Truth and the war

The catastrophe at the Somme

The first day of July 1916 is remembered a hundred years later as the worst day in British military history. The newspapers on Papers Past reveal a different story, which is how it was reported in England and here in New Zealand.

The Battle of the Somme has been much written about this year of the 100th anniversary. For the people of 1916 whose husbands, sons and brothers were in France and Flanders the scale of the tragedy that day would have been almost beyond comprehension if they had known. But they did not know because the authorities made sure they did not know.

It was on the morning of 1 July 1916 that some 120,000 British troops attacked the German lines in a move intended to take some pressure off the French at Verdun. Nearly 60,000 were killed or wounded on that first day, destroyed by German machine guns and by mortar fire.

The figures vary a little, one source giving the number of dead precisely as 19,240, with a further 40,000 wounded, missing or taken prisoner, so a more general figure of 60,000 British casualties in one day is usually given by those writing about the battle. The slaughter was the equivalent of the country’s fourth largest city, Dunedin (population 55,290) being wiped out in a single day.

The men of the New Zealand Division were not involved in this, the first stage of a battle that would last for five months. Their turn would come in September when just over 2,000 New Zealanders would die in the British Army’s fruitless attempts to gain more ground and destroy the German forces.

From the outbreak of war the authorities and the military had introduced strict censorship in the reporting of the war. It is interesting to see just how such an enormous military disaster, in the middle of a global war with no end in sight, was reported in the British press and the New Zealand newspapers.

When war comes the first casualty is truth

-Hiram Johnson, US Senator, 1917

Looking the other way

The correspondents covering the war for their newspapers must have wanted to report positively about the progress of the battle, but they would have had difficulty in writing a report that would pass the military censors: one can see how they would have been reduced to offering their readers half truths or outright lies.

A journalist from England’s Daily Chronicle, for example, who must have been looking the other way all day, wrote "The British launched a vigorous attack after a terrific bombardment of 90 minutes," and added "Our casualties were not heavy," which in view of the casualties sustained, was a deliberate lie akin to calling black white.

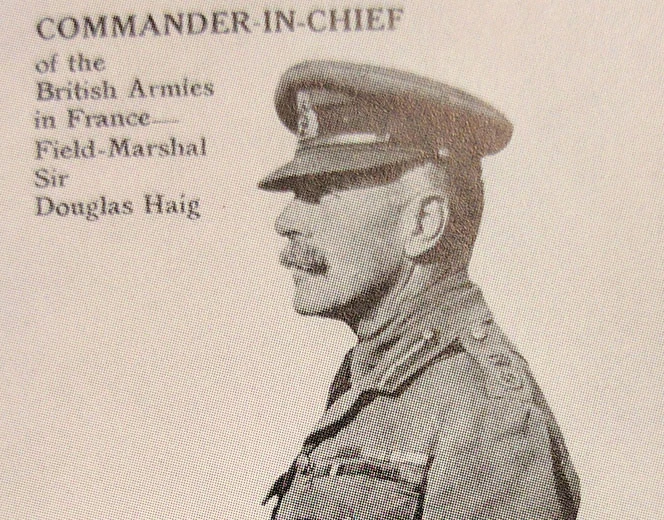

General Sir Douglas Haig, overall commander of the British forces, wrote in his diary that evening about the large number of enemy dead: "which indicated that the casualties were very severe". He didn’t write "our casualties" for these were so much greater than the German losses of 8,000; a large enough loss for one day but just a fraction of the British losses. It was as if Haig was censuring himself in his diary.

At a safe distance in a French chateau ten miles behind the front line, he was hampered by an early lack of information about the progress of the battle along a 25 mile front, and was writing what he wanted to believe was the outcome of the morning’s merciless attack on German trenches from which machine guns mowed down row after row of British soldiers walking across No Man’s Land at a steady 100 yards per minute. However, on the second day of the battle Haig received from his staff an estimate of 40,000 British casualties the previous day (the actual figure was nearer to 60,000). He wrote "This could not be considered severe in view of the numbers engaged and the length of the front attacked." In time Haig would view the battle as a success when measured in terms of British casualties rather than the small amount of ground gained and the villages captured.

"40,000 casualties 'could not be considered severe'." Sir Douglas Haig on a contemporary postcard. Reproduced in Andrew Macdonald, On my way to the Somme: New Zealanders and the bloody offensive of 1916, 2005. Auckland, Harper Collins.

Two newspapers can show how the news of this military disaster was relayed to the population of New Zealand: Wellington's Evening Post and the Otago Daily Times of Dunedin. The Post was the capital’s leading newspaper and was not aligned with any political faction, so is probably a reasonable choice to represent the other newspapers, mostly conservative in nature. The Otago Daily Times, the country’s oldest daily newspaper, represents a South Island view.

All New Zealand newspapers received reports on the progress of the war via cable and telegraph from England. None reported truthfully what was happening on the Western Front and probably wouldn’t have done so even if they had been able to.

Deliberate lies

Historian and journalist Phillip Knightley described this time in his book on the history of censorship in wars since the Crimea:

More deliberate lies were told than in any other period of history and the whole apparatus of the State went into action to supress the truth.

