up, all your heroines, all your heroes turn up.

Oh, no.

Hey, Fidel Castro then invited 90 of us to a huito go to have a listen about how to be activists. So these things just, if you have the values right, trust your gut. And trust what you do. You're no better than anyone else. But you have to be true to yourself.

What’s the role of Pākehā?

Paul Meredith: Tina touched on it a bit too around the role of Pākehā as allies. What do you think the role of Pākehā as contribution to contemporary Māori justice. I was just thinking that the TPP had a lot to do it the likes of Jane Kelsey, John Hart with the Springbok Tour. Those sort of Rangatira Pākehā.

Annette Sykes: We've got some young ones now. They're really good. And we got some Asians with Tino Rangatiratanga.

Ming Zu is on this, I see. We have got great allies who understand that kaupapa. They are there to support. They are some of the best strategists. John Minto during the Springbok tour.

When some of our people got badly done here at the Rotorua game and the Gisborne game, he didn't just go away after the practice. He came and stayed with us during the trials. They fed us, cooked for us, and maintained friendships over 30 years, and walked down mountains with us.

He loves going through , one of his biggest things. Those friendships are about common values. Tina, I think we've got some really good Pākehā intellectuals now. Max Harris, he's the Rhodes Scholar from … everywhere.

When I was doing a case, he just came out of the blue. I'd never met him. He just wrote to me and said, do you need some help?

And so he did. He helped me. And we didn't win the case. But the case became famous.

So how did Pākehā help? By offering but respecting and by not substituting our mana. But also recognising they have a fundamental role, I think, in our lives. Just as we can be allies their kaupapa. I go to a lot of what I know is kaupapa Pākehā things.

I'm right in there with them, especially if they're confronting their own people for the racism they're doing. But you know, Pākehā should be dealing with Pākehā. And we should be dealing with Māori. Sometimes, it's just good to be there as a friend.

Changing nature of Māori activism

Paul Meredith: Hopefully that answers Tereora’s questions. What are you-- I won't say you're the older generation. But do you believe there's a difference between when you first got involved in activism through to more recent times.

And we've touched on it a bit. But just the changing nature of activism and Māori activism in New Zealand. What do you think?

Annette Sykes: Well, Māori activism has gone through its highs and lows. I mean, I thought it was waning. And then the next minute, we had emerge the occupation in Auckland and then the big dramas around the Fletcher Challenge development up there for Pania and her whānau.

So I think we're issue-focused. But we get distracted by Pākehā politics too, myself included. We get co-opted all the time, whether it's to go and try and change within the system or go and be an advisor on someone else's board and feeling like you're more of a kaupapa than what you actually doing.

You want to actually be on the road with Tina with the Tino Rangatiratanga flag saying, don't come in here. We've got to save our communities. Those are the temptations. And then having real frank discussions with people that pull you back and say, what are you doing there? Is that just about making money, making you feel good, making you visible? Or is that about effecting real change?

What are the personal outcomes of activism

Paul Meredith: Yeah, what have been some of the personal outcomes for you both?

Annette Sykes: Well, I've got two beautiful children out of activism. I love it. Nothing more or less than that, mate.

And they're different than me. But they share the same values as me. So I couldn't have wished for a better outcome.

Paul Meredith: What about you, Tina?

Tina Ngata: I guess for me, the approach that I developed over time to activism was really what helped speed me home. I was always intending to come home. But I realised that in order for me to be able to-- And this is my own approach to it.

In order for me to be able to hold any kind of ground or make any kind of stand, I needed to understand my whenua what my whenua felt like to stand on and to look after as well. And I needed to be in service to my hapū and work in service to my hapū in order to have a strength of how I stood in the face of other larger issues as well. So Yeah, it's helped to speed my return home to live on our whenua and work first and foremost with my hapū and have that inform my lens in the world.

What approach would you suggest to address institutional racism in the public service?

Paul Meredith: OK, got a question from Albert here. What approach would you suggest to address institutional racism in the public service? Who wants it?

Tina Ngāta: I mean, policy. And this is one of the things we need to be very clear about is that racism, the context for interpersonal racism, and when we understand racism today, usually, still, after years and years of work, still, we largely understand racism is what one person says or does to another as an interpersonal, as an interpersonal interaction.

But racism, that context for that person to say that, that context for a decision that's made between two people, whether it's to do with whether you get employed or whether or not you get given a house or you're successful in a tenancy or any of these kind of interpersonal experiences of racism, a context is set for that through policy. And the policy is created in government.

And this is why the government needs to go through-- it's so important for our government to go through its own decolonisation process. This is why constitutional transformation is so important. Because until we unpick the inherent white supremacist, imperialist roots of our own government and the policies that it's only ever going to produce because it's never addressed that. Until we do that, we're going to still keep on setting a social context for institutionalised racism in Aotearoa.

Annette Sykes: Demanding a Māori space in your workplace so that Māori have places for themselves. And recognising every time you want to learn Te Reo on your harassing your co-workers, you're taking your co-workers from some time for their own nurturing. So that's one of the things that worries me. I get demands from a whole lot of Pākehā lawyers to try and say, can you teach me what the latest thing and Tikanga Māori is?