Sometimes the truth of what was happening in the war was supressed almost out of existence when it was too inconvenient for public consumption: An example of this was the losses by sustained by France in the Battle of the Frontiers in the early stages of the war. There were some 300,000 casualties (nearly 25% of the combatants) but this battle was not even mentioned in the British press until years after the war had ended in 1918.

One can understand the need for some censorship in times of war, and in England and in New Zealand the apparatus of military censorship came into force as soon as war was declared. But as the war dragged on with no prospect of victory the need for more vigorous censorship grew so that a dispirited public would not lose heart and demand an end to the conflict.

So the reports were enthusiastic in their spin: "Our infantry inflicted important losses on the enemy, who was compelled to fly back in disorder", reported the High Commissioner in London as quoted in the Evening Post of 3 July. It was reported that large numbers of prisoners were taken but as usual there was no mention of British casualties.

Reports in the Otago Daily Times were just as positive:

At last. The big Anglo-French offensive had begun along a 25 mile front and villages had been taken and over five thousand prisoners.

Sir Douglas Haig’s daily report was headlined "Lengths of trenches taken, fortified villages occupied and numerous prisoners taken." This was at best a partial truth, more a misleading lie, for by the end of the day much of the ground gained had been lost.

British troops fix bayonets before 7.30 am on 1st July, 1916. Still from the film The Battle of the Somme by Arthur 'Geoffry' Herbert Malins. Reproduced in Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Somme: Into the breach, 2016. Viking.

The chilling effect

The process that controlled these reports had three aspects. The military chiefs encouraged the British correspondents close to the battle to tell their readers partial truths or outright lies. As a result these journalists self-censored the reports they sent to their newspapers back in England. There the stories were censored a third time before being cabled around the world.

Much of the war coverage that appeared in the newspapers was simply propaganda devised back in London. All three groups must have felt that the truth about the battle would have been bad, perhaps disastrous, for morale back home.

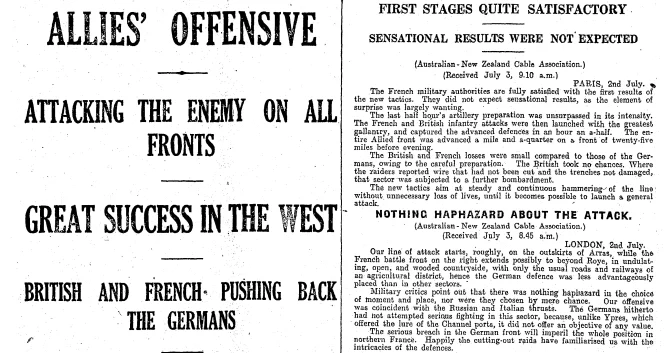

The headlines in the issue of the Post of 3 July (the first day on which the story of the commencement of the battle could be told in New Zealand newspapers) show clearly how the truth had been turned on its head. The reports received via the Australia and New Zealand Cable Association were full of positive captions: "Great success in the West", "The enemy bewildered", "Enemy falls back in disorder" are examples of the wishful thinking that permeated the first day’s reports.

Yet it seems that from early on the ground was being prepared for some small acknowledgment of the truth. The British and French offensive had been "launched in brilliant fashion", so the newspapers said, and there was "nothing haphazard about the attack" and "the first stages were]quite satisfactory".

This reads like a planned justification to be offered to counter the criticism that would inevitably come about the disastrous first day’s attack. Quite how 60,000 casualties could be thought ‘quite satisfactory’ is hard to comprehend, and one wonders if those who wrote these untruths felt any qualms about the extent of their lies.

Headlines reporting on the Somme, Evening Post, 3 July 1916.

One surprising aspect of the coverage in both the Post and the ODT was that small amounts of space were given to German reports on the battle. No doubt those reports were just as misleading, but they seemed a little more forthcoming than those in the Allied press.

German reports gave more detail:

The attacks by the British were preceded by intense fire, a gas attack, and mine explosion... numerous French inhabitants were killed and wounded.

Or:

Enemy aerial attacks at Lille did no military damage, but many civilians were killed.

These reports were no doubt branded as propaganda, but must have been of concern to readers back in England who had little knowledge of the violence on both sides.

A rose-tinted representation

The people back in England, and here in New Zealand, would have believed most of what they read in the newspapers because they had no alternative sources of information other than those soldiers’ letters which made it through the censoring process.

The newspapers of the war years dominated the channels of public information as never before: as K S Inglis, an Australian newspaper historian put it, "their roseate representation of the war, their impression of imminent victory, their suppression or minimization of the losses, defeats, squalor, misery and horror", must have influenced the public greatly. (Quoted by Redmer Yska in ‘The First World War and Truth’ in Ferrall & Ricketts, How we remember: New Zealanders and The First World War, Wellington, 2014.)

The war was to last more than two more years. One wonders if it would have been much shorter if the truth about battles like the Somme had been truly reported and losses like the 60,000 on the first day had been known to the public who expected the newspapers of the time to report the truth about the war.

Hullo Peter, I believe you knew my father at the Harbour Board, Buff Fellows. If I have the right man you may be able to help me. I understand my father spent time relating his oral history to someone. I'd love to track it down.

Thanks

Geoff