Well, hello, I'd like to just spend some time focusing on developing tikanga Māori so that we've got a better platform after 170 years of invisibility for the next generation. The other thing is making sure that there are bicultural processes in place encouraging re reo me ōna tikanga in the workplace and don't get frustrated when you have a karakia and you have someone like you Paul, hi te whakapākehā ōna whakaaro. You've just got to be more tolerant.

And I think they've made some changes. Tina might have been the advisor on it. But I've seen the state sector acts got some pretty good changes and making them hold them to account those policy changes. Get your unions involved and say, hey, this is an Act now. What does that mean for the workplace?

We have to give effect to Te Tiriti and the way we operate. What does that mean?

Where do you think we're at?

Paul Meredith: I mean, where do you think we're at? This will be the final question. Where do you think we're at? I'm thinking '80, was it '86, in the '80s, we had Puao-te-ata-tu, and it talked about institutional racism.

We've now got the State Sector Act acknowledging the Treaty. Where do you think we're at? What's your hopes for the future?

Annette Sykes: I still think it's window dressing at the moment. I think what's going to be a steep change is the teaching of our history in schools. So I think Section 4 of the Education and Training Act and its implementation is going to be fundamental in the transformation of the next generation.

And I've already seen on this stream here a number of young men and women who are would gladly march behind.

Step up. Take the leadership. You already are. But I'm sick of being in the front. But if I'm going to need to be in the front, I think we've got a good-- I think we've nurtured a good generation of intellectuals and activists.

The next thing is, how do we focus that to achieve real change? By 2040, I still want to separate Māori justice system in place. I still want cogovernance where we require it.

I want my Māori governance where it's fundamental. I don't want our people living in caravans. I don't want my cousins not having work or their work being undervalued because it's mahi marae..

Where are we at? We're certainly a hell of a lot better than where we've been. But as James Henare said, we've got much further to go. We've come too far to not to go further. And that's the challenge for us.

I think some people put a stake in the ground and said, we're here. Colonisation's gone away. It's forever the present as Tina's presentation highlighted.

Paul Meredith: I think you have to finish your book Tina? hei tohutohu i ngā uri whakatipu? Tina? He kupu whakamutunga?.

Tina Ngata: I think-- everything that Annette said I agree. I think it's really incredible and inspirational to think about-- I mean, I was born in 1975. And when I think about, that was a pretty big year in terms of acts and the formation of different things here in te Ao Māori. And when I think about what's been achieved in terms of our radio stations and television stations, our reo , the Māori economy and all of these things, it's pretty amazing what we've been able to achieve over my lifetime so far.

And that gives me great hope for where we are headed. That said, I think we are really at a cusp of some great change at the moment. And we do have to hold the line, now more than ever. We have to hold the line. And we have to be clear about the direction that we're heading in.

There's a saying. I don't know. It was, just one of our Indigenous sisters had said to me one time. You know, Tina, the most dangerous time in any abusive relationship is that moment when your abuser realises that you're close to leaving.

And we are very close to leaving. And that makes our abuser very violent. And it makes it a very dangerous space as well right now.

So we have to hold the line. We have to be true to where it is that we're headed. And we have to be uncompromising in our pursuit of constitutional justice for Indigenous peoples and for Aotearoa especially. Yeah.

Paul Meredith: Ka pai, no reira tēnei rā te mihi atu ki a kōrua ki ō kōrua rangatira me pēwhea rātou. Ki a tātou katoa e huihui mai nei. Mea mai taku tipuna a Rewi.

Me whawhai tonu mātou ake, ake tonu e.

Tina Ngata: Ngā mihi nui

Annette Sykes: Tēnā koe

Paul Meredith: Tēnā kōrua

Any errors with the transcript, let us know and we will fix them email us at digital-services@dia.govt.nz

Pursuing justice for Māori

Māori rights defenders have shaped Aotearoa New Zealand in the past with campaigns taking many forms. Hear prominent Māori rights defenders Annette Sykes and Tina Ngata discuss what recent threats have rallied acts of resistance.

Join us as Annette and Tina share their personal involvements in the pursuit of justice for Māori, while recounting what justice campaigns look and feel like at the coalface, and what some of the responses or outcomes have been.

Register for a link to join this talk

This event will be delivered using Zoom. You do not need to install the software in order to attend, you can opt to run zoom from your browser.

Register if you’d like to join this talk and we'll send you the link to use on the day.

About the speakers

Annette Sykes (Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Mākino, Ngāti Awa, Tūhoe) is an activist and human rights lawyer specialising in the rights of indigenous peoples to promote their own systems of law. A strong focus in her career is on all aspects of law as they affect Māori especially constitutional change. She has her own law practice in Rotorua.

Tina Ngata (Ngāti Porou) is a mother of two from the East Coast. Her work involves advocacy for environmental, indigenous and human rights. This includes local, national and international initiatives that highlight the role of settler colonialism in issues such as climate change and waste pollution, and promote indigenous conservation as best practice for a globally sustainable future.

Check before you come

Due to COVID-19 some of our events can be cancelled or postponed at very short notice. Please check the website for updated information about individual events before you come.

For more general information about National Library services and exhibitions have look at our COVID-19 page.

Endeavour protest, Tūranga 2019. Photo by Dylan Owen